With the recent smashing success of Bridesmaids, much has been made about women in film. Supposedly, this one comedy proved once and for all that 1) People with uteruses can be funny 2) Female-fronted films need not be pandering 3) Men will actually pay to see movies with female leads, and 4) Carrots can be sexy. Now as much as I love Bridemaids and have steadily reveled in its worldwide success, I’m more realistic about its impact on the standing of women in Hollywood and as moviegoers. It’s just too soon to declare women have won the war against pandering, sexist and misogynistic movies that are theoretically aimed to entertain us. (Even though the surprisingly big opening of The Help is cause for optimism.) Now, I won’t bore you with the crushing statistics of the success rates of female filmmakers versus male filmmakers, or point out the dishearteningly wide discrepancy between the number of films with male leads versus female leads. Instead, I’d like to talk about the film genre most often targeted at women: romance. Because Bechdel test be damned, the romance genre is essentially synonymous with the dismissive “chick flick” moniker. Yes, if the trailer features string instrument swells over a kiss — be it rom-com or drama — it’s intended audience is us lady folk.

Previously, I have targeted the rom-com’s of Katherine Heigl for the sexist stereotypes they promote, but now I have a bone to pick with the tearjerker subgenre. In the past several years there’s been a surge in this brand of tragic love tales, largely thanks to the popularity of Nicholas Sparks’ novels and subsequent adaptations in which somber sweethearts valiantly confront major obstacles, from parental disapproval to impending death to military service to the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease, all in the name of love! Basically, it’s a particularly bleak subgenre intended to draw crowds of women toting Kleenex Travel Packs and looking for a good cry. At their best these movies can be cathartic fun, but at their worst they evoke the most egregious gender stereotypes and sexist ideology to spoonfeed devaluing life lessons to their often young and mostly female audience. And it’s the latest addition to these moody tales that has drawn my feminism-fueled ire.

Adapted from David Nicholls‘ heralded novel, director Lone Scherfig’s drama One Day aims to lure women in with a crush-worthy leading man Jim Sturgess, the cute but non-threatening romantic hero of Across the Universe, and a modern chick flick mega-star Anne Hathaway. Couple the casting with the sentimental trailer, passion-filled promotional poster and a PG-13 rating, and it’s clear that Scherfig and the film’s producers are gunning for a female audience that includes a large contingent of young and impressionable girls. This makes the film’s message of a woman’s worth all the more infuriating. To be succinct, through this story of frequently near-miss lovers, Scherfig seems to declare a woman’s purpose in life is to better the man she loves after sufficiently making herself worthy of his notice. It’s a demoralizing message that curiously devalues both men and women. And so I don’t come here to review One Day; I come here to eviscerate it.

Adapted from David Nicholls‘ heralded novel, director Lone Scherfig’s drama One Day aims to lure women in with a crush-worthy leading man Jim Sturgess, the cute but non-threatening romantic hero of Across the Universe, and a modern chick flick mega-star Anne Hathaway. Couple the casting with the sentimental trailer, passion-filled promotional poster and a PG-13 rating, and it’s clear that Scherfig and the film’s producers are gunning for a female audience that includes a large contingent of young and impressionable girls. This makes the film’s message of a woman’s worth all the more infuriating. To be succinct, through this story of frequently near-miss lovers, Scherfig seems to declare a woman’s purpose in life is to better the man she loves after sufficiently making herself worthy of his notice. It’s a demoralizing message that curiously devalues both men and women. And so I don’t come here to review One Day; I come here to eviscerate it.

Note: below I detail plot points, specific visual signifiers (particularly costuming choices) and dialogue in order to discuss the film’s overall themes. As such, there are heavy spoilers ahead. Furthermore, as a firm believer that a film adaptation of any kind should be able to stand up on its own, I will solely be discussing the film One Day, without further reference to the novel. Here “but that’s how it is in the book” will not serve as a valid excuse.

One Day centers on Dex and Emma, and essentially begins with their graduation from college, which Dex — with his tossled hair and laissez-faire sense of sexiness — believes is their first meeting. But bookish and bespectacled aspiring author Emma dutifully informs him that they have met before. Twice in fact. He looks her up and down. This is not the stylish and enviable red-carpet Anne Hathaway; this is beginning of The Princess Diaries Anne, complete with frizzy hair and gigantic glasses. Which is to say, of course he forgot her. Nevertheless, as an unencumbered horndog, Dex decides to cash in on Emma’s obvious crush and promptly propositions her. The two end up back at her apartment where Emma accidentally kills the mood with one of the saddest seduction attempts caught on film, complete with a mournful musical soundtrack and her donning cap and gown over embarrassingly white and matronly underwear. It’s pathetic, and Dex quickly pulls up his pants and utters those three hope-killing words, “Let’s be friends.” However, he does spend the night cuddling with her – and thus a long tradition of mixed signals and manipulation is born.

One Day centers on Dex and Emma, and essentially begins with their graduation from college, which Dex — with his tossled hair and laissez-faire sense of sexiness — believes is their first meeting. But bookish and bespectacled aspiring author Emma dutifully informs him that they have met before. Twice in fact. He looks her up and down. This is not the stylish and enviable red-carpet Anne Hathaway; this is beginning of The Princess Diaries Anne, complete with frizzy hair and gigantic glasses. Which is to say, of course he forgot her. Nevertheless, as an unencumbered horndog, Dex decides to cash in on Emma’s obvious crush and promptly propositions her. The two end up back at her apartment where Emma accidentally kills the mood with one of the saddest seduction attempts caught on film, complete with a mournful musical soundtrack and her donning cap and gown over embarrassingly white and matronly underwear. It’s pathetic, and Dex quickly pulls up his pants and utters those three hope-killing words, “Let’s be friends.” However, he does spend the night cuddling with her – and thus a long tradition of mixed signals and manipulation is born.

For much of the next 20 plot-jumping years, Dex is a self-concerned womanizer whose only discernible asset is his good looks, while Emma — no matter where life takes her — is his ever-doting cheerleader. It’s an almost entirely one-sided relationship. In fact, the closest thing to friendship Dex offers is some half-hearted but bad advice. When he is a trashy TV talk show host and she is a wallowing waitress at a London tex-mex restaurant, Emma laments her lack of professional momentum. So, Dex suggests she get a boyfriend. (Because that will give her life meaning?) But this is by no means a come on, as he soon clarifies, “someone like you…with the same glasses.” Cue the criminally unfunny stand-up comic/waiter with curly hair and huge specs of his own. Accepting what Dex deems her equal, she begins a long and lifeless relationship with her male doppelganger who lacks any kind of charm or ambition, while Dex dates a string of interchangeably glamorous and duplicitous blonds.

But eventually late bloomer Emma begins to mature, earning a graduate degree and becoming a teacher. Yet when she and Dex catch up over drinks, he, who is now a sleazy-looking cokehead and borderline has-been, mocks her for pursuing teaching instead of penning her oft-talked about first novel, snidely commenting, “Those who can’t do, teach.” Thankfully, Emma (with a straightened and sweet hairdo and a quirky but cute vintage dress) unleashes on him for his lack of support and general callousness. She has grown into a woman with a funky yet fun sense of style and a spine all her own! Shortly after literally and metaphorically walking away from a baffled Dex (how could she possibly resist his coked-up charms?), she dumps her comic beau and upgrades to ever-classier fashions. Emma is emerging to be the kind of ego-ideal and heroine a girl can and should aspire to!

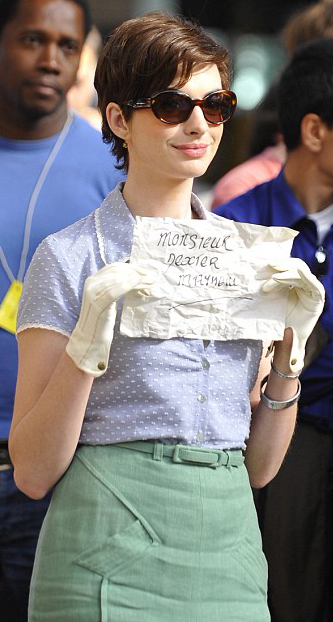

Years later, she and Dex make amends, and finally become a real couple. But the circumstances are disconcerting. While at this point Dex has learned to care for another human being — namely his darling daughter, the cuddly little catalyst to his shotgun wedding — he is in all other ways a complete loser. At the point he and Emma finally begin a romance, he is a broken-down, rudderless and cuckolded divorcee with clumsy salt and pepper hair, ill-fitting clothes and a scruffy day-old beard. On the other hand, Emma is now living in Paris as a successful novelist, and has grown from chubby duckling to svelt swan, sporting a glamorous tailored pencil skirt, heels and fashionable blouse, with a darling pixie cut and a charmingly self-deprecating sense of humor. She is now the girl typically seen as the heroine in romances. Sleek and lovely, she is now worthy of love. But since her Romeo currently resembles a battered stray more than the golden god of Emma’s idolatry, this development is troubling — especially when Emma casts aside a ruggedly attractive French jazz musician in favor of a sulking Dex.

The visual disparity in their appearance alone is striking. (It’s like Beauty and the Sex Offender.) But what it suggests about these characters status is even more shocking. To recap: when Emma was a frumpy loser with no career prospects, her romantic equal (according to Dex, the film’s ultimate protagonist) was a similarly stunted server with a hopeless goal. But now that Dex is the one who is lost, lonely and physically beat — he sees his romantic equal as wildly successful and enviably gorgeous Emma. This double standard asserts to impressionable audience members that girls should aspire to Lancome good looks to land even a once-handsome man. Then to add injury to insult, Emma’s life is abruptly cut short by a City of Angels-style plot twist. Now the movie is just about Dex and how he’ll cope with her death, which he does (in a word) abysmally. But after some gritty hysterics, Emma’s unfunny ex re-emerges with a pump yet plain wife (his apparent equal) to deliver to Dex his life lesson: “She made you decent and in return you made her so happy.”

Wait…Seriously?

Wait…Seriously?

So a beautiful young woman who wrote (presumably) inspirational books for girls is killed in a freak accident and the relevance of her life is reduced to her turning a vain, self-obsessed young man into a “decent” human being? This undermines Emma’s impressive transformation from doormat to self-empowered woman (most of which took place in Dex’s absence) by declaring it was only useful as a tool to snag Dex and inspire him to change. This suggests that a woman’s life goal should be to improve the man she loves, and if she has to become a model and bestselling author to garner that handsome waste of space’s attention, so be it! Ultimately, under its façade of sentimental romance, One Day utilizes the worst of rom-com conventions (the gorgeous career girl meets the sloppy manchild, a woman is not complete without love/marriage) and wraps them in a dulcet soundtrack that will make love-drunk teen girls swoon while taking these dehumanizing expectations to heart.

And while this message is damaging to girls, the one aimed at boys is equally demoralizing. Because if women are intended to make men better, the implication is that men are not capable of the kind of self-improvement Emma herself achieves. It’s a bleak worldview of co-dependence where men need women to improve them, and women need to improve themselves to deserve men’s notice and achieve their purpose. And so One Day becomes a tragedy of a different sort. Its message is backward and misogynistic, which is especially disappointing from a female director who so beautifully crafted the enchanting and poignant coming-of-age tale An Education. Based on the memoir of the early life of British journalist Lynne Barber, Scherfig’s film centered on a young Barber’s journey of self-discovery following an ill-fated May-December romance. It was understated and elegant and offered a flawed but inspirational heroine. Of course, there are shades of Lynne in Emma, but then the film’s final twist blatantly undercuts Emma’s existence and import.

Sadly, I expect One Day will do fine in theaters. And while teen girls idolize Dex and put pictures of Sturgess in their lockers, crushing on his dreamy hair and British accent, critics will likely give it a pass as they tend to for weepies starring non-pop stars. Because so little is expected of “chick flicks” and tearjerkers, I doubt anyone will acknowledge the dangerous message One Day lobs at its young and susceptible target audience. To proclaim that all our efforts of self-improvement are only valuable in so far as they may get us a guy is a thoroughly demoralizing message. Teen girls are already forced to face a barrage of marketing and magazines designed to make them feel unworthy. Should they really have to pay steep ticket prices to be so belittled?

What do you make of One Day?