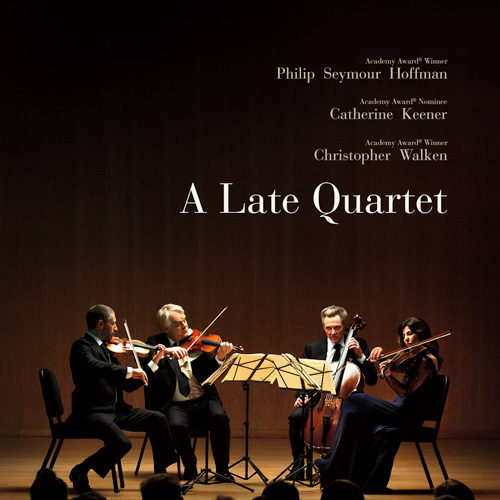

When the cellist of a world-renowned string quartet discovers early onset Parkinson’s is taking away the dexterity needed to continue playing, the will of the entire group is shaken. Conversations about a replacement, questions about continuing, and attempts to keep their friend’s desire to play alive unsurprisingly ensue while a comic series of sexual trysts add to the fun. This is Yaron Zilberman’s A Late Quartet — a tale of the conflicts inherent in any collaboration spanning twenty-five years mixed with silly asides doing more to sensationalize than service the plot. A light comedic drama with an A-list cast, the film’s saccharine undertones prevent it from being more than the throwaway rental it is.

Co-written by Seth Grossman, it is an interesting take on an orchestral world most probably assume is stuffy and devoid of salaciousness. Treating the Fugue Quartet as a rock band in some respects, what we actually see is the family-breaking stress a tour on the road can yield, the pressures of being both great and fresh despite playing the same piece for a quarter century, and the conflict of personal and business relationships locking horns. At times it’s almost as though we’re watching the string version of Fleetwood Mac with the close-knit group possessing surrogate fathers, ex-boyfriends, current husbands, and lustful romances as the first wrench thrown into their long tenure completely derails the idyllic troupe.

Egos are unleashed as second violinist Robert Gelbart (Philip Seymour Hoffman) decides it’s time to alternate solos in tandem with first chair and group creator Daniel Lerner (Mark Ivanir) as Robert’s wife Juliette (Catherine Keener) on viola refuses to accept Peter Mitchell’s (Christopher Walken) retirement. Some want to respect their friend, mentor, and former teacher’s wishes after already having lost his wife a year previous while others believe he’s giving up. And with the turmoil coming to a head as their season’s first concert approaches to a plethora of unresolved issues, all must reconcile feelings for the quartet against those of their friendship and decide what they truly desire. Maybe it’s time to stop; maybe it’s an opportunity for reinvention. Or perhaps it’s simply an excuse to finally follow their hearts.

Finding it projecting the technical and emotional aspects of playing onto the lives of three generations of musicians, A Late Quartet hits you over the head with the added of romantic crises. Rather than be content by looking into the struggles of a degenerative disease and its effect on the victim and those close to him, the foray into sexual escapade can feel tacked on and over-the-top while slighting the seriousness of Peter’s affliction. We begin to forget this could be a great man’s last performance or how he accepts it after realizing the Fugue was the second chance he never thought he’d have. Old chums with Juliette’s mother, the age difference always meant he’d be bowing out early whether he liked it or not. Watching this internal battle to be at peace is the film’s best aspect.

But the filmmakers needed to put the other actors onscreen and decided to let lust be the driving force. Hoffman’s Robert has his escalating flirtations with the gorgeous Liraz Charhi; Keener’s Juliette’s friendship with ex Daniel may or not may contain a longing for the past; and Daniel’s meticulous perfection at the violin ends up impressing the unlikeliest of fawners—or perhaps not in context with the contrivances—in the Gelbart’s daughter Alexandra (Imogen Poots). Love becomes skewed and desire replaces practicality when selfishness leads all away from the reason they came together in the first place. They’ve lost the music and its subtle beauty in the chaos of change. As a result of this overt melodrama, however, I found myself caring less and less about these morally gray people finding happiness.

And so it becomes Walken’s character’s job to ground us again by reminding what really matters. Despite being tough to look past his eccentric cadence and the unavoidable reality that he is Christopher Walken, somehow the role I couldn’t quite accept at first becomes the most authentic. We see the pain of his decision wrought on his aging face mixed with the need for the kind of relief only knowing the Fugue will live on without him can bring. But even his Peter ends up throwing me for a loop with a selfish demand of his own, ordering his old friend’s joy extinguished for the good of the group. When did these four become so close-minded and vengeful? The impending finish to their union is only the catalyst—these trapped feelings must always have existed.

With great acting—Ivanir’s dry, taskmaster’s thaw a highlight—and high production value, the film sadly collapses under the clichéd drama padding its run time. And it’s a shame too because the wait to finally experience Peter’s decision does payoff with a moving, heartfelt scene. The filmmakers bite off more than they can chew as the story spirals out of control, leaving the music behind. I guess this mainstream approach to making a niche subject accessible could be a good thing for a lot of viewers, though. I just wanted more about the musical world they inhabit, more with the “Behind the Music”-esque history on the Fugue and less their mid-life crises in the annals of love. I’ve seen the latter too many times before.

A Late Quartet is screening at TIFF and opens on November 2nd.