It takes great maturity and confidence to make a film about the emergence of a young woman’s sexuality that also dares to ask complex, provocative questions while understanding there are no simple answers. Suzanne Lindon is such a filmmaker, and her brisk, entertaining debut Spring Blossom is such a film. Lindon directed, wrote, and stars in this remarkably assured story of a 16-year-old Parisian who falls for an older man. Though Blossom is a bit slight at just 73 minutes and sometimes prone to posing too many questions, this TIFF entry heralds the arrival of a major international talent.

Lindon is just 20 years old. (Her father is Vincent Lindon, the ruggedly handsome star of films such as Claire Denis’ Bastards.) Blossoms is not only her debut a writer-director, but also as an actor. As she explains in the film’s press notes, “I was 15 and it was the summer before starting high school and even though I was happy at school, with my friends or my family, I felt a certain melancholy. I decided to write about it; about this certain age, where you are not totally a child anymore, but not really an adult yet. I feel this feeling is universal and I was living it while writing the movie.” The resulting film has both the energy of a youthful creator and its flaws.

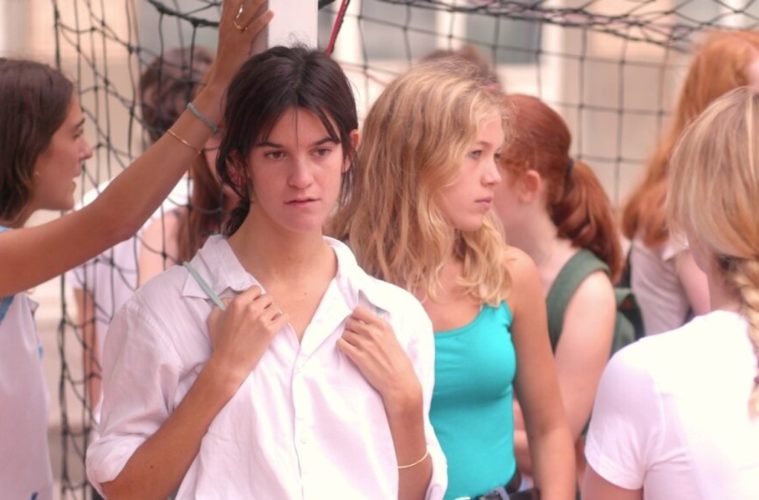

Our first glimpse of the teenage Suzanne and friends makes clear she’s not quite at ease in the company of others. Drinking her signature grenadine and lemonade while companions chatter away (“You are so naive” is a typical criticism), Suzanne seems to almost recede into the background. The same is true in her family’s busy home—when she explains that she has plans, her father remarks that “this is unusual; you never go out.” As Mary J. Blige’s “Family Affair” pumps at a party, she sits and drinks quietly. When a friend asks her to rate the looks of boys at the party, Suzanne responds with sweetness: “It’s horrible to rate people from 1 to 10,” she says. “I’d give everyone a 5.”

“You seem elsewhere” is a common refrain in Spring Blossom, and one element of youthful ennui Lindon gets right is this sense of never quite being present in the moment—always stuck between reality and daydream. No wonder, then, that Suzanne becomes quickly enchanted by the older man she spots every day on her path to and from school. He is Raphaël (Arnaud Valois, star of the great BPM (Beats per Minute)), an actor leading a local theater production. He is clearly many years older than she, a fact Raphaël clearly recognizes; one of his first questions to Suzanne is “How old are you?” Her response does not seem to phase him.

A rather slow courtship follows, in which Suzanne humorously starts bringing up many of Raphaël’s interests to her confused family—questions about scooters after seeing his break scooter down, comments on the theater after learning he’s an actor, a request for jam after spotting him eating bread with jam. Is this Lindon showing us how impressionable she is? Perhaps. She is young enough to still practice kissing in the mirror, after all. (The poster on her wall for Maurice Pialat’s À Nos Amours, centered on a teenager named Suzanne experiencing her own awakening, is a clever detail.)

This section of the film features a notable break from reality. It is a sequence of great humor, a lengthy shot wherein Raphaël asks Suzanne to listen to part of an opera on his headphones. He watches her intently as she listens until their movements suddenly match. Their heads, arms, and hands begin to move in unison. It is delightfully choreographed and quite funny. It’s also a surprising touch for a film which is rooted in reality, often featuring handheld camerawork and natural lighting.

For many viewers, the nature of the relationship between Suzanne and Raphaël will be considered unrealistic. It is presented with very little drama and nearly no consternation. At a post-show party with Raphaël’s theater friends, the couple’s hand-holding raises no eyebrows, while Suzanne’s late-film admission to her mother—“I fell in love with someone. I fell in love with an adult. And he’s in love with me too”—is unquestioned. These elements are why Spring Blossom’s focus on not providing answers or pat explanations is occasionally hard to take. Yet keen eyes will see that Lindon hints at these answers in facial expressions and movements. The ending is sudden and ambiguous—but we can interpret what’s next. It’s a moment when Suzanne seems to mentally mature and realizes it.

Lindon’s performance as Suzanne is wholly natural. The character’s thoughtful nature is easy to read as flat, but this is not the case. There is much happening internally, especially in a telling scene in which Suzanne slides to the ground, reading, while her classmates above complain about the cafeteria food. The other actors do not fare quite as well. The role of Raphaël feels dull and underwritten, and, outside Suzanne’s father, we get little sense of her family. These are the aforementioned flaws of a young writer-director, and none torpedo the film. Suzanne Lindon is an undeniable talent, and with Spring Blossom she’s crafted a genuinely involving slice-of-life tale. That’s no mean feat at any age.

Spring Blossom premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.