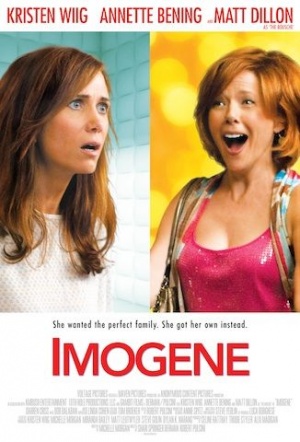

Imogene begins with a childhood flashback of a young girl, which is then followed by an extended point-of-view shot of the same woman many years later. While these are two distinctly different forms of cinematic storytelling, they each try to establish that this will be a film that explores womanhood and its challenges and inherent humor. The woman at the center of this is, of course, to be portrayed by Kristen Wiig.

What brought Ms. Wiig to fame was without a doubt her seven-season tenure on Saturday Night Live. She became the star of the show because of her range of characters, from the easily excitable Midwestern Target Lady to the devilish middle-school student Gilly. While each of these personas were distinct, they showed that Wiig was somewhat of an “auteur” actress. Her vocal and facial ticks; often inward speaking and subtle-to-the-point-of-exaggeration movements with her mouth were definitely “of a piece.” But her talents were transcended when she appeared in Bridesmaids, the 2011 surprise smash that showed her able to form her shtick into an actual human character. That’s why it’s a shame her newest starring vehicle (even though she’s part of a distinct ensemble), another attempt to blend comedy and pathos, falters so noticeably on both counts.

Imogene, from American Splendor (let’s forget they did The Nanny Diaries) directors Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini, as well as writer Michelle Morgan, centers on the both emotionally and creatively frustrated title character. Her boyfriend has broken up with her, and her playwright experience has to be put towards a career of giving five-sentence synopses for other plays.

This leads to her faking her own suicide, and upon being discovered, being put in the hospital and into the care of a loved one, her estranged mother Zelda (Annete Bening), who we learn is known for her gambling and negligent parenting. This takes her to her small hometown in New Jersey, where she encounters her brother (Christopher Fitzgerald, who resembles a dumpy Harmony Korine) as well as her mom’s new secret-service agent boyfriend (Matt Dillon) and an underachieving hunk (Darren Criss). From here we get her journey to find her thought-to-be-dead father as well as come to terms with both her family and her self.

The problem is that everything feels half-hearted, from the aforementioned pathos to the film’s odd stabs at formalism. Films like these are certainly a tricky balancing act, because they need to be able to communicate universal human truths through broad humor. Having a montage of Imogene preparing her “suicide” set to poppy music evidences this challenge. But the film’s various jokes are also often at the expense of the characters, and never transcend that.

Matt Dillon’s character serves as the prime example; certainly the actor sells the comedy through a certain conviction but even with that, do we ever believe that him and Zelda are a real couple? Essentially, all the quirk adds up to nothing; passable gags that fade away three seconds later. Imogene fails because the human pain at its center never co-exists with the comedy.