There was a time when Japanese filmmaker Kijū Yoshida was a cinephile’s mark of exquisite taste. While not entirely obscure, his work has been less-discussed than those of contemporaries Ōshima, Imamura, and Suzuki, even if he’s always been grouped among them as a key author of the Japanese New Wave.

In the early years of online cinephilia, mentioning Yoshida was a sort of a code, a way to signal that your knowledge about Japanese cinema from that era was a bit more nuanced. It is, in many ways, thanks to this interest that these films are more widely talked-about and now the subject of Film at Lincoln Center’s retrospective running from December 1-8.

My introduction to Yoshida’s cinema came courtesy Allan Fish, a self-taught critic who watched films (and TV) from all over the world and wrote vivaciously about the moving image on his blog Wonders in the Dark.

Fish usually put forward outrageous claims to differentiate his stance from mainstream critics. One is that Kijū Yoshida wasn’t only the greatest Japanese director, but had also made the best film ever: 1969’s Eros + Massacre. While that has become the de facto recommendation to those who want to know about Yoshida’s style and work, I feel it would be a fitting tribute, for both filmmaker and critic, to work our way through his career and find what led to that masterpiece.

His debut feature Good-for-Nothing (1960), while far from perfect, already demonstrates a complete grasp of the medium: busy and frenetic street scenes, use of stock footage as a way to creatively edit a lecture on anthropology, and a spectacular jazzy soundtrack. (This has often been compared with Godard’s Breathless and the French New Wave at large.) The title character is a young man who struggles with ennui, trying to find a way to love a secretary while being surrounded by bad elements that drive him to crime and death. Besides those creative jolts, Good-for-Nothing strains to concern the young generation’s malaise with the state of an extremely capitalistic post-war Japan, making it look as if it’s trying very hard to be “a generation’s film.”

Blood Is Dry (1960) continues (and surpasses) a thematic line started ten years earlier in Akira Kurosawa’s Scandal, another harsh critique of mass media and advertisement. It’s an interesting triptych featuring a man who fails to commit suicide when trying to defend his colleagues who were about to be mass-fired, the advertisement executives of an insurance company that wants this man to become the face of a new campaign, and the paparazzo who try exploiting the story.

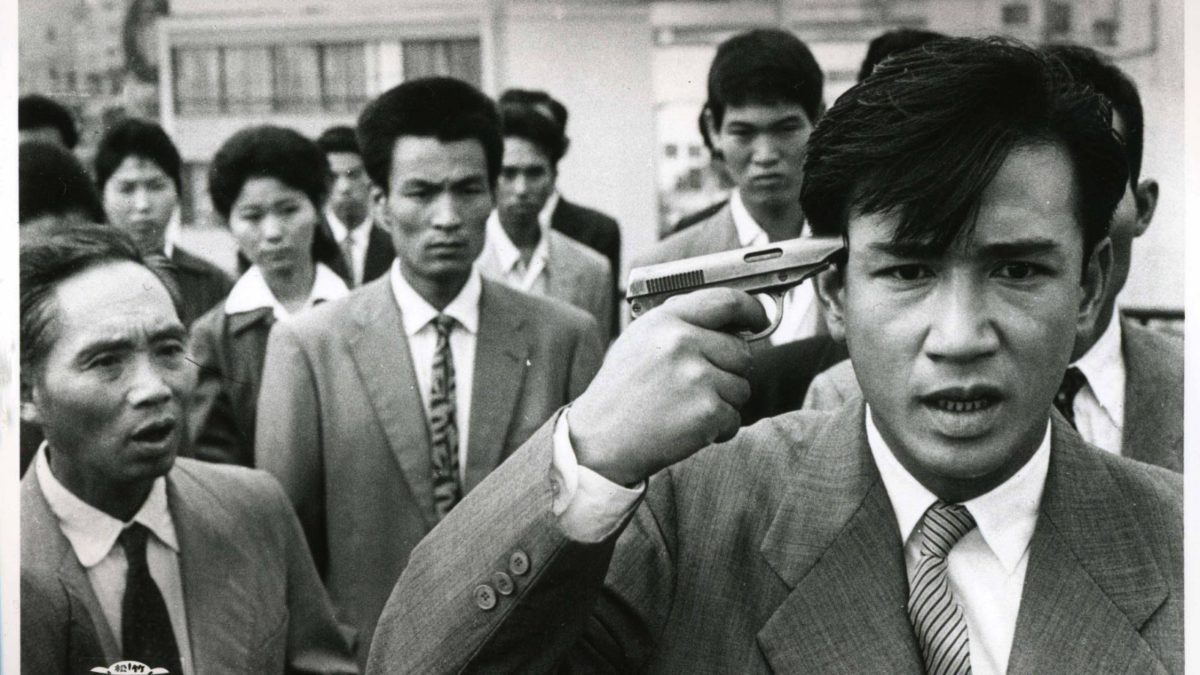

All of these strands interweave and move together to produce a portrait of modern society that is sometimes comical in its grim nature (giant billboards of a man holding a gun against his head to sell insurance) and at others extremely violent (kids in the street playing around, imitating the man that appears on TV with a gun to his head).

Blood is Dry. (c)1960 Shochiku Co., Ltd.

With Akitsu Springs (1962), Yoshida manages to veer from studio mandates and create something that feels personal and breathes on its own, making even greater that it became his first hit as a director. The film, in color, concerns a very sick young soldier fleeing the consequences of World War II and his falling in love with the innkeeper of hot springs in the small town of Akitsu. Its innovative structure captured the imagination of audiences.

Its first third is focused on Shusaku (Hiroyuki Nagato) and Shinko (Mariko Okada), how they meet, and how she (thinking he’ll eventually die) takes care of him. A pivotal moment that reverberates throughout is the surrender speech made by the Emperor on August 15. Shinko runs to the inn and enters the room where Shusaku convalesces, falling to her knees, crying and saying that Japan has lost. After they try (and fail) to commit a double suicide, Shusaku recovers, departs Akitsu without notice, and leaves Shinko longing for him.

The rest of Akitsu Springs is set across 17 years, divided into three times wherein Shusaku returns to Akitsu and meets with Shinko. Heartbreak is palpable when we find out for the first time that he’s married, then on a later visit when we realize the hot springs will close.

The conversations between them, the melancholic music, and the creative framing throughout (using doors, windows, shapes, shadows) makes it one of Yoshida’s most vibrant, emotionally harrowing works. It’s also his first collaboration with Mariko Okada, who’d become his wife and muse for the rest of his life.

18 Who Cause a Storm (1963) is perhaps stranger, more mainstream fare, but still an accomplished object. Shimazaki, a shipyard worker whose drinking puts him in constant money problems, is hired to lead a group of 18 young men who have been brought from all over Japan to work and sleep in a bunk house. The film feels “bigger” in scope––at times it plays as an ensemble piece with long shots of big groups of these “bunk boys” working, playing, fighting, and running together.

18 Who Cause a Storm sadly devolves into a romantic drama; Shimazaki’s relationship with a woman becomes endangered when she gets raped by what everyone assumes is one of the “bunk boys.” Yet there are moments of triumph as the film delves into subjects that contemporary Japanese cinema didn’t have interest in: working conditions, savage capitalism, the necessity of unions, and work strikes.

A Story Written in Water (1965) and The Affair (1967) form a curious pair connected by how the adulterous protagonists seem condemned by the action of their mothers. Both of these films mark an incredible advancement in cinematography and direction for Yoshida, who becomes a master of the geometrically framed shots that capture the most desperate moments of a human’s soul.

While clearly influenced by European directors from the time, there’s a certain kinship in these two films with the cinema of Luis Buñuel. The abundant use of dream sequences and metaphors create a complete psychological portrait of these protagonists, how disturbed they’ve become from their estranged or inappropriate relations with their mothers.

In A Story Written in Water, Shizuo (Yasunori Irikawa) has a dream in which a wake is held by all the women he’s met in the past few months––among them his bride-to-be (Ruriko Asaoka) and mother (Mariko Okada), both of whom he feels a strange attraction for how enticing everyone else finds them. The funeral court moves into the ocean and we realize, moments before he wakes, Shizuo is the dead man being carried away.

The Affair. (c)1968 Shochiku Co., Ltd.

In The Affair, Oriko (Okada once again) constantly faces visions of her mother crushed by a truck while returning from a lover. Sometimes the driver of the truck disappears or the matriarch is replaced by Oriko, a confirmation of what she believes is happening in her life: she’s becoming just like her mother.

Flame and Women (1967) might be the closest Yoshida came to full-on horror, but with enough particularities that render it particularly shocking for its time––including artificial insemination, a fertilization technique that would only become common in the 1970s. Tatsuko (Okada) has unwillingly gone through the process at the request of her infertile husband, but grows uneasy over the identity of the man who donated the sperm.

The film’s central sequence is essential to understanding Yoshida’s work with images and their inner rhythm: Tatsuko remembers a summer spent alone in the countryside, during which she was confronted by a nearby farm worker who broke into her abode and, finally, had sex with her.

The use of flashbacks, recollections, fantasies, and dream sequences––especially in such a silent, highly aestheticized way––recalls narrative elements that define the most-popular works of Latin American literature (e.g. Julio Cortázar, Alejo Carpentier, and Jorge Luis Borges) and had already influenced European art cinema.

Affair in the Snow (1968), the last black-and-white Yoshida film made before his groundbreaking Eros + Massacre, is among his best-regarded, and the first I ever saw under the influence of Allan Fish. What he had to say about it still resonates today: “Almost Nietzsche-like in its simplicity, it’s one of the greatest analyses of sexual need in world film, stunningly acted, not least by the superb Okada, and with photography that ranks among not only the greatest of Yoshida’s career, not only in Japanese film, but in world film.”

Lincoln Center’s retrospective would’ve greatly pleased Fish, whose goal in life was to spread what he thought was the world’s greatest cinema.

The Radical Cinema of Kijū Yoshida takes place December 1-8 at Film at Lincoln Center.