2013 has been something of a banner year for the legacy of John Cassavetes, who would’ve turned 84 last week. In addition to the Blu-ray-upgrade Criterion performed on its epic box set (which includes five of the director’s best films, alongside a 200-minute documentary by Charles Kiselyak), Brooklyn’s BAMcinématek offered a comprehensive retrospective in July — one that included both the films Cassavetes directed himself and some of the paycheck-providing acting gigs he did for other filmmakers. (To be sure, the “paycheck” designation is not meant derisively: he may have used these performances to finance his own passion projects, but there’s nothing second-rate about genre efforts like Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby or Brian De Palma’s The Fury; even lesser-known works [à la Machine Gun McCain] have good qualities.)

BAMcinématek’s Cassavetes series in the summer was so popular, in fact, that they brought back five films — The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Love Streams, Minnie and Moskowitz, Opening Night, and A Woman Under the Influence — for encore 35mm screenings this October. And, judging by the affection shown for Cassavetes on the Internet in the days since his birthday, it would seem that this positive recognition is something that stands only to continue in coming years. That the reputation of Cassavetes’s films, meanwhile, is so firmly aligned with his grassroots working methods — small budgets, a recurring stable of actors, no studio oversight, elusive direction of performances — makes the process of studying his work all the more pleasurable and interesting.

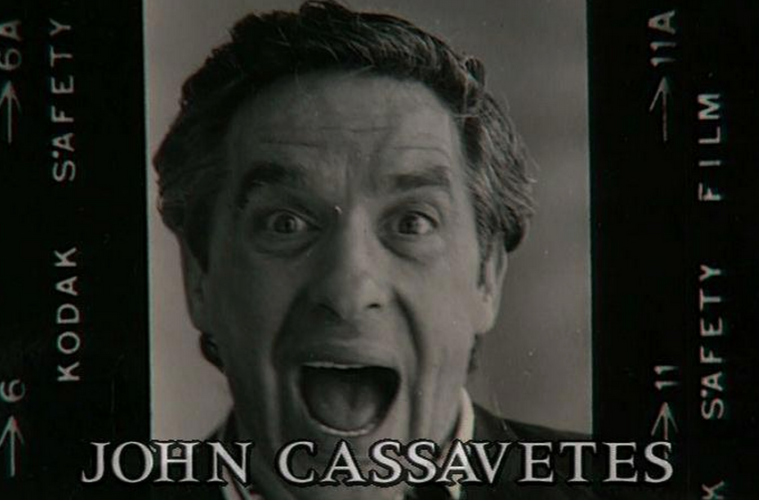

John Cassavetes: To Risk Everything to Express It All, a 50-minute 1996 documentary from Belgium-born filmmaker Rudolf Mestdagh, denotes a decent-enough starting point, and is available to watch in full on YouTube. It’s tempting, when praising Cassavetes’s films, to resort to generalizations about the director’s admirable intentions; descriptions like “original,” “raw,” and “human,” while certainly true, need to be expanded upon in order to get at what makes Cassavetes’s work special, and the film’s interview subjects sometimes fall into the trap of leaving things at the level of simplification. But for those new to the director’s films, there’s still some good material here: the commentary from Cassavetes mainstays Ben Gazzara, Gena Rowlands, Al Ruban, Seymour Cassel, and (especially) Peter Falk is predictably engaging, and the selected footage from formative early works like Shadows and Faces is revealing of a filmmaker in the process of discovering his voice.

You can watch the documentary in full below:

What did you think of the documentary?