Although his films are rarely filled with the obvious cinematic references that color the works of Tarantino, Matias Piñeiro’s films are a different type of cinephile’s delight, engaging essential questions of how we watch and think about movies. His approach — relaxed, inconspicuous, playful, and, at times, perhaps mystical — makes their engagement of these issues feel revelatory. Then again, Hitchcock didn’t make Rear Window as a film directly about screen-based scopophilia, and Piñeiro’s films are up the same alley. His first four followed young lovers in and around Beunos Aires, shape-shifting their way through the texts of Shakespeare, their country’s own history, and, most importantly, their own romantic relationships. The Princess of France, his fifth endeavor, is decidedly his most complex, an investigation into the idea of the off-screen — though that’s only scratching the surface.

The title comes from Shakespeare once again, the key text here being Love’s Labor’s Lost (as Viola was to Twelfth Night). Some of that plot transfers over here: in an early scene, one man explains its story to an audience member of a theatrical performance (who is also part of the show 00 there are no boundaries), noting that, despite the sacred oath, everyone will cajole on the promises to their lovers. But like Viola and the featurette Rosalinda, Piñeiro uses the text more as a sort of call-and-response to interests of the cinematic, the key here being how quickly people can change once out of our sight. The film’s opening scene might be the most wondrous and oddest contraption of this idea: a single shot overlooking an urban soccer match, in which characters seem to morph as they’re hidden by a spot in the frame. It’s a dazzling metaphor with a humorous final punchline, but also a key to reading the film: if people never remain the same, why should they be the same person when re-entering the frame?

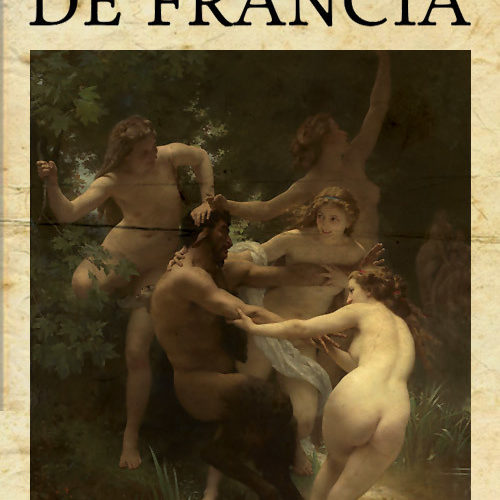

Piñeiro’s film thus proceeds with a cast of characters (whose names can become a bit confusing and hard to follow; a playbill with faces couldn’t hurt), but mainly follows Victor, an old friend who has returned from Mexico to put on a radio version of Love Labor’s Lost with his fellow friends and troupe members. But, more than anything, it is a chance for every character to shift their romantic interests and buried desires. The camera always feels like another character in the space. Piñeiro prefers long takes, but he moves more through close-ups and medium shots, so there’s always something going on just outside the frame that we can’t see. In a visit to a museum, Ana (Maria Villar), Victor, and another character wander around the art (notably the work of William-Adolphe Bouguereau) as Piñeiro uses the boundaries of space to slide these two into a passionate romance. The hidden desires of Victor and his women are always complicated through cinematic proceeding — voices heard but not seen, secret meetings that occur just off-screen, and passed notes that slip out of books.

What makes Piñeiro such a revelatory filmmaker (especially given his youth — he’s just over 30) is that these essential questions rarely burden the narrative focus of his efforts, which first engage our emotions in a playful manner. While The Princess of France is a comedy, it, like the Shakespeare play foregrounded within, is ultimately a dark and bittersweet tragedy. This is, after all, a story of lovers betraying each other. For every moment that delights in pure bliss, such as a wondrous montage of kisses to mark the passage of time, Piñeiro also cuts deep into that bliss. “This is a less than perfect moment,” one character writes to another as she abandons him, leaving us to contemplate what the perfect desire could be, an idea that returns in the film’s final, touching moment.

Cinema is a playground where ideas can be mixed and matched, an artificial territory for real emotions. The Princess of France shifts, in its latter half, to an extended sequence where one character attempts to get in contact with Victor. We see the same sequence in three different set ups; the locations remain the same, but the characters (and, thus, interactions) reveal different aspects of their personalities, though the goal of a sequence — a job acquired and a letter exchanged — remain the same. It’s this kind of play with the text which shows what isn’t revealed by narrative alone, as the sequence is followed by a series of Shakespeare line readings wherein each bit of dialogue is repeated with different music and inflections of voice, signaling how our readings of things change so easily, our focus not necessarily on what we are supposed to see. (Piñeiro, at one point, literally foregrounds “the wind of the tress.”)

Like Hong Sang-Soo’s progressing career of his small-but-similar films building on each other, Piñeiro’s oeuvre seem to be building into one great encompassing masterpiece (he has two more in the works). It can be hard to determine what the overall goal of his career may ultimately evolve toward, and The Princess of France is another film that, while satisfying in so many of its sequences, still remains beyond explanation, an experimenter in ideas and processes. But what a glorious experimenter. Why should films come fully formed with easily parsed themes and ideas? I’m more than glad to join Piñeiro on his road to discovering the potential of cinema, wherever it may go.

The Princess of France is currently screening at TIFF and will be distributed by Cinema Guild. See our complete coverage below and the trailer above.