For a movie about beautiful people living in beautiful homes in a beautiful neighborhood, Ang Lee‘s The Ice Storm is oppressively cold and eerie. Released in the fall of 1997 to critical acclaim, the film — despite its fine reviews and all-star cast — was a financial flop: it grossed a mere $8 million in the United States, a good deal less than an $18 million budget. Even more surprising, perhaps, was its lack of awards season recognition, failing to earn so much as a single Academy Award nomination. (Sigourney Weaver received a lone Golden Globe citation, for Best Supporting Actress.) This is peculiar, in part, because Lee had already established some goodwill with the Academy: two of his first three films — 1993’s The Wedding Banquet and 1994’s Eat Drink Man Woman — were nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, while his English-language debut, 1995’s Sense and Sensibility, earned seven nominations, winning one for Emma Thompson‘s adaptation of the Jane Austen novel.

However, it wouldn’t be until a handful of years later, with 2000’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, that Lee would at last earn his first personal Oscar nomination. And it’s a success he maintains to this day: five months ago, the helmer won a second Best Director Oscar, in this instance for his juggernaut adaptation of Life of Pi (Brokeback Mountain marked his first victory). From such a perspective, The Ice Storm is sort of a curious item in Lee’s filmography, a distinctly American film that somehow didn’t coincide with his breakthrough moment with domestic audiences. And, watching it today, the sardonic critique of upper-middle-class America seems a direct influence on American Beauty, the Sam Mendes-directed smash hit which took home several Academy Awards just a couple of years later — but something about The Ice Storm kept it from breaking through in the way Mendes’s film did.

The Criterion Collection did the film a good service when it released a two-disc DVD in 2008, and this week sees the debut of a Blu-ray upgrade. For a number of reasons, The Ice Storm represents a perfect item for home-video reappraisal: it was overlooked and under-seen at the time of its initial release; it remains a top-shelf work from a director whose international stature has continued to blossom in the years since; and many of the film’s young stars — their contributions every bit as important to the picture’s quality as that of their adult counterparts — have continued working to this day, giving the film a kind of retrospective interest for viewers who have seen that set gain prominence through the likes of Spider-Man, Batman Begins, and The Lord of the Rings. And the Blu-ray treatment, though I have not yet seen it myself, stands to do nothing but favors for the film’s plush spectrum of colors, which at once recalls both Douglas Sirk (in its heightened expressivity) and Yasujiro Ozu (in its meticulous attention to domestic detail).

As is the case with many Lee films, The Ice Storm is based on a source material of some renown: Rick Moody‘s 1994 novel. Set in 1973 in New Canaan, Connecticut, where Moody spent many of his formative childhood years, James Schamus‘s adapted screenplay is, in a big-picture sense, a faithful rendering of the Moody text. But a closer inspection reveals some critical distinctions between the two works. Moody’s chapters, for instance, are largely organized on a character basis, each one picking a single personality in the bunch to focus on. This is decidedly not the case with the film, as the script often juxtaposes simultaneous activity to reveal links between members of the ensemble. This is especially true of the ice-storm climax, which changes perspective constantly, enhancing the scope of the drama as well as the resonance of the story’s generational themes — which, in many ways, are more central to Lee’s film than they are to Moody’s text.

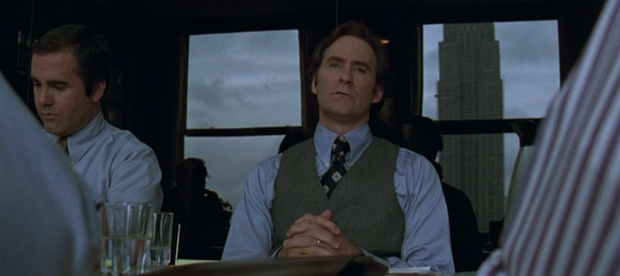

Another major distinguishing factor of Lee’s film comes through in the performances. In the book, Moody makes an exercise out of explaining how unattractive his characters are: Benjamin Hood has canker sores all over his mouth, and he’s been gaining weight for years, while his wife, Elena, is presented as an addict of academic journals, a glasses-wearing reading junkie who retreats to her library as frequently as possible. By contrast, the film complicates these characters by assigning them to movie stars: Kevin Kline‘s Ben Hood is a rather dapper, well-dressed, solid-looking guy, but Kline’s projection of Ben’s personality (his drunkenness, his infidelity) often makes the character appear complexly pathetic; Joan Allen‘s Elena, on the other hand, while meek and bookish-seeming, becomes surprisingly desirable in the film’s latter stages, as she transforms from cheated-on victim to agent of anarchy (her scenes with Jamey Sheridan are sublime).

Tobey Maguire — as Benjamin and Elena’s oldest child, Paul — presents an interesting challenge for the film, as his character actually turns out to be the book’s first-person narrator. Schamus and Lee confront this task slyly: the film begins with Maguire’s Paul, as he sits in a train that has been made immobile by the storm. He reads issues of The Fantastic Four to pass time, and much of his (otherwise occasional) voice-over is an analysis of the family turmoil facing these comic book characters. The other teenagers in the film all have their own means of escapism: when she’s not watching TV, Paul’s younger sister, Wendy (Christina Ricci), is engaging in all sorts of adolescent sexual activity; Mikey Carver (Elijah Wood) responds to Wendy’s advances, often meeting her in the woods to make-out; and Mikey’s younger brother, Sandy (Adam Hann-Byrd) — who harbors his own crush on Wendy — likes to explode his homemade airplanes on the family porch.

Such rebellious action of the offspring is mirrored in the parents, a potentially simplistic and familiar theme which attains a transcendent effect, here, because of the impending alienation that underscores events in the film. One afternoon, Elena sees Wendy riding her bike; minutes later, Wendy shoplifts some candy from a local pharmacy, an action that Elena herself will soon duplicate. While indulging in his affair with Janey Carver (Weaver), Benjamin scours the bathroom cabinets, and observes a mountain of prescription drugs; later, while trying to get close to Libbets Casey (Katie Holmes), Paul will also stumble upon cartons of pills. The resonance of these moments lies in the fact that the family members themselves — the very people who have so many innate things in common — despise each other, or, at the very least, rarely interact with one another in a meaningful, positive way. There is a hysterical scene in the film in which Benjamin tries to give his son a speech about the dangers of “self-abuse,” and Maguire’s reaction — pure jaw-dropped horror — is an exquisite illustration of Benjamin’s incompetence as a father.

The movie, which takes place over Thanksgiving break, is very much steeped in the America of 1973. A Watergate-era Richard Nixon is a fixture on the Hoods’ television set, which angers Wendy, who hates the man with a passion; this leads to a surreal image, in which Wendy dons a Point Break-style Nixon mask as Mikey starts to undress in front of her. Even more pertinent to the film, though, are the repercussions of the sexual revolution on the town of New Canaan. The film’s centerpiece sequence revolves around a “key party” attended by all the trendy couples in the area; the idea is that, at the end of the evening, the women take turns picking a random set of keys from a bowl, and then subsequently go home with whichever man owns the keys that they select. While Benjamin and Elena are dealing with that tension, their children are off attempting their own kind of sexual pursuit: Wendy gets drunk with Sandy, and then spends the night with him, and Paul does everything in his power to outdo his roommate (David Krumholtz) in the fight for Libbets’s affection.

When considered within the film’s atmosphere, these individual actions become tragic and even grandiose. Mychael Danna‘s score, with its antique flutes and chime-like bursts, is quite atypical, and lends a doomsday quality to even the most picturesque of the film’s brief New Canaan montages. Lee draws a brilliant visual parallel, too, between the ice storm and cubes that chill Benjamin’s vodka, with a few insert shots showing Benjamin emptying a fresh tray of ice, each one like a chink in the family’s armor. Lee and cinematographer Frederick Elmes, meanwhile, have a knack for locating simmering terror in the affluence of this Connecticut town; rare is the image in which one of the opulent neighborhood homes isn’t glimpsed through the brittle branches of late-November trees.

The greatness of the story’s concept — the concurrence of the historic, eponymous storm and the characters’ abhorrent behavior — comes from the feeling that these families are being pushed to the ultimate breaking point. On some level, these characters recognize the force of nature that is descending on their beloved town, and they use it as an excuse to do irrational, even inexcusable things. While the storm will test the town’s physical endurance, the characters’ behavior will test their own personal and familial stability. Benjamin gets profoundly drunk, and makes an idiot out of himself when he protests after Janey picks another man’s keys; Elena has sex with Janey’s husband in a car, while Benjamin sits on the floor of the bathroom, on the verge of passing out; Wendy continues flip-flopping between the Carver brothers, sleeping with Sandy while Mikey ventures out into the deadly storm. The town is going down, and these people are going down with it.

The burden of these events comes crashing down on Paul in a single shot, as the movie concludes, wordlessly, before the kid can even begin to process what has transpired over the course of the previous night. Whereas Moody ends his book by revealing Paul’s identity as the narrator, writing this text twenty years after the fact, Lee, in the film’s clinching gesture, doesn’t ask Paul to say anything. All we get is the character’s puzzled expression, as his father weeps behind the wheel of the frozen family car. It’s one of the most haunting final images of recent decades — as abrupt, concise, and perfect as the one that concludes No Country for Old Men. How will the family rebound from this night of disaster? How will they regroup, emotionally and physically? It’s an unanswerable question, which is exactly why The Ice Storm cuts to black on Maguire’s confused, bewildered face.

The Ice Storm Blu-ray is now available on The Criterion Collection.