Heinrich Senft (Heinz Trixner) is alone on his little patch of land within a gated senior citizen community, his pension sustaining ready-made meals and the care for his dog Argus. When the latter passes away suddenly in the night, Heinrich has nowhere to project his grief but the veterinarian who sold him the vitamins he’s quick to blame for the pet’s demise. Unable to afford to have her pick the body up, he decides to bury it in the backyard despite being ninety years old with nobody capable around to help if something goes awry. Lucky for him, the only damage caused by a fall after hooking his pickaxe to an old tree stump’s roots is to his wallet. Eight Euros for a new handle is a rip-off.

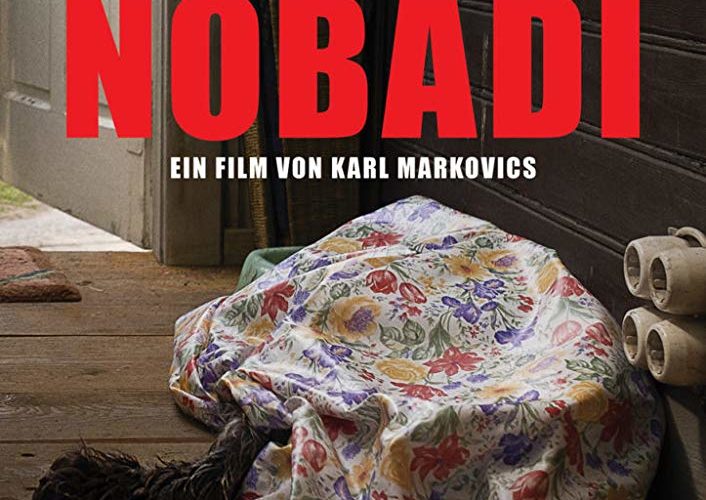

It’s an oddly funny start to Karl Markovics’ Nobadi—this frustrated and ornery old man shaking his fist at fate for making his day so much worse than he had planned. The tone carries over onto newcomer Adib Ghubar (Borhanulddin Hassan Zadeh) too, his Afghan migrant in Austria limping to the far side of a prospective employer’s truck to sneak in while the group of other undocumented workers fight about who should go. They ultimately drag him out and push him on his way, a forlorn look at the camera turning quizzical upon seeing Heinrich in the distance with a wooden handle in his hand. If Adib follows this stranger home, maybe he can earn a few bucks in exchange for hard labor. Anything is better than nothing.

The result is an odd couple pairing with political and racial undertones as Heinrich hides his money under plates and a gun with the silverware, preparing for the worst. Adib hasn’t done anything to warrant this treatment, however, so his youth and skin color become our only means of interpreting the white homeowner’s actions. Talk about working at “camps” ignites with obvious tension and perhaps guilt (Which side was Heinrich on?) before the first of many verbal scuffles spanning generational, religious, and cultural divides. Assumptions run rampant and a flirtation with dementia threatens things to take a turn for the worst until contrition and anger facilitates these two men going their separate ways. That’s when Markovics advances his story to arbitrarily tragic and violent ends I couldn’t embrace.

Not to give anything away, but the back half of Nobadi is sparked by a life or death revelation that leads to an out-of-nowhere instance of brutality we’re asked to accept as a necessary evil because the world is unfair. It arrives as a trade (a moment of cruelty for the hope of salvation), wherein we must treat one character as less than another in a way that’s too flippant to ignore. And to what end? Whether or not the person committing this atrocity gets away with it or succeeds upon the mission it makes possible, the film’s conclusion will always be bleak and devoid of any real insight or lesson learned. We’re therefore led to gory, sociopathic places that ultimately dehumanize the last bastion of humanity left.

The idea that white men can bury their demons and move on with their lives while POCs can’t arises as an afterthought to a desire for making amends that’s never earned. And it all stems from the script since Markovics’ direction is effective and the performances from Trixner and Zadeh imbued with complexity. The former’s penchant for confusion and the latter’s bad fortune doesn’t, however, clear a path for the plot’s ambitions to escort us to Hell without warning or purpose (at least none I see as an outsider to both their countries). The addition of a metaphor to Homer’s Odyssey only muddles things more besides what’s between the lines as far as the grey area of healing those you’re also persecuting. Heinrich’s motivations are thus forever clouded.

Putting these two characters in such close quarters does provide an environment for some heart-wrenching moments, though. It’s inferred that Heinrich has seen too much death already and wants to finally stop that pattern within his life (even if he fails miserably in that goal), so there is some warmth breaking through his prickly exterior when pushed to the brink of civility. And our knowing there’s more to Adib’s past than what he initially shares lets the truth he exposes hit with an emotional wallop even if what he says falls on deaf ears. But the fact we only get the opportunity to see and hear these things from the “convenience” of murder means any empathy I might have felt was negated by Markovics’ pursuit for hollow provocation.

Nobadi premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.