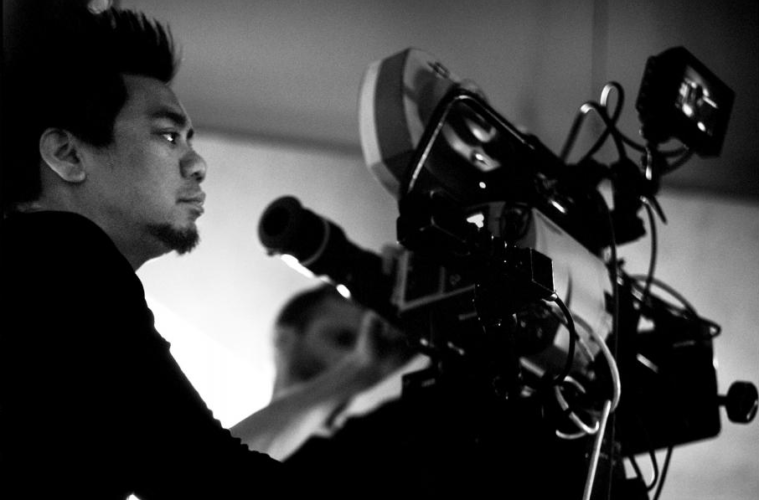

Having had a long career of making good films look great and making bad films look good, Matthew Libatique is one of the best living judges of cinematography. It thus makes sense that the world’s foremost cinematography-oriented festival, Camerimage, would turn him into a recurring figure on their Main Competition jury. While attending the festival, we both sat down for a brief, albeit revealing talk, one mostly centered on his mindset as an influential voice in this specific world — as well as the insecurities that come with the position — and the bonds shared by fellow cinematographers.

You’re on the Main Competition jury. How many times have you done this?

This is my third year here. It’s my second time participating as a juror. The first time I came, Darren [Aronfsky] and I got the Duo Award, which was an honor, but it took me years, actually, to come here. Last year I was here on the Polish jury, and, this year, on the Main Jury.

What’s the sense when you see a festival geared toward cinematography? Do you think it’s overdue, or hoping to see more of?

It’s not recognition so much as it’s a chance to celebrate with your fellow craftsmen, and sort of share stories and see each other. You know, we don’t work with each other. We know each other from ASC awards or festivals or Camerimage. For me, personally, it’s not about recognition, because I think it’s conceited. But I do like the celebration of the craft, which is why I love it and support it so much. But the camaraderie that cinematographers do have is kind of special, so every time I’m here and get to meet Christian Berger or Christopher Doyle or Ed Lachman, it’s a great honor. And then you see the younger generations, and that’s also really satisfying. I don’t know, it’s the world… we’re sharing it not only with people from New York or Los Angeles. We’re sharing it with cinematographers from around the world — which is, I think, probably one of the most special things. It’s kind of a priority for me, now, to come here.

What’s the camaraderie among cinematographers, exactly?

[Laughs] It’s funny, because I went to the American Film Institute, and I think where that school really excels is the cinematography program. That’s when I first started to feel it, but then I thought it’s because we were all students in the same class. And then, as my career went along, I just realized that, everywhere, it stayed the same. There was a celebration of each other’s work and a respect. I think we all sort of recognize how difficult the job is, and we all sort of have a love for filmmaking and consider ourselves filmmakers, first and foremost. I guess that’s what it is, and you just sort of share the… you know, we all have similar complaints and bitch about things. Ed always likes to say, “We can bitch about directors when we get there.” And it’s true. And producers and whatnot. It’s just the way to sort of share technical knowledge. But sometimes I honestly don’t talk technically that much here. It’s about how we sort of live, the sort of gypsy lifestyle that we have to deal with.

I don’t know how much you can say, but do those complaints recur among longtime collaborators — that is, the creative types who know you best?

Of course. You’re not always going to agree 100% with what a director wants to do.

Even if it’s someone you know well.

Even if it’s someone I know well. Ultimately, they’re in charge of that screenplay. If they wrote it or not, they’re the ones being given the task of creating performances that make that film happen, and our ask is to articulate that into an image. So it doesn’t matter: I’ve done five films with Darren Aronofsky now, and I’ll have complaints. It just happens. And he’ll have complaints about me, so I’m sure that, if there’s a directing event, they’re going to complain about the cinematographers! [Laughs]

But there’s nothing new to it. We all kind of share similar stories about not agreeing with something or being put in certain situations where it’s not an ideal for the image. Sometimes we bitch about the schedule or the amount of money or the amount of time we have, but it’s normal frustrations that you have in this occupation, and we all share similar stories. We’ve watched people like Michael Seresin and Film AU. Those guys have amazing stories as well. You know, Michael Seresin shot Angel Heart. To hear a story about that is amazing, and it’s not like you’re prodding anybody to get a story; they pop up in conversation. “Oh, one time when I was on Angel Heart!” or, “Oh, one time when I was on Requiem for a Dream!” It’s kind of beautiful.

Have you seen the conversation around and focus on your profession change over the years? I feel like, nowadays, certain venues — be it Twitter accounts or video essays — shine a light that wasn’t previously present.

Sure. Yeah, of course. You know, on Twitter alone, there are so many people putting together Twitter accounts that are dedicated to the image, which is amazing. I’ll look at Twitter and, all of a sudden, an image pops up from a movie. There are two or three of them; there’s a website called Film Grab. I mean, that didn’t exist when I was in school; Twitter didn’t exist when I was in school. And the rise in digital cameras and DSLRs and the motion pictures being more accessible, and having your laptop and being able to carry basically a filmmaking kit in a backpack has changed the game. I see people all the time who are carrying RED Epics and Dragons in backpacks on the plane. The game has changed, and now there’s more cinematographers, and people are shooting their own stuff and taking it into their own hands because it’s more accessible. So, yeah.

And, consequently, when you’re starting out, because there are so many new cinematographers and so many people interested in it, they start to look at us as a reference, so I feel like it’s just become a bigger thing. Some cinematographers do it because they want to direct. That wasn’t my case, but now you have people who are growing up wanting to be cinematographers, period. Obviously that existed, because that was me, but now, I have to say, I feel like there’s way, way more — and there’s more programs. It’s astonishing, really, and when I look at young people’s work — people who are in film school now — they’re so much more sophisticated because they have more access than we did.

When you come to an international festival and see a lot of films, are you still surprised or even inspired by what’s being put in front of you?

I love it. Sometimes you get really inspired; sometimes you’re ambivalent because you don’t like something or don’t agree with it. But I’m more ambivalent, in that case. I don’t tend to hate on people because I know how hard the job is. I appreciate choices, even if they’re the wrong ones. But, for me, I hope I’m seeing something that’s unusual to me; I want to be blown away. When I am, maybe a small part of me is, “Oh, fuck, why didn’t I think of that?” I think that’s natural, but typically that’s what I’m looking for. As a juror, I want to be blown away. Maybe it’s the usual suspects — Chivo or Roger [Deakins] or Chris Doyle — but it’s even more beautiful when it’s somebody you’ve never heard of.

Are these things fresh on your mind if you go right from the festival to a new project? Is that part of an ongoing learning process?

Absolutely. I don’t think I’m there yet; I don’t consider myself there yet. I mean, I know how to do the job, but I feel like every film that I approach is starting from scratch. Of course you’re taking everything that you’ve experienced in your career and life and you’re putting it into it, but to assume that I can fall back into a habit is incorrect — so I just start from scratch. I start to deconstruct a screenplay for myself, and start, brick-by-brick, trying to build a visual language. But I don’t tend to use films as a reference. I more use photography, and painting, because it hasn’t changed much; classical painting hasn’t changed much, so those references are stuck in your mind.

But photography is always evolving, so that’s what’s interesting, I think, for me when I’m trying to create an atmosphere or experience. I look at photography, because I just don’t want to bite people’s work, so I tend not to use other people’s work as a reference. But clearly you’re influenced by everything you see, so if I remember an image that I’ve seen in a film, say, here, I might subconsciously lighting a scene and not know it, but it’s not a thing I tend to try to do. Directors like to watch films a lot. I do watch them, but I’m talking strictly about creating an atmosphere. When you’re working with a director, watching a film is great because you’re having some base of common knowledge about how shot structure is, and getting a sense of how the director’s going to work editorially. So, in that regard, films are very important.

I’m excited that we’ll see more of you in just a few weeks, what with Chi-raq coming out. We’re very excited for it.

And I’m very proud of it. I’m most proud of it because I feel like it’s a true Spike Lee film, and, I have to say: this is my fourth film with him and I’ve never seen him so excited. He’s always been kind of a hero to me, so I always have to step outside of myself to make sure that I remember I’m a collaborator with him, but I don’t forget the fact that he was an influence. I’m really proud of the film because I think he really did his thing [Laughs] in his own specific way, you know?