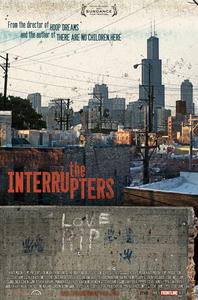

Steve James’ dense, meticulously-focused documentary, The Interrupters, about urban violence in Chicago and those who’ve chosen to prevent it is an epic chronicle of American gang warfare determined to show the good in every devil and the latent evil in every angel.

Running at almost 3 hours, James refuses to commercialize his subject. The subject is Ceasefire, a Chicago-based group of ex-gangbangers and gang leaders who now work as violence interrupters, walking the streets of Chicago in an attempt to convince gang members to give up the criminal lifestyle and instead make less money and wield less power on the streets.

Tio Hardiman, the director of Ceasefire, is completely aware of the difficulty of such a proposition, as are most of the interrupters. It’s this uncommon amount of honesty that allows James to get up close and personal into a world most are just as easy forgetting about. There’s Lil Mikey Davis, an interrupter who went to prison for robbing a bank at gunpoint years earlier as a teenager. James follows Davis back to the bank to apologize to the employees who were there on that day. It’s a harrowing moment, so real it feels almost fake.

Then there’s Caprysha Anderson, a young, angry girl with an absentee, drug-addicted mother. Her only real hope is Ameena Matthews (shown above, in the middle), the daughter of legendary gang leader Jeff Fort, who roams the city streets preaching peace to those willing, and unwilling, to listen. She emerges as the true hero of the film, blindly convinced she can convince these young gang members there is another way.

Not unlike the HBO crime saga The Wire, James’ doc starts simply enough, presenting the conflict and jumping into what seems to be the solution. Then everything becomes more and more difficult. Things get entangled, answers aren’t so easy. We see that these interrupters aren’t all convinced they’ve made the right decision. It’s a dangerous job for not much money. A young interrupter earns a gunshot wound halfway through the film, and Hardiman can barely look at the young man without crying. Interrupters like Cobe Williams live with the sins of the past, making small change after small change in the name of the future.

But nothing’s easy, and James wants everyone to know as much. A particular scene in which Cobe gets two sons, members of opposing gangs, to meet with their mother after she’d ran from home months earlier, officially giving up on her boys, ends with a whimper than a bang. The victory winds up being the meeting itself more than any kind of resolution or dynamic change.

This isn’t Hoop Dreams. There’s no clear goal, no clear ending. Watching three hours of maybe is no easy task. There are no flash stat charts, no montages. It’s the camera, the criminals and the ex-criminals. We never see outside of this world. We’re in it, good and bad. James wants us to see the depths of the street game, even if he’s not sure how deep it takes to get to the bottom.