Despite the fact that Ziad Doueiri’s (a crew member on some of Quentin Tarantino’s early works) latest film The Insult is set in Lebanon, the ensuing drama can’t help but feel familiar to what’s currently happening in America. As our president says bad things are happening on “both sides” and that there are “good people” being “wrongly maligned,” we know the truth. Or at least we should. Whether or not his words are objectively correct, they fail to acknowledge that those “good people” are aligning themselves with hateful, racist notions while hiding behind politics or religion as though either is a valid excuse for a lack of simple humanity. We’ve found ourselves defaulting towards sanctimony, declaring our beliefs righteous without a care for truth or context. And nothing can ever be solved if we remain too prideful to admit we are wrong.

The big difference between a small subsection of America embracing xenophobic ideals (and aligning themselves with the Nazi cause as though doing so has no historical significance) waging war against refugees alongside anyone who might be Muslim and what’s happening in the Middle East (namely an influx of Palestinians to a Christian-majority section of Lebanon as far as the film is concerned) is that the former is a product of baseless fear. The latter isn’t … quite. The hate they feel is formed from civil war and constant turmoil with a body count and nightmarish memories. No “alt-right” white man forming his own militia can legitimately argue a child refugee is his enemy. He can’t feasibly lump them into a category of “terrorist” out of bloodlust either. The leading men in Doueiri’s film unfortunately can. They shouldn’t, but you can hardly blame them.

As such, the smallest of disputes can have devastating consequences. When a Palestinian (Kamel El Basha’s Yasser Salameh) does his job (albeit as an illegal worker) to fix a Lebanese member of the Catholic party’s not-to-code gutter (Adel Karam’s Toni Hanna), it should be an inauspicious event. But their ethnicity, religion, and the bigotry formed from both renders it the opposite. The latter dismisses the former before he can even explain what needs to be done. The former does it anyway only to have the latter destroy his work. What follows is an otherwise unsurprising result: Yasser calls Toni a name. Suddenly things escalate to DEFCON ONE. Toni wants an apology, Yasser doesn’t believe he owes one. The more things fester the more Toni seethes. Now it’s his turn to insult with hate speech and Yasser moves onto physical assault.

It’s an unfortunate conflict born from the pettiest of actions steeped in generic bile. Their wives get it (Rita Hayek’s pregnant Shirine and Christine Choueiri’s Manal), but their words mean nothing when male pride is on the line. Things exacerbate further and a trial commences as Toni sues Yasser for damages stemming from the injuries that begat injuries that begat injuries. High-powered attorney Wajdi Wehbe (Camille Salameh) takes Toni’s case with ulterior motives considering the fight has Catholic overtones and Yasser is approached by a young lawyer named Nadine (Diamand Bou Abboud) looking to make a name for herself on the side of moral high ground. But as things get heated and “man’s nature” debated, the quarrel spills out of the courtroom and into the streets. This squabble begins to stand for a nation’s unrest.

How Joelle Touma’s script progresses is heavy-handed in its desire to augment the tensions and provide justifications, but it’s still powerful nonetheless. You may initially believe one man over-reacted more than the other with both seeming guilty in equal measure, but prepare to wonder if both are actually innocent as more secrets and truths are revealed. Anyone who says wars cannot start as a result of words need look no further than this ordeal because passion will cloud better judgment when deep-seeded feelings fail to look past surface vehemence rooted in emotional baggage rather than intellectual discourse. As soon as things get personal, clarity goes out the window and a storm brews with the potential of abject destruction. The judge jokes about having to wear a bulletproof vest and you can’t quite laugh because it’s true. Who’s to say tragedy isn’t on the horizon?

For a good two thirds El Basha carries things with his Yasser’s conflicted psychology. A good man and hard worker, his aggression can get extreme while remaining authentically drawn. But the third act allows Karam some room to move his Toni past being the one-note instigator he can often seem. There’s more than meets the eye as far as why he feels the way he does about Palestinians and why he so devoutly follows the Catholic party and the incendiary views of a past leader. He finds an intriguing duality as far as dragging a petty disagreement before a judge despite not wanting monetary damages. Unfortunately any chance at receiving the apology he demands is to take things to this higher level and risk embarrassing his entire family in the process. Fault is a rabbit hole of intent.

This is where The Insult excels: showing how easy it is to find the hypocrisy in one’s actions if he is forced to face it. So often we find ourselves caught in a vacuum of sycophants that it’s easy to forget we are all flawed and historically responsible for heinous crimes rooted in prejudice. We are generally unaware of exactly what our enemy’s struggles are and how alike we ultimately prove when moving past rhetoric ingrained into us by religious and/or political zealots on their quest towards power. To ascend is to defeat; to be right is to need someone who isn’t. Rather than treat people as neighbors by default, we let suspicion and paranoia keep strangers at arm’s length. Push them away and they do the same. Hate them and they hate you. And it doesn’t matter who started the conflict, just who’s willing to step up and solve it.

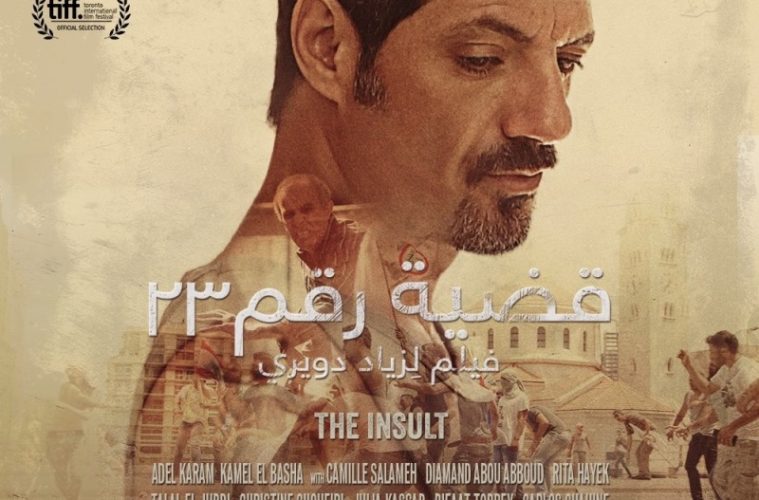

The Insult screened at the Toronto International Film Festival and opens on January 12.