Once upon a time, there was a magical, mystical time known as the 1980’s. I’ve always been slightly amazed at very young people who claim to love the 80’s. These poor, misguided souls always seem to have been born around 1987, and thus don’t know what the hell they’re talking about. I was a child during the 80’s and remember Ronald Reagan giving doddering speeches, the rise of Oprah and the sudden cultural whirlwind of a literary phenomenon called Stephen King.

I’ll spare you the protracted I-Hate-The-Eighties rant, because you’ve heard it before (in an ironic way, probably), but seriously, f*ck the 80’s. The best movies of the 80’s (Blue Velvet, Raging Bull, Raiders of the Lost Ark) exist outside of the place and time in which they were made. The great bands of the 90’s – Nirvana, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains – pumped that 80’s-metal sound full of heartbreak and bile and made rock awesome again. Like the misunderstood and easily-exploited 60’s, the 80’s was a decade of confusion, rampant conservatism and utter hypocrisy.

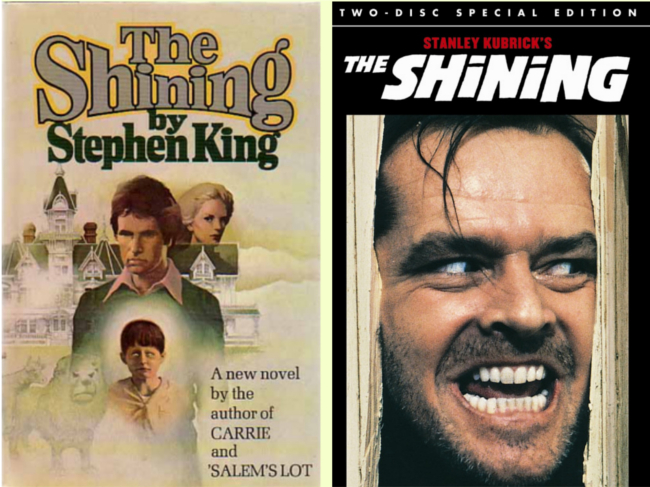

Like any other era, a handful of artists with particular talents changed everything forever. Keeping strictly to film, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas ushered in the Gilded Age of the Blockbuster, Ivan Reitman elevated the gross-out comedy to similar heights with Animal House and then both Ghostbusters movies, just to ice that money-cake. What Lucas/Spielberg did for the sci-fi/action set and Reitman did for comedy, Stephen King did for horror. He almost single-handedly dragged horror fiction into the modern era with his first two books, Carrie and ‘Salem’s Lot. The first was a disturbing treatise on how high school in American can quite seriously destroy people (while leaving us with the lesson that you shouldn’t fuck with a pyro-kinetic chick.) ‘Salem’s Lot was at the time considered one of the best treatments of the traditional vampire novel since Bram Stoker’s Dracula. And then, in 1977, King published The Shining.

Like any other era, a handful of artists with particular talents changed everything forever. Keeping strictly to film, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas ushered in the Gilded Age of the Blockbuster, Ivan Reitman elevated the gross-out comedy to similar heights with Animal House and then both Ghostbusters movies, just to ice that money-cake. What Lucas/Spielberg did for the sci-fi/action set and Reitman did for comedy, Stephen King did for horror. He almost single-handedly dragged horror fiction into the modern era with his first two books, Carrie and ‘Salem’s Lot. The first was a disturbing treatise on how high school in American can quite seriously destroy people (while leaving us with the lesson that you shouldn’t fuck with a pyro-kinetic chick.) ‘Salem’s Lot was at the time considered one of the best treatments of the traditional vampire novel since Bram Stoker’s Dracula. And then, in 1977, King published The Shining.

The fact that Stephen King is now a household name is as much due to the early film adaptations of his books as the books themselves. Brian DePalma‘s 1976 film of Carrie grossed thirty times it’s budget. That hit naturally spurred the already-impressive sale of his books and now, over 30 years later, the once critically-reviled author (who once bemusedly referred to himself as “American’s Shlockmeister”) is a respected cultural touchstone. In 1980, King was a young author with a handful of bestselling mainstream horror novels behind him. One morning, King was shaving (and nursing a hangover) when his wife told him that Stanley Kubrick was on the phone, and wanted to adapt The Shining. As the story goes, Kubrick immediately explained how ghost stories are optimistic, as they suggest humans actually survive death in a sense. Or something. There’s no way to tell what Kubrick was on about, really… despite how seemingly close King was to the development process (Kubrick would reportedly call the author at 3:00 AM and ask questions like “Do you believe in God?”), this adaptation of The Shining is definitely Kubrick’s vision of King’s book.

Which is something King never appreciated, evidenced by the slightly campy made-for-TV adaptation he wrote and executive produced seventeen years later. Directed by King’s favorite hack, Mick Garris (who also directed the multi-part adaptation of The Stand as well as the well-intentioned but deeply flawed Stephen King-Clive Barker project Quicksilver Highway), it is slavishly faithful to his novel. King voiced his dissatisfaction to American Film magazine in 1986:

“It’s like a great big beautiful Cadillac with no motor inside, you can sit in it and you can enjoy the smell of the leather upholstery – the only thing you can’t do is drive it anywhere. So I would do everything different. The real problem is that Kubrick set out to make a horror picture with no apparent understanding of the genre. Everything about it screams that from beginning to end, from plot decisions to the final scene.”

How could anyone not like this movie? It’s a cold, withholding, cerebral horror film – those three adjectives can succinctly describe almost any film by Stanley Kubrick – and though it deviates radically from the source material in certain places, there are other scenes which were taken nearly word for word from King’s book. The spine remains unchanged: recovering alcoholic (and frustrated writer) Jack Torrance moves his wife Wendy and young son Danny to the isolated Overlook Hotel in the mountains of Colorado in order to heal their wounds and escape his demons. The hotel has it’s own demons and they go to the work on the family, eventually driving the father to homicidal madness.

In the book, the hotel’s focus is the boy, Danny. The novel’s five-act structure (which corresponds to the turn-of-the-century play Jack is working on) carefully chronicles Jack’s mental breakdown. The hotel remains accessible for several weeks after the summer and spring crew leaves. King slowly turns the vise on the little family – a bug-bombed wasp’s nest suddenly comes alive in the middle of the night, and the little bastards attack Danny. Jack becomes more and more obsessed with the hotel’s dark past, to the point of calling his boss, edging to the point of blackmail in promising to pen a tell-all nonfiction book about the nasty things that went down in the Overlook and were swept under the rug.

In the book, the hotel’s focus is the boy, Danny. The novel’s five-act structure (which corresponds to the turn-of-the-century play Jack is working on) carefully chronicles Jack’s mental breakdown. The hotel remains accessible for several weeks after the summer and spring crew leaves. King slowly turns the vise on the little family – a bug-bombed wasp’s nest suddenly comes alive in the middle of the night, and the little bastards attack Danny. Jack becomes more and more obsessed with the hotel’s dark past, to the point of calling his boss, edging to the point of blackmail in promising to pen a tell-all nonfiction book about the nasty things that went down in the Overlook and were swept under the rug.

Kubrick ignores most of this. He introduces the hotel, Jack and his family, their situation (Jack will be the Overlook’s winter caretaker, cut off from the rest of the world for months – and there’s no booze around), and almost immediately leaves them alone in the cavernous Overlook. Kubrick loves his gigantic interior set, enhanced by the then-brand-new Steadicam, which floats dispassionately around the hotel – most amusingly, as it follows Danny through the halls on his Big Wheel.

The King-scripted remake was shot at the Stanley Hotel, which inspired the novel. Watching the TV-movie remake and then re-reading the book is interesting. King’s vision of the Overlook’s corridors was not the yawning, palatial set of Kubrick’s world but a cramped, labyrinthine web of hallways (which were always so harshly lit from below), possibly meant to mirror Jack’s madness as the hotel burrowed itself deeper into his mind. It’s a good metaphor, but the hotel’s interior was never plainly laid out in the book… and Kubrick clearly required a lot of room. His version of the Overlook is a massive, imposing space, with cinematographer John Alcott‘s natural lighting rendering it almost museum-like in it’s emptiness. Kubrick lets this vast, spooky set dominate our imaginations.

King’s book has the Overlook focusing on Danny and his powers – the boy seems to be a powerful telepath with limited clairvoyant abilities. Fueled the hotel’s depraved past, the demented ghosts seize control of Jack’s mind, driving him to stalk his own family through the Overlook, promising to bash their heads in with a roque mallet (an oversize croquet hitting-thingy). Oh, and there’s a batch of freaky hedge animals carousing on the hotel’s expansive front lawn which come alive when no one’s looking and eat you!

Kubrick diplomatically claimed that the technology didn’t exist to make the hedge animals work, but since this was the man who revolutionized visual effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the filmmaker most likely wrote the hedge animals off as lame and unnecessary. Instead, an immense hedge maze was constructed (it was so big that even crew members would reportedly get themselves lost at times). Is it meant as a metaphor, reflecting Jack Torrance’s disintegrating mental state? The shot of a clearly half-mad Jack staring into the hedge maze’s model as his family is outside wandering through seems to reinforce this idea.

For all of King’s disapproval, he seems to have missed (or willfully ignored) just how much Kubrick  appeared to have liked King’s language. The pivotal scene of Jack Torrance’s first real break with reality is the famous ballroom sequence. Pissed off at his wife, Jack wanders in and sits at the deserted bar, wishing for a drink. He looks up and begins a batshit-crazy monologue to an imaginary barkeep named Lloyd… and then, suddenly, Lloyd is there. Every word of this scene is nearly verbatim from the book, including Jack’s later exchange with Grady, after Jack looks around to discover a flapper-era masquerade party in full swing. In King’s remake, this was all completely re-written – it’s the one major deviation King made from his own book, and it’s clear he did so to distance his TV movie from Kubrick’s adaptation. And that’s a shame.

appeared to have liked King’s language. The pivotal scene of Jack Torrance’s first real break with reality is the famous ballroom sequence. Pissed off at his wife, Jack wanders in and sits at the deserted bar, wishing for a drink. He looks up and begins a batshit-crazy monologue to an imaginary barkeep named Lloyd… and then, suddenly, Lloyd is there. Every word of this scene is nearly verbatim from the book, including Jack’s later exchange with Grady, after Jack looks around to discover a flapper-era masquerade party in full swing. In King’s remake, this was all completely re-written – it’s the one major deviation King made from his own book, and it’s clear he did so to distance his TV movie from Kubrick’s adaptation. And that’s a shame.

Maybe King was offended by Kubrick’s ultimate break with the novel, when Halloran, the old cook played by Scatman Crothers, is summoned by a terrified Danny via his “shine,” Jack kills him with an axe. For anyone who’s read the novel, it’s a shocking moment; Kubrick’s “this is mine, bitch!” moment. At that point, we’re in no man’s land. Danny leads his insane father through the hedge maze, backtracks, finds his mom and together they manage to escape. Our last image is of Jack Torrance, frozen in the snow, clutching the axe, having lost his life along with his family and mind. In the book, the hotel explodes after Jack, gripped by psychotic lunacy (which makes it tough to do one’s job, as any cubicle worker will tell you) forgets to dump the Overlook’s elderly boiler. Was Kubrick’s ending a rushed cop-out? Not necessarily, for as Roger Ebert points out in his terrific Great Movies essay on The Shining, (via critic Tim Dirk):

A two-minute explanatory epilogue was cut shortly after the film’s premiere. It was a hospital scene with Wendy talking to the hotel manager; she is told that searchers were unable to locate her husband’s body.”

So what the hell? Ebert considers this film to be an exploration of a narrative whose characters’ perspectives can’t be trusted. The film’s famous final shot is the framed photograph from 1921, with Jack in the middle of a New Year’s Eve party, smiling and at home, forever the Overlook’s caretaker. Can we trust anything we saw? Re-watching Kubrick’s The Shining with these thoughts in mind is like watching Fight Club once you know the ending: it’s a mind-warping puzzle of a film, cold and terrifying.

There have been dozens of film adaptations of Stephen King books. Many of them are flat-out awful. The Shining is an example of how do it right.

Have you read The Shining? Seen the movie? Which did you prefer?