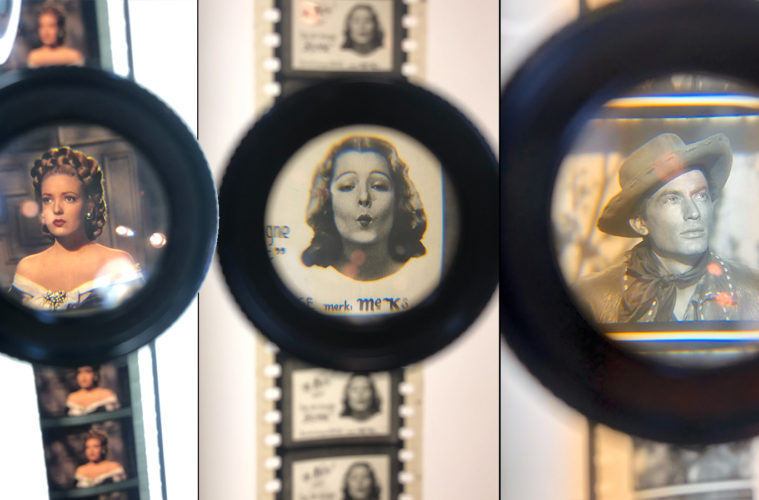

Nitrate prints available for viewing, including Linda Darnell in Forever Amber, a Russian cologne ad, and Gregory Peck’s camera test for Duel in the Sun.

It’s been nearly 70 years since Kodak manufactured their last nitrate film, but the appreciation for the highly flammable, stunningly vivid film stock lives on in more ways than one in Rochester, New York. The George Eastman Museum, home of photography and moving image collections, opened in 1949 and two years later in 1951, the 500-seat Dryden Theatre was unveiled. However, it wasn’t until 1996 that the museum’s nitrate collection found a more secure home. Located in North Chili, NY–about a 15-minute drive from the museum–the unassumingly adorned Louis B. Mayer Conservation Center is a safe haven for nitrate film stock.

With room for 40,000 reels of film (about 26 million-plus feet) amongst its 12 vaults–completely separated to prevent a total catastrophe if a fire breaks out in a single vault–the center houses some of the most precious gems in film history. While taking a tour, I was able to hold reels of the original camera negatives of Gone with the Wind and Wizard of Oz, as well as an early Lumière short and the infamous Judy Garland test shoots for Annie Get Your Gun.

Also the home of restorations of Stanley Kubrick’s Fear and Desire and Orson Welles’s Too Much Johnson, as well as the silent films of Cecil B. DeMille and Georges Méliès, it’s only a miniscule sample of what’s behind the vaults, which contain about 55% of Warner Brothers-owned films, much of which are currently undergoing inspection as the company prepares its own streaming service.

While the museum is dedicated to the art and craft of preservation year-round, even launching The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation in 1996, which has over 240 graduates to its name, the Dryden Theatre is one of the few in the world equipped to show these 35mm nitrate prints.

But it’s only more recently–in 2015–that they found an occasion to share both the nitrate prints they store and those from around the world with The Nitrate Picture Show. Now in its fifth edition, the film festival of rarities brings in people from around the world, from a Rochester native like myself all the way to an attendee I met that flew in from western Australia, whose family has been in the film exhibition business for decades.

Taking a Telluride-esque approach of revealing the lineup the morning the festival begins, the excitement of the unknown only further fuels interest leading to nearly sold-out crowds and more concentrated fervor around the annual grand finale: Blind Date with Nitrate. (More on that later.) Founded by Paolo Cherchi Usai and headed by directors Jared Case, Jurij Meden, and Deborah Stoiber, the festival celebrates the craft of cinema and exhibition like no other I’ve previously attended. Each screening begins with a hearty, personal thanks to the projectionists in the booth, receiving a round of applause and, when it came to the marquee screening of Rebecca this year, a standing ovation. Following a carefully considered introduction–which details both the source and status of the nitrate print, as well as essential production tidbits–the curtain raises in a leisurely fashion, as if the treasures to be displayed underneath warrant a moment of ruminative reflection before unspooling.

The curtain raises at Dryden Theatre.

To get a sampling of the luminous quality of the nitrate stock, the festival began once again with a shorts program. Opening with John Ford’s transportive 1942 war documentary Battle of Midway, the tranquil, vivid blue oceans are soon met with destruction and the director captures the siege from both below and above ground in startling clarity. The program also included a few animations: Frank Tashlin’s subversively sexual egg-laying satire Swooner Crooner, Dave Fleischer’s imaginative lark The Cobweb Hotel, Connie Rasinski’s amusing The Temperamental Lion (which was found and sent to the Chicago Film Society and they traveled with it here to see it for the first time), and, presented with most impressive condition of the batch was George Pal’s Puppetoon short, Tulips Shall Grow. The colorful, creative Oscar-animated short, released in 1942, follows a love story between a Dutch boy and girl that turns dire when Nazi-esque evil invades their idyllic garden of love. Also included in the shorts were a trio post-war travelogues: the beautiful testament of resilience, Looking at London; the Norway adventure, Landscape of the Norse; and the underwater Coral Reef adventure, Gardens of the Sea.

Moving to the features, kicking off the evening was Henri Langlois’s print of Luis Buñuel’s L’âge d’or, bought by curator James Card when the Cinémathèque Française founder needed some cash while visiting the United States. The dark humor of the the surrealist, subversive masterpiece, fully appreciated by the audience, gave the film new life, particularly those who may have first screened it in rather drab film school settings. From scenes of lovemaking in the mud to child murder to toe-sucking, it was the ideal bourgeois-bashing way to begin the festivities.

Friday night continued with Preston Sturges’ rip-roaring Technicolor comedy The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend, which opens with a riotous bit of child-rearing before jumping into the madcap hijinks of the sharp-shooting Betty Grable, gloriously shining on nitrate. As her character of Freddie gets further in trouble with the law, Sturges plays the comedy up to high heavens. A gag featuring a goon falling off a roof over and over again after getting shot and another in befuddlement, getting hit in the face with water after each shot, may hint at where a few of David Wain’s They Came Together ideas came from.

Inside the projection booth at George Eastman Museum’s Dryden Theatre.

Saturday began in the bowels of the carnival underbelly with Edmund Goulding’s vicious rise-and-fall story of mentalists and magicians, Nightmare Alley, led by a fierce Tyrone Power. In a print from UCLA Film and Television Archive, Lee Garmes’s marvelously shadowy cinematography seeps into the dark consciousness of the mind as the road to fame bites back. Screening on the heels of the news that Guillermo del Toro would be reimagining the William Lindsay Gresham-penned source text for his next film, one imagines Leonardo DiCaprio back in the psychologically-fueled thrills of Shutter Island with this shadowy noir.

What followed were two rather unfortunately lackluster offerings. With its beautiful, flowery Finnish landscapes and buocolic images of lovers embracing in the gleaming sun, it’s clear why Valentin Vaala’s Ihmiset suviyössä (People in the Summer Night) was selected to play, but the film seems to be in search of a never-found worthy narrative as the dull characters flounder about. Then there was Gordon Douglas’ by-the-numbers Cinecolor western The Nevadan, in which Dorothy Malone’s red scarf juxtaposed against a blue sky provided one of the patchy film’s few moments of splendor. Aside from an entertaining Randolph Scott, the MVP is the town’s sheriff, Dyke Merrick (Charles Kemper), who is simply content being poor amidst the greed-fueled gold rush as he fashions fake teeth for getting into nightly brawls.

The star of the show was Daniel Selznick’s personal print of Alfred Hitchcock’s Best Picture winner Rebecca, which was presented in all its pristine glory transporting the viewer back to 1940. From the opening shots as we track through the forest before seeing the de Winter mansion to the crashing waves hiding a dark secret to the tears of Joan Fontaine as her innocence becomes inadvertently twisted by the ghost of the past, every moment was rendered with new clarity. Since George Eastman Museum also preserves nitrate screen tests of the films, they screened them after the film, showing a humorously uninspired Fontaine in a number of costume tests–including one used for another Selznick production, Gone with the Wind–as well as test featuring two actresses who didn’t get the part: Anne Baxter and Loretta Young, the latter who was, well, simply too young for the role.

The final day kicked off with another noir-fueled descent into madness, courtesy of John Cromwell’s Humphrey Bogart-led Dead Reckoning, an overstuffed but no less entertaining mystery. Recently discussed as one of Bogie’s overlooked films on our podcast, The B-Side, Hollywood’s preeminent movie star is in top form here, sprinkling pulpy barbs across the deliciously convoluted voice-over and numerous sultry exchanges with Lizabeth Scott.

Nightmare Alley

The penultimate screening was William Wyler’s adaptation of the Broadway play, Counsellor at Law, which is wholly set inside the revolving door of the law practice of Simon (John Barrymore) & Tedesco (Onslow Stevens). Elmer Rice’s chatty screenplay weaves together intriguing examinations of social status as Simon sheds his lower-class Jewish upbringing for the riches that the highest level of legal practitioning brings, and those he’s left behind are not afraid to confront him about his change. Burdened by the unceasing demands of his clientele and a scandal that could find him disbarred, the drama is most poignant when it slows down. In a chilling climax well-executed by Wyler, Barrymore’s Simon peers out over the streets below Empire State Building, contemplating suicide.

A tinge of excitement and sadness swept through the Dryden as it was time for the festival to come to an end with a Blind Date with Nitrate. Judging from the widespread gasps and cheers when “A Production of The Archers” appeared after the curtain rose, the surprise was clearly well-kept and thoroughly embraced. If there were ever directors whose work was born to play on nitrate, it is certainly the vibrant films of Powell and Pressburger, whose beloved The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus played in past years. This year they dug deeper into the archives to present their fantasy melodrama Gone to Earth in its original U.K. edition, rather than the heavily re-cut U.S. version titled The Wild Heart. Starring a radiant Jennifer Jones as Hazel Woodus, who believes in the whims of nature to decide the path of her heart, she’s torn between two lovers: the dashing, Gastonian Jack Reddin (David Farrar) and the timid local minister Edward Marston (Cyril Cusack). Shot by Christopher Challis in glorious Technicolor on location in the English countryside, the setting lends a mythic quality to the doomed romance as we see man’s conceited objectification lead to destruction.

As better resolution, more dimensions, higher frame rates, comfier seating, and dinner menus have sidetracked the industry into seeking a more lucrative theatrical experience, the Nitrate Picture Show is a testament to the most transportive time one can have in a cinema–and the process by which these stunning prints see the light of day is dying. If a nitrate film shrinks any more than 1%, it becomes virtually un-projectable. Through the efforts of the George Eastman Museum and the few conservation institutions like it left in the world, vivid pieces of film history are being kept alive. While their annual festival is an invigorating, unforgettable experience for any cinephile–most importantly, it’s a vital reminder to support the preservation of these invaluable relics.

The Nitrate Picture Show will return June 4-7, 2020. Explore more about this year’s program here.