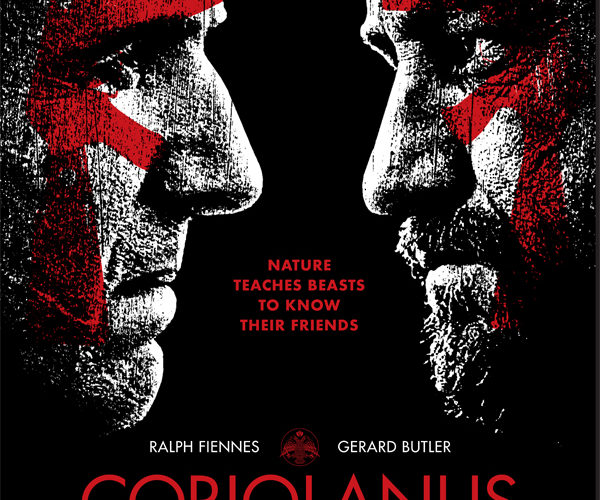

For his first directing effort, Ralph Fiennes took the bold move of adapting the work of one of our top literary icons, William Shakespeare. Brought to screenplay form by John Logan (Gladiator, The Last Samurai), the classic tragedy is updated to a modern setting. But don’t let the many explosions, blood, gunfire and gritty guerrilla style in the marketing fool you. Heavily trimmed, Logan has still kept the iambic pentameter Shakespeare vernacular intact for this story of politics and betrayal.

Fiennes is Caius Martius, the piercing general of a war-torn place “calling itself Rome.” Locked in a never-ending battle with the neighboring Volsces, headed by Martius’ utmost enemy Tullus Aufidius (Gerard Butler), we soon find the two powers in combat. Shot by The Hurt Locker‘s Barry Ackroyd, the verite style inspired by Gillo Pontecrovo’s The Battle for Algiers is quickly realized.

There is an initial disconnect with the modern setting and close-quarter cinematography, contrasted by the precise rhythm of Shakespeare’s words, but once it is clear our thespians are ferociously committed to these theatrics, all is right. While the supporting cast is strong across the board, Brian Cox, as friend and political aide Senator Menenius, and Vanessa Redgrave, as Martius’ loyal mother Volumnia, feel specifically built to deliver these words. Each exchange involving the two comes off elegant and genuine, not to mention the continuing powerful presence of Jessica Chastain as Virgilia, the mostly quiet wife of Martius.

There is an initial disconnect with the modern setting and close-quarter cinematography, contrasted by the precise rhythm of Shakespeare’s words, but once it is clear our thespians are ferociously committed to these theatrics, all is right. While the supporting cast is strong across the board, Brian Cox, as friend and political aide Senator Menenius, and Vanessa Redgrave, as Martius’ loyal mother Volumnia, feel specifically built to deliver these words. Each exchange involving the two comes off elegant and genuine, not to mention the continuing powerful presence of Jessica Chastain as Virgilia, the mostly quiet wife of Martius.

Prominent actors choosing to adapt plays for their directorial debut is usually a safe haven. Philip Seymour Hoffman did it with little flair last year through Jack Goes Boating, but Fiennes goes above and beyond, creating a brutal, extensive world within Coriolanus. Although he performed the play himself in 2000, the actor-turned-director rarely attempts to visually replicate the stage experience, as he and Ackroyd continually keep the camera moving.

This choice makes for a heightened sense of momentum, which matches the utter intensity Fiennes brings to the lead role. Not dissimilar to his In Bruges boss character, Fiennes has turned his notch up to eleven here. For particular scenes, such as one in which Fiennes is exiled from Rome, it works. For others, it’s made precisely clear why he is still operating on all cylinders, resulting in a numbing effect and bringing the rest of his peaks down. That said, one thing is for certain: Shakespeare’s writing is still as prevalent as ever.

This choice makes for a heightened sense of momentum, which matches the utter intensity Fiennes brings to the lead role. Not dissimilar to his In Bruges boss character, Fiennes has turned his notch up to eleven here. For particular scenes, such as one in which Fiennes is exiled from Rome, it works. For others, it’s made precisely clear why he is still operating on all cylinders, resulting in a numbing effect and bringing the rest of his peaks down. That said, one thing is for certain: Shakespeare’s writing is still as prevalent as ever.

By keeping his original lingo, it forces us to follow the exquisite poetry closely. With many dramas of the like repeating similar everyday language, it is refreshing to see Fiennes take a risk here. Some expository BBC news-esque broadcasts seem out of place and interest wanes during overlong stretches of dialogue, but Fiennes’ vision of Coriolanus remains a brute tale of authority and what happens when power oversteps its boundaries.