“A cinematographer is a visual psychiatrist—moving an audience through a movie […] making them think the way you want them to think, painting pictures in the dark,” said the late, great Gordon Willis. As our year-end coverage continues, we must pay dues. From talented newcomers to seasoned professionals, we’ve rounded up the examples that have most impressed us this year.

28 Years Later (Anthony Dod Mantle)

This would earn placement sans knowledge of its production. Returning to the zombie wasteland more than two decades since the plainly revolutionary video textures of 28 Days Later, Danny Boyle and Anthony Dod Mantle composed their sequel to degrees largely more traditional and opulent—making all the more impressive that its main image-capture tool was an iPhone, adding a tessellated effect to many images and rendering more possible kill effects that are, frankly, just cool. As Mantle told me in an extended interview, “[For] Danny, it was a basic idea that this small tool––something that could be lying in the field 28 years later in Britain––could render images.” Excited though I am for next month’s sequel, I can already anticipate it’ll pale in comparison. Let’s hope Boyle and Mantle get to make this newfangled trilogy’s final installment and amaze us with something doubly unorthodox. – Nick N.

Afternoons of Solitude and Magellan (Artur Tort)

Artur Tort has fashioned a fresh wave of unflinchingly bleak and beautiful cinematography in 2025 that glows with the saturated violence of its subjects: colonizers and killers. Between Albert Serra’s Afternoons of Solitude (a disturbingly intimate documentary on the vulgarity and pride of the cruel and long-outdated tradition of Spanish bullfighting) and Lav Diaz’s Magellan (a pioneering and occupational epic ripe with extended duration and cameras that don’t move unless something is moving beneath them) the 35-year-old savant has more than proven his eye for lensing and framing in various styles and aspect ratios. He captures each film distinctly, but there’s a dense thematic through line that connects them in brutality and humanity’s fierce lust for power. – Luke H.

April (Arseni Khachaturan)

Shooting on the Arricam LT, primarily with an 18mm lens, cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan fashions two gazes in April—a mesmerizing film attuned to natural beauty and man-made terror. One embodies the mind of a heaving, otherworldly creature who looks at the world—the river during rainfall, poppies swaying in the breeze, a storm cascading in—as if for the very first time. The other hovers as it observes Nina in her stark, boxed-in existence, her panning, nightly cruises. Oftentimes Khachaturan will tinker with the focus, suddenly producing depth within any given frame so that the bokeh created by streetlights in the distance, the tension in her neck muscles during an autopsy, or a car getting stuck in the mud will quietly stun us. In April, every frame is a deliberate lesson in how to pay closer attention. – Nirris N.

The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire and Peter Hujar’s Day (Alex Ashe)

In experimental biopic The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire, Alex Ashe’s lush 16mm visuals meld seamlessly with an enveloping soundscape and diegetic music, creating a text that, while dense and intellectual, examines Césaire’s legacy in a firmly visual, experiential manner. In Peter Hujar’s Day, Ashe works to keep the single setting of Linda Rosenkrantz’s apartment from ever feeling too play-like, occasionally breaking the form of the interview setup, with posed portrait shots of Hujar (Ben Whishaw) and Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) that recall Hujar’s own photography practice. Through these two features, Ashe establishes himself as a fast-rising star in the 16mm cinematography world. – Caleb H.

Caught by the Tides (Nelson Yu Lik-wai, Éric Gautier)

One of the year’s stranger and more unique pleasures, Jia Zhangke’s Caught by the Tides weds over 20 years of footage from previously made and unmade Jia films led by one of the greatest actors of our time––who also happens to be his muse and wife––Zhao Tao. With a myriad of visual and aesthetic styles from regular collaborator Nelson Yu Lik-wai, with whom Jia started working in 2000, and Éric Gautier (DP on Ash Is Purest White), he makes use of the cinematographic scraps of his industry-topping DPs like they were always meant to be the first bites of the main course. – Luke H.

BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions (Bradford Young and others)

Considering the mixed-media approach of Kahlil Joseph’s kaleidoscopic, vigorous, engrossing feature debut BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions, the list of cinematographers whose work you see in the film would be near-endless (including Nickel Boys and All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt DP Jomo Fray, who worked on Raven Jackson’s contribution), but it is Bradford Young who is credited with the bulk of original footage. In charting the sprawling African diaspora, Joseph finds a through line with curator Funmilayo Akechukwu’s in-progress project The Resonance Field, imaginatively rendered here by Young and through the eyes of a journalist venturing into a futuristic vessel called the Nautica to cover the Transatlantic Biennale. It’s gorgeous, imaginative work that should be in conversation with some of the best sci-fi contributions to the medium of cinema this decade. – Jordan R.

Eephus (Greg Tango)

Shot in a naturalistic style that reflects the leisurely approach that the men take to their rec-league baseball game, Greg Tango’s first feature credit as cinematographer might not be showy in the traditional sense, but his camera deftly moves across the field, interested in nooks of the dilapidated dugouts and invoking the New England autumnal hues with a soft focus and long takes. His work accentuates Carson Lund’s nostalgic approach, the entire film suggesting a hazy memory. When the game moves into twilight and, finally, night, Tango obscures almost everything outside of the players and car headlights, making one understand that no matter how much the men might fight it, the passage of time is unstoppable. – Christian G.

Familiar Touch (Gabe Elder)

Sarah Friedland’s subtle debut about an octogenarian transitioning to Memory Care is as defined by Kathleen Chalfant’s unforgettable performance as it is by its soulful cinematography. Gabe Elder’s marvelously gentle approach overflows with tender frames—and fresh, warm, clear-eyed tones from colorist Ben Federman—that inch ever-closer to the mysteries, both painful and wonderful, of life’s precious end. Few cameras this year exude patience and love for their subjects as purely as Elder’s. It’s bound to launch the relatively new DP into coveted must-hire territory. – Luke H.

The Fishing Place (Rob Tregenza)

Marking quite a rarity, it might be the least-seen film on this list that has the year’s best cinematography. We’ve published two lengthy interviews with Béla Tarr and Alex Cox collaborator Rob Tregenza, one of which helped lead to the making of his latest directorial feature, The Fishing Place. On the surface this is a tale of faith and espionage in rural Norway circa World War II, but Tregenza takes the narrative to surprising places best left unspoiled. In also serving as cinematographer, Tregenza reinvigorates the very concept of the crane shot, using fluid movement and long takes to conjure an experiment that deconstructs the elemental powers of cinema. – Jordan R.

Grand Tour (Gui Liang, Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, Rui Poças)

Miguel Gomes’ postmodern travelogue also serves a “grand tour” of cinematographic styles, passing through Old Hollywood studio artifice, contemporary visual ethnography, and city symphony splendor. Working separately on location in East Asia and on a Portuguese soundstage, the trio of DPs flaunt their chops to the maximum, almost every shot offering up luxurious visual pleasure. Grand Tour’s lensing is terminally flashy––we feel how eager it is to impress––but also a real antidote to the sterile, compressed digital images defining mainstream and art cinema today. – David K.

It Was Just an Accident (Amin Jafari)

Although there’s evident skill and thought put into the compositions of the last decade of Jafar Panahi’s films, it’s impossible not to feel the limitations enforced on him by years of house arrest and forced mobile-phone filming. With the help of Amin Jafari––his cinematographer since 2018’s 3 Faces––Panahi finally breaks free; his camera glides around and through a car in the opening scene, zooming into a group of people pushing the vehicle through a crowded street. Their increased capability for unique angles and lighting is crucial to Accident‘s overwhelming power, up until the final shot. – Devan S.

The Love That Remains (Hlynur Pálmason)

Meticulous writer, director, and cinematographer of his own features, Hlynur Pálmason, has made a name for himself with his meditative, homegrown, community-based approach to filmmaking in Iceland. Shooting where he lives with the people he lives with and around, and in multiple short production phases (sometimes only getting one shot) over the years—so as to bake time in to consider, reconsider, and find new inspiration—Pálmason is one-of-a-kind. There’s a strict, contemplative composure to his near-square frames, textured 35mm aesthetic, experimental exercises (one of which got their own feature spin-off in Joan of Arc), and still cameras. The Love That Remains is arguably the best film of the year, a Malickian departure from his past work that heralds a new Pálmason. – Luke H.

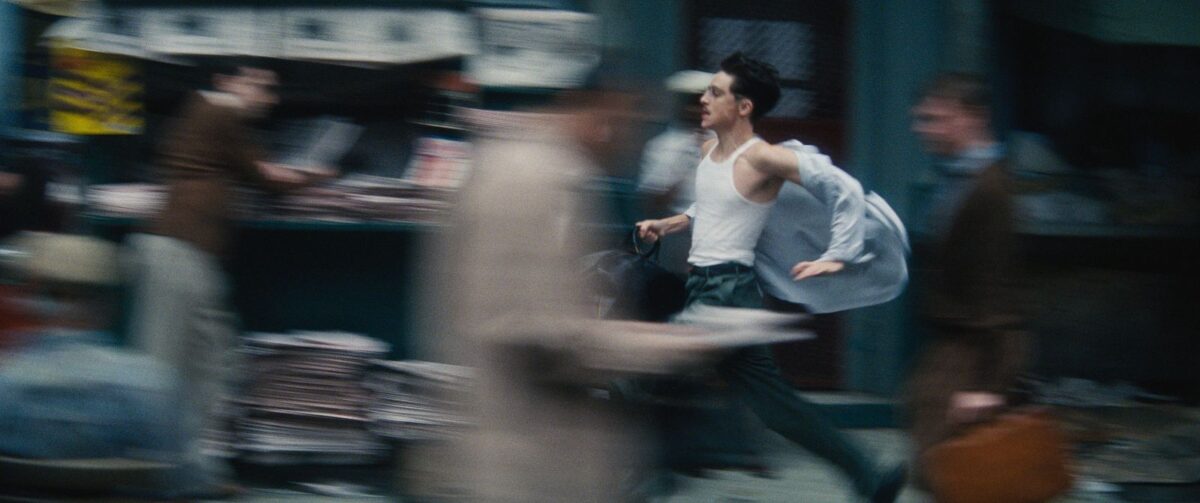

Marty Supreme, Eddington, and Mickey 17 (Darius Khondji)

If we were giving an award for the most varied cinematography of the year, it would surely go to Darius Khondji, who has lensed a trio of vastly different projects. From capturing the comic sci-fi wonders of Bong Joon Ho’s Mickey 17 to approaching the western with bracing immediacy in Ari Aster’s Eddington to, in his finest achievement of the year, shooting the frenzied journey of Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme with a sense of kinetic grace, the Iranian-French cinematographer proves he is one of the greatest artists working in the medium today. Be sure to stay tuned for my chat with Khondji ahead of Supreme‘s release. – Jordan R.

The Mastermind (Christopher Blauvelt)

Kelly Reichardt first worked with Christopher Blauvelt in 2010 on Meek’s Cutoff, and she’s never looked back. The Mastermind marks their sixth feature together and proves the collaboration is only getting stronger. In a marked departure from past work (consider the natural vibrance of the similarly located First Cow), their film about a bored, hapless husband who resorts to art thievery for a kick––much to his remorse––takes on a barren, cheerless Northeastern gray. With unsaturated color and a pervasive silhouetting glow that would make Llewyn Davis proud, Blauvelt plays perfectly into the dour mood of Reichardt’s screenplay. – Luke H.

No Other Choice (Kim Woo-hyung)

Cinematographer Kim Woo-hyung proves a perfect match for Park Chan-wook’s technical precision and penchant for showiness, and their resulting collaboration dances between comedy and thriller elements with ease. It all feels so effortless that Park and Kim have extra time to craft playful match cuts and present technology, like scrolling or texting, on screen in such an inventive manner, immediately rendering all other cinematic attempts as embarrassingly dated. “The best make it look easy” is an adage which applies to Park and Kim’s work here, leaving one to often think, “Of course that’s the only way they could’ve framed such a complicated sequence.” – Caleb H.

No Sleep Till (Sylvain Marco Froidevaux)

For her feature debut, French-American Alexandra Simpson enlists her Swiss film school compatriot Sylvain Froidevaux to lend a European eye to her nostalgia-tinged look at a disappearing Florida under threat from both development and weather. Shot on Sony prosumer cameras with Zeiss super speed lenses (a combination engineered for low-light conditions on a tight budget), No Sleep Till is full of memorable locations, all rendered to elicit a feeling of longing in the audience. Where the film really shines, however, is its framing of bodies, which recalls the photography of William Eggleston, a reference point for Simpson and Froidevaux. No Sleep Till proves a micro-sized budget is never an excuse for sloppy images. – Caleb H.

One Battle After Another (Michael Bauman)

From Chief Lighting Technician and Gaffer extraordinaire (with credits like Training Day, Munich, Iron Man, The Bling Ring, and Good Night, and Good Luck to his name) to co-DP alongside his boss and regular collaborator Paul Thomas Anderson on Licorice Pizza, to One Battle After Another––his first official solo DP credit on a feature––Michael Bauman has skyrocketed into significance through his work on PTA films, which began in 2012 with The Master. Hitting various new aesthetic highs in OBAA, Bauman’s silvery VistaVision camerawork (courtesy of Giovanni Ribisi) shines in too many sequences to name here, chief among them the floating rollercoaster framing of ever-dipping and -rising asphalt, the contrasting wide and tight lensing of revolutionaries in-action and on-the-run, and the winding oners that ground the story’s gutbusting goose chase. – Luke H.

Rebuilding (Alfonso Herrera Salcedo)

Though shot digitally, the textured quality of cinematographer Alfonso Herrera Salcedo’s work on Rebuilding almost feels like it was pulled off on film. As Josh O’Connor and the ensemble are captured across the vast expanses of the San Luis Valley in Colorado, DP and director Max Walker-Silverman convey an overwhelming sense of aching beauty. This is a character searching for purpose as one small piece in the tapestry of nature that can turn destructive at a moment’s notice, continuing to rebuild a life so he can bask in its wonders. – Jordan R.

Reflection in a Dead Diamond (Manuel Dacosse)

Just as our hopes for movies to look like movies begin to circle the drain, director of photography Manu Dacosse offers a rush of analog flair. Every 16mm frame of Reflections in a Dead Diamond is lush and bursting with color. Its photochemical format and saturated color-grading underscore Hélène Cattet & Bruno Forzani’s commitment to a real-deal impressionistic take on the Bond-sploitation Eurospy films of the 1960s, many of which were shot in glorious Technicolor. With more compositional tricks up their sleeves than Q Branch, it’s a true feat that the camera department got this done in 39 days when you add up the extreme close-ups and insert shots. Masterful and fun is how these movies should feel. – Kent M. W.

Resurrection (Dong Jingsong)

Oners have become Bi Gan’s signature. 45 minutes in Kaili Blues; an hour (and 3D) in Long Day’s Journey Into Night. For Resurrection, it’s a half-hour New Year’s Eve tour de force that starts with waterfront fireworks, travels through alleyways and nightclubs, violence escalating until dawn breaks. The director worked here and on Journey with cinematographer Dong Jingsong, who brought a similarly saturated color palette to The Wild Goose Lake. The camerawork slides from silent film techniques to sci-fi, each era marked by an assured exuberance even when the narrative is impenetrable. – Daniel E.

The Secret Agent (Evgenia Alexandrova)

The Secret Agent’s sun-dipped, dry, clear palette makes blood look radioactive when it spills out of the people who get shot, gouged, stabbed, and blasted. This isn’t an overtly violent film, but when it is, it is absolutely pulse-pounding. Evgenia Alexandrova’s close-ups and tracking shots work with the editing to keep tension high even in sequences where there is no danger. The slow zooms into faces, the claustrophobia of conversations in hushed tones or brutish grunts speak to a Brazil where being too loud could get you in trouble at any moment. The camera is constantly aware of its surroundings while cutting them out of the frame. – Soham G.

The Shrouds (Douglas Koch)

You can’t overlook David Cronenberg’s key below-the-line team: from production designer Carol Spier to crack composer Howard Shore, and, until recently, DoP Peter Suschitzky. Taking up Suschitzky’s forbidding mantle on Crimes of the Future and now The Shrouds, Douglas Koch’s noir-inspired lighting for each goes a long way to setting their funereal, yet emotionally warm atmosphere. Spanning the cavernous interiors of protagonist Karsh’s (Vincent Cassel) workplace and homes, to the intuitive way he lights the film’s sundry “second screens,” his work is a perfect visual container for some of Cronenberg’s most intellectually piercing ideas. – David K.

Sinners (Autumn Durald Arkapaw)

Much has been made of the aspect ratio shift that kicks off Sinners’ gory finale. But Autumn Durald Arkapaw’s cinematography is more than just (admittedly great) gimmicks. There’s the beauty of the fields in the daylight, the bright lights of the Juke Joint at night; there are those two musical sequences, with their swirling camera moves, that will be talked about for years. Most importantly, there’s the excellent use of not just shadows but the night itself to provide Sinners’ excellent atmosphere, taking full advantage of the IMAX screen and warmth of film grain. – Devan S.

Read our interview with Autumn Durald Arkapaw on Sinners.

Sirāt (Mauro Herce)

Move over Dune(s)—there’s a new desert movie to mark the 2020s. Mauro Herce’s gritty, tenacious visual aesthetic is so comparatively desolate (there is no “spice” equivalent, much less water or hope, in the deserts of Southern Morocco) that it renders Arrakis the less-grim and godforsaken setting. Oscillating between deep, purpley blues, golden-hour oranges, and unsaturated daylight brights, Herce’s cinematography––and sixth sense for framing dusty music equipment against arid landscapes––lends Sirāt a propulsion that simply can’t be unfelt once all’s said and done. – Luke H.

The Testament of Ann Lee (William Rexer)

“We approached it not looking like a traditional musical,” cinematographer William Rexer noted in a recent interview. “We approached it like a Baroque painting. Those were our references, paintings, not really any movies.” Many films take this approach; few risk putting the paintings themselves onscreen to compare. Yet Rexer’s lighting, informed by candles and what little sun 18th-century Englands Old and New allow, earns the inspiration, and blurs the line between them. Its subjects, especially star Amanda Seyfried, seem to illuminate the charcoal shadows from which they sing for salvation, setting aglow the celluloid Rexer spins through the camera. – Scott N.

Train Dreams (Adolpho Veloso)

Any film shot in roving takes across natural landscapes is bound to invoke Terrence Malick’s name, but Adolpho Veloso’s work in Train Dreams differentiates itself by showcasing the destruction of nature by man. Using a 3:20 aspect ratio that pushes your perspective up and down, his camera is keenly interested in the humans at the center of this story, boxing their faces into the frame. Announcing themselves with a dizzying shot of a tree being cut down—filmed from the perspective of the tree—Veloso and director Clint Bentley wisely juxtapose Robert Grainer’s innate goodness with the ruination of forests that he’s part of. Shot with naturalistic light, it’s a profoundly beautiful film but also one that puts that beauty in conversation with its themes. – Christian G.

Read our interview with Adolpho Veloso on Train Dreams.

Viet and Nam (Son Doan)

The stillness with which Son Daon lingers on tender moments makes them feel like eternal portraits of their characters. In one sex sequence in a coal mine, the lighting provides harsh shadows, illuminating the skin, its sweat, its dirt, with the figures almost in a void, the world disappeared around them. The rest of the film frames almost everything in still shots, except for one exceptional sequence tracking across a field where soldiers hold position. The camera scans evidence of violence in the film that disrupts its central romance in startling ways. – Soham G.

Who by Fire (Balthazar Lab)

With unforgettable, long-developing shots that traverse stretched out dinner tables, rich natural landscapes, slate-gray roads, and dark, wooden rooms (not to mention the entirety of the B-52s’ “Rock Lobster”) Balthazar Lab’s cinematography on Philippe Lesage’s sleeper great stands out among the film’s most impressive characteristics. Lab’s immaculate eye is matched only by his sensibility for duration. Under Lab, the stunning cool-hued gleam of the woods swallows the many characters stuck in them. Even in the shadowed warmth of the cabin, there’s a coldness to Lab’s work––the kind that reflects the bitterness of young love, complicated pasts, and iced-over drama that finally cracks. – Luke H.

Honorable Mentions

- Below the Clouds

- Black Bag and Presence

- Blue Sun Palace

- Bugonia

- The Chronology of Water

- F1

- Father Mother Sister Brother

- Happyend

- Hamnet

- If I Had Legs I’d Kick You

- Misericordia

- Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning

- Nouvelle Vague

- On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

- The Phoenician Scheme

- Sister Midnight

- Sound of Falling

- The Smashing Machine

- The Sparrow in the Chimney

- Urchin

- Weapons