Forty-two short films were selected as part of the Toronto International Film Festivals 2014 iteration of Short Cuts Canada. Showcasing a slew of up-and-coming talent residing within the titular nation, each block exposes you to animated, documentary, and fiction work with faces familiar and new. Who knows, a future year’s festival may end up screening a feature from one of these writers/directors that you can say you saw greatness in way back when.

Programme 1

Premiering Friday, September 5th at 9:15pm | TIFF Bell Lightbox Cinema 2

• An Apartment, dir. Sarah Galea-Davis, 17 min.

• Around is Around, dir. Norman McLaren, 7 min.

• CODA, dir. Denis Poulin, Martine Époque, 11 min.

• A Delusion of Grandeur, dir. Vincent Biron, 14 min.

• Mynarski Death Plummet, dir. Matthew Rankin, 8 min.

Pilot Officer Andrew Mynarski is a bit of a legend in his hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba and it would appear his country of Canada as well. The last World War II airman recipient of the Victorian Cross—the British and Commonwealth forces’ most prestigious award for bravery—this hero valiantly attempted to save the life of fellow soldier Pat Brophy before succumbing to the flames of their crashing aircraft. Brophy would survive the ordeal and eventually relay the story of Mynarski’s selflessness, cementing a legacy of numerous honors donning his name such as a Junior High School where he was born, an Avro Lancaster in Hamilton, Ontario, and a bronze statue at RAF Middleton St. George. Now, seventy years after his death, Matthew Rankin commemorates the event with an electric avant-garde short. Entitled Mynarski Death Plummet, what begins as homage to old silent newsreel footage of the war quickly pulsates into a strobe of crude white lines before centering on the ill-fated hero seated in his plane’s gun turret. Utilizing live actors (Alek Rzeszowski plays Mynarski), stop-motion, painting, and celluloid destruction, Rankin delivers a Stan Brakhage-like memorial that cuts to the discharge of bullets and Patrick Keenan‘s bombastic score. We watch in fast-paced collage every last soul on the plane grab his parachute and jump, leaving Mynarski at the door. Glimpsing another pack labeled Brophy, he simply couldn’t descend without first finding his brother at arms—no matter the cost. Silent film aesthetics ratchet up the melodrama until meticulously rendered, colorful scratched animations takeover like fireworks in the sky. The result is an invigorating piece that captures both the subject matter’s severity and its capacity to be told as more than another sullen piece of history. Mynarski already has the usual posthumous honors: the stuffy rank and file medals along with government-sanctioned locations housing his name. So it’s a delight to watch a unique piece like this turn his heroism into a work of art that’s able to educate those in the dark without merely directing them to a book of canned, impersonal entries. Mynarski Death Plummet has life and character, immortalizing this event with kinetic energy and tactful humor. If only more tributes could shed the conservative need for solemnity and replace it with celebration. An acid bath of perfectly placed crackling swirls on film is just as good as reenacted flames on set. B |

• Sleeping Giant, dir. Andrew Cividino, 16 min.

• Zero Recognition, dir. Ben Lewis, 10 min.

Programme 2

Premiering Saturday, September 6th at 10:00pm | TIFF Bell Lightbox Cinema 3

• Bison, dir. Kevan Funk, 14 min.

• CHAINREACTION, dir. Dana Gingras, 12 min.

• Liompa, dir. Elizabeth Lazebnik, 16 min.

Adapted from the 1928 short story by Yuri Olesha, Elizabeth Lazebnik‘s Liompa gives us a glimpse at the differing stages of life. We may only hear from the dying Ponomarev (Aleksey Serebryakov) as he refuses to cope with the fact he’s lost all control over the world around him, but there are also two more characters one could see as stepping stones of evolution still caught in the hold of reality’s grip. Alexander (Stepan Serebryakov)—for example—has just come of the age where doing and creating are all he can see. He wants to give names to everything around him so as to know them while Ponomarev hopes to forget all labels in his mind and wish to once more experience them unencumbered by man-made convention: fresh, wondrous, and new like a newborn. The short is therefore a philosophically cinematic interpretation of René Magritte‘s Ceci n’est pas une pipe. It begs us to ask what life is: the world itself available to us if we’re willing to meet it, the limitless possibilities of transformation into whatever our imaginations conjure, or the encyclopedic notion of understanding above seeing. For each of these characters—the “newborn” being a young wide-eyed boy roaming the house with unfiltered glee at things possessing nuanced meaning that his innocent mind is unaware of comprehending (Sasha Romanov)—one’s idea of life is another’s undoing. The boy seeks fun, Alexander strives for meaning, and Ponomarev simply wants experience in a circle of life folding back onto itself with desire always peering forward until progress loops back to the beginning. Shot with a stillness that allows every tiny noise from the scrap of wood, the chopping of an onion, or the cough of a sick man to roar with energy, Liompa becomes a catalog itself hovering on seemingly innocuous items that mean the world to some. A piece of wood is simultaneously a noise-making toy, a building block of technology, and a concept that doesn’t exist unless in our hands. Everything Lazebnik lingers on has a visceral, physical, and emotional charge we alternatingly embrace and abhor as we grow nearer to our oblivion. In the end all we know and see survives inside us and us alone. Their intrinsic meanings gradually disappear as our ability to understand dissipates until we’re left only with memory. Memories of life we no longer have, soon evaporated to make room for future generations to create their own. A- |

• The Sands, dir. Marie-Ève Juste, 21 min.

• Take Me, dir. André Turpin, Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette, 10 min.

Short film collaborators Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette and André Turpin-this is their third work as a duo-focus Prends-moi [Take Me] on a job very few are fit to complete. I’ve volunteered with handicapped people as a bowling scorekeeper and have seen a wide variety of group home workers come and go with differing levels of compassion and care towards those in their ward. For every companion sitting down on the lane to watch, cheer on, and engage there were three roaming around on their phones as though it was break time until the game completed. To most it is a thankless job and you cannot necessarily blame many for not quite cutting it. But to others the act of caring for a less fortunate soul is a gift of grace in itself. While they and I lent support, facilitated safety, and helped the athletes have fun, Barbeau-Lavalette and Turpin’s sights turn towards a much different and more specific aspect of providing the infirm the opportunity to partake in what we unencumbered take for granted. At the beginning, Sami the aid (Sami Soleymanlou) accepts his job with a clinical detachment devoid of issue. We watch him bring a nameless young man (Alexandre Vallerand) physically unable to walk or truly maneuver his body into a clean bed. He places him gently, removes his underwear, and pushes the mattress towards another off-screen revealed to contain the young man’s wife (Maxime D. Pomerleau) awaiting him with a smile. This is the intimacy room and Sami treats assisting them in their endeavor as he would another patient in need of lunch. But it isn’t truly the same and this particular instance is uncomfortably unorthodox to complete without questioning his boss. On the surface he’s asked to do something totally unaligned with society’s “normal” thought process towards intimacy due to it being the only way these two lovers can satisfy their carnal desire. We can’t help but sympathize with Sami’s plight and wonder what we’d do in the same situation. While you might say he puts himself into a position for this situation to arise, it’s not like he’d ever think he’d have to go as far as he’s asked in the film. In the end, though, someone willing to provide all things humans need to survive can’t easily ignore physical interaction’s place in the equation. It’s amazing how powerful a simple “thank you” can be towards making it justifiably pure and immeasurably empathetic. B+ |

Programme 3

Premiering Sunday, September 7th at 9:45pm | Scotiabank Theatre 14

• Chamber Drama, dir. Jeffrey Zablotny, 11 min.

• Father, dir. Jordan Tannahill, 10 min.

• Hole, dir. Martin Edralin, 15 min.

• Indigo, dir. Amanda Strong, 9 min.

• Light, dir. Yassmina Karajah, 13 min.

• Luk’Luk’I: Mother, dir. Wayne Wapeemukwa, 19 min.

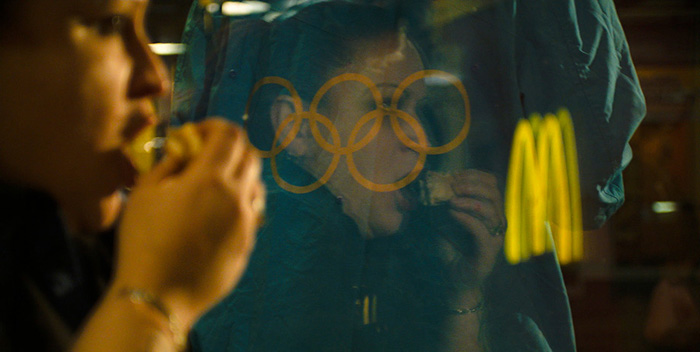

I’m lost and it’s not a feeling I want to have when the TIFF Short Cuts Canada programmer calls Wayne Wapeemukwa‘s debut short Luk’Luk’I: Mother “narratively sophisticated”. That’s a description that will either boost your ego when the work speaks to you clearly or demoralize your intellect when you find comprehension is completely absent. Those words are doing the latter for me now as I unsuccessfully try to reconcile the synopsis with what I saw. Just the idea that a “full-time mother and part-time sex worker goes missing on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside during the 2010 Winter Olympics” has me scratching my head because if Stoney (Angel Gates) ever went missing, it wasn’t until the moment before the end credits began to roll. My best guess is that the film portrays the moments before this likely real-life event. If that’s the case, maybe it will have an amazing emotional worth to viewers aware of what happened. I’m not one of those people and being ignorant to the situation confuses me because I never felt Stoney was anywhere she didn’t want to be until that final second. Instead I saw it as a day in the life piece following her travels; cross-cutting in her daughter Star (Lilianna Lagreca) playing with her grandmother (the credits say it’s the girl’s foster mother but I didn’t get that at all); and sharing a glimpse of Eric (Eric Buurman). He’s interesting because he may be playing himself considering he breaks the fourth wall to ask the director what to do next—a singular moment of fabrication starkly contrasting the rest. The title Luk’Luk’I is Squamish for “Grove of Sacred Trees”, a place located in Crab Park, Vancouver. I’ll infer this is where the woman who went missing disappeared as her city celebrated Ice Hockey gold. Rather than truly describe that incident, however, the film shows us surreal musical interludes that play more as isolated vignettes than pieces of a coherent whole. We watch Gates take a shower in slomotion, witness Buurman singing karaoke, and later examine his complete process for shooting heroin with the gold-winning goal being scored the instant he presses his syringe’s plunger down. It’s therefore a powerful piece on poverty, drug addiction, and the lengths parents go to support their children, but I feel there’s more I cannot see as an outsider. I guess I’m simply not one of its specific commentary’s targeted viewers. C- |

Programme 4

Premiering Monday, September 8th at 6:15pm | Scotiabank Theatre 14

• Broken Face, dir. Alain Fournier, 16 min.

• Entangled, dir. Tony Elliott, 15 min.

Anyone willing to dive down the rabbit hole of quantum entanglement to exist in two places simultaneously is doing so for a reason. You may delude yourself into believing its for science or the simple fact of proving it can be done, but there’s a personal secret hiding beneath any ideas of social application. Why else wouldn’t the experimenter let his girlfriend in on the challenge? Why would he (Aaron Abrams‘ Malcolm) allow her (Christine Horne‘s Erin) to witness the incoherent, institutionalized ramblings of a brain-dead boyfriend in the aftermath without explanation? You cannot therefore blame her for doing all she can to discover the truth in an attempt to make him whole again. In a year full of great science fiction, Orphan Black scribe Tony Elliott‘s short film Entangled is yet another worthwhile addition. Dealing more with the ramifications of such an invention—a laser that can sever you into two identical beings coexisting miles away from the other—than the technology itself, the film becomes a hubristic document of one man’s efforts to conceal being the exact cause of his exposure. But even at Malcolm’s worst, love prevails in bittersweet tragedy. Both he and Erin discover how the strain of being in two places at once is too much to bear and they look at their life together before making the sacrificial decision to rip off the Band-Aid and end their suffering. Abrams and Horne give emotively captivating performances as layers are revealed to show the flawed and very human reasoning for their characters’ predicament. We watch her Erin and their colleague Cameron (Joey Klein) rush headfirst into the path of this laser as Elliott splits his screen in a burst of light. Showing her simultaneously in the basement of Malcolm’s laboratory and an unknown barn is invigorating; the steps necessary to prove what’s happened concisely lain out so we can focus on the inevitable confrontation with their not so vegetative patient. Whether you read it at face value as the brain’s inability to sustain two concurrent lives or a metaphor for a liar’s conscience sabotaging his deception, Entangled is a delightfully inventive gem. A- |

• Sahar, dir. Alexander Farah, 14 min.

• A Tomb with a View, dir. Ryan J. Noth, 7 min.

• What Doesn’t Kill You, dir. Rob Grant, 12 min.

Programme 5

Premiering Wednesday, September 10th at 9:30pm | TIFF Bell Lightbox Cinema 2

• Day 40, dir. Sol Friedman, 6 min.

Who doesn’t like a little revisionist history? Especially when it concerns the sanctity of the Bible—I think that’s my favorite kind. Because why did that book become this whole end-all/be-all document of our existence, morality, sin, and promise? Who the hell were Peter, Paul, and Mary besides 1960s folk singers with some kick-ass songs? Why can’t director Sol Friedman and writer Evan Morgan‘s voices be just as important when it comes to describing how we humans came to be? The answer is: they can. And thankfully for us they will while also having fun in the process. When you think about it, a story like Noah and his ark is pretty crazy—a children’s book notion of mankind’s capacity for purity to inspire and God’s vengeful wrath to frighten. Centuries from now when science allows us to become Gods ourselves, who’s going to really care about having a dude like Noah be seen as a hero? As a self-proclaimed vessel hearing the word of God, wouldn’t it make more sense that he would be a few screws light of a full deck? That’s the kind of guy a ship full of animals could really mess up if given the opportunity. Enter Freidman and Morgan’s hilariously subversive Day 40, a tale of Noah’s Ark to end all versions ever told. It has all the trappings of a fun Disney cartoon with anthropomorphized animals and—no that’s about it. Crudely animated in stark black and white lines, this R-rated account is purely the result of 21st century irreverence with a welcome desire to poke fun at cherished faith-based fact for the fantastical nonsense it is on paper. With a left-face turn of events ending the journey—how it goes from the animals’ horror movie-esque discovery on land to our existence at present is anyone’s guess—we find ourselves hoping new takes on other Biblical yarns will follow. B+ |

• The Encounter, dir. Frieda Luk, 10 min.

• Intruders, dir. Santiago Menghini, 9 min.

• Last Night, dir. Arlen Konopaki, 6 min.

Sometimes you have to wonder where an artist’s head was when coming up with the idea for their latest work. I can see Arlen Konopaki and Christian Capozzoli giggling over a couple beers about how funny it would be if two roommates were engaged in a debate about whether one masturbated on the face of the other while he was sleeping the night before. It’s kind of a brilliant conceit when you think about it too because the situation is so absurd that no one would really question the filmmakers’ decision to escalate their victim’s means of proving the trickster was culpable to an extremely nonsensical level. And honestly, if you were warped enough to cum on your friend’s face, why wouldn’t you still deny it when caught red-handed? This is the rapid-fire comedy short Last Night. Taking place almost entirely on a living room couch—with the occasional visit to the bedroom in question in order to display the facts—the duo masterfully traverse their argument with straight faces. I mean Arlen isn’t even really that mad the incident happened as long as Christian finally cops to it. Think an argument you had with whomever you live/lived with about whether or not he/she left a glass of water on the coffee table without a coaster. It’s the stupidest thing to argue about and yet it happens with the utmost severity to simply assert your inflated sense of superiority. Now switch the glass of water to a semen-filled penis and the table to your face and let the laughter commence. B |

• Still, dir. Slater Jewell-Kemker, 16 min.

Programme 6

Premiering Thursday, September 11th at 6:15pm | Scotiabank Theatre 3

• The Barnhouse, dir. Caroline Mailloux, 19 min.

• Burnt Grass, dir. Ray Wong, 11 min.

• Fire, dir. Raha Shirazi, 12 min.

• Godhead, dir. Connor Gaston, 11 min.

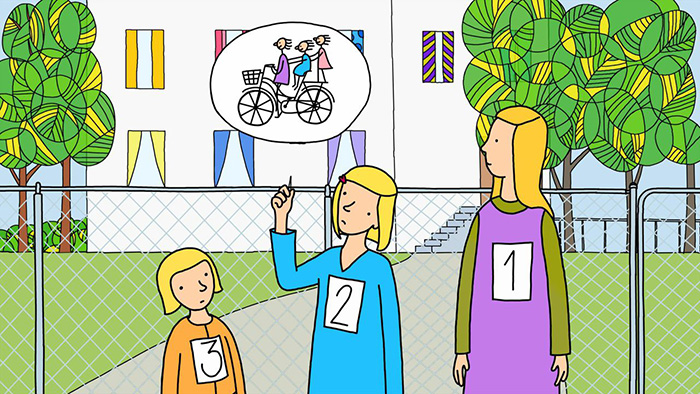

• Me and My Moulton, dir. Torill Kove, 14 min.

An Oscar-winner for Best Animated Short in 2007 with The Danish Poet and nominated in 2000 for My Grandmother Ironed the King’s Shirts, writer/director Torill Kove returns to the medium with Me and My Moulton. It’s a brightly colored line drawing cartoon about a young girl and her family in Norway during the spring of 1967 that deals with themes of envy, embarrassment, and empathy to make it relatable for children and adults alike. We all go through phases of wanting to be just like everyone else and conversely completely original at some point in our lives. And whichever we hope to accomplish usually finds opposition—intentionally or not—very close to home. For the seven-year old girl at the film’s center, those preventing her from being a “regular” kid in a “regular” family are her parents. She sees her best friend’s life in the apartment below her with a mother who stays home and makes snacks and a father who does yard work without a shirt before heading to military training as ideal. Her own mom and dad’s careers as contemporary architects make them stick out like sore thumbs instead. So she yearns for a generic living to escape from constantly being the people in their neighborhood that everyone knows and her solution—along with sisters aged five and seven—is to ask for a bike to both fit in and get away whenever necessary. Her parents obviously find a way to ruin those plans. Rather than be a brat about it, however, the girl finds understanding and thanks. She improvises joy after realizing the perfection she believed in may not have been as perfect as what she has. Kove therefore injects some nice children’s book morality to the proceedings amidst humor (a three-legged chair gag is great) and artistry (I loved the translucency of the tree leaves to denote their lack of opaqueness even as a whole). The aesthetic is very much two-dimensional Flash animation-esque, but the content helps render any unfair thoughts about it not being Pixar-quality moot. There is a charm to the look that recalls stories from my own childhood—the simplicity of quality many forget in lieu of life-like animated spectacle. B |

• The Underground, dir. Michelle Latimer, 13 min.