Sharks have been lurking in the depths of our cultural consciousness for decades now. From the fear that Jaws instilled in audiences in 1975 to the endless consumption of bogus Shark Week docufiction that Discovery Channel peddled, there has been a sense of terror around these unique creatures that few have tried to truly dissipate.

To look at Valerie Taylor’s best known film works, including Jaws and Blue Water, White Death, one might believe the diver and photographer to be one such perpetrator of these myths. But Sally Aitken’s documentary Playing With Sharks offers an in-depth look at the way Taylor (and her husband Ron) dedicated her life to showcasing the beauty of the ocean’s most misunderstood creatures.

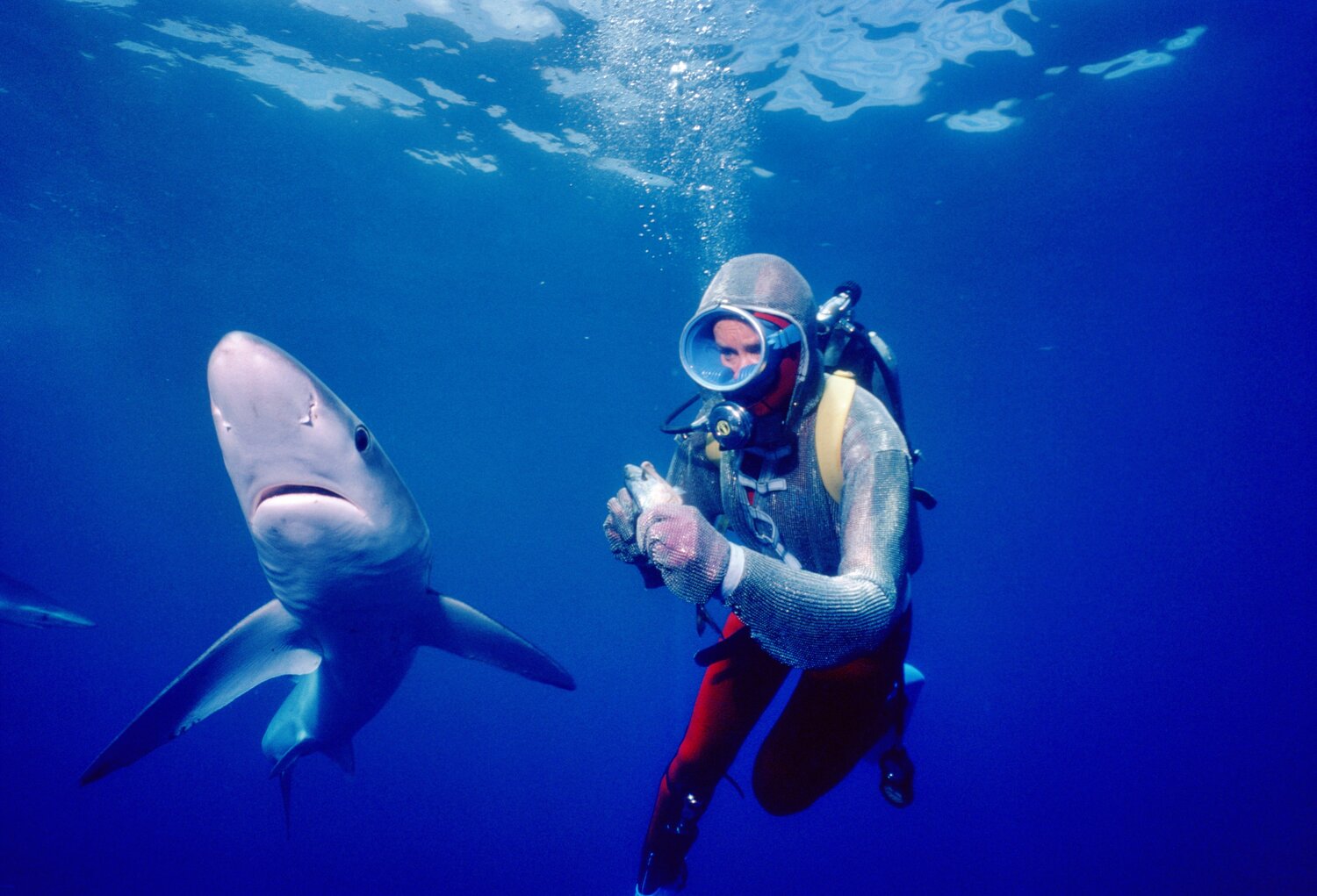

As Taylor herself jokes, she often appeared as something of a Bond girl through the lens of her husband’s cameras and the perspective of the audience that witnessed their documentaries. A woman who was at the top of the competitive spear-fishing game easily caught attention, but the Taylor’s grew to loathe harming that which inhabited the ocean they so loved.

The pivot from hunting to photography and Valerie Taylor navigating her guilt is one of the film’s most interesting aspects, reflecting on how one makes up for the lives they’ve taken. This question builds throughout the documentary as more details are revealed about the way the diver dedicated her life to protecting the sharks that she studied and photographed. There is no abundant sentimentality to be found here, thankfully; even her frustration at fisherman slicing off shark fins or gutting them for sport seemingly fueled more by anger than heartache and contextualized by her dedication to conservation.

Aitken is much more interested in using the wealth of footage that Taylor and her husband shot over decades of working together to highlight her accomplishments and prove that sharks are more akin to dogs than any bloodthirsty monstrosity. The gorgeous collection of film and photographs that makes up most of Playing With Sharks, guided mostly by its subject narrating her experiences, are engaging and often delightful. There’s as much joy in how she presents her experiences shooting everything for Jaws at half-scale to emphasize Spielberg’s unnaturally sized great white shark as fondly as she recites an amusing anecdote that shows her conditioning a shark via Pavlovian food experiment in order to get the perfect shot of it swimming above a reef.

What few talking heads there are don’t distract from the wonderful assemblage of footage and, in fact, mostly serve to complement Valerie Taylor’s achievements, experiments, and wondrous tales. Even when Aitken’s cuts in unnecessary and repetitive graphics of a lens emphasizing a reel of photographs, it’s Taylor’s personality that grounds the film and makes its 90 minute length breeze by. Her presence, her voice, her trademark look (if Cousteau had the red beanie, Taylor had her red ribbon pulling back a blonde ponytail), and her willingness to dive headfirst into things that most individuals would find flat out dangerous, is irresistable.

Her consistency as an individual makes the shifts from her films to the contemporary footage of her life as it is currently less jarring. There is a naturalism and familiarity to the way Taylor’s friends and husband captured her and the ocean they spent their life exploring and Aitken takes great measures to make her own footage feel as casual. Playing With Sharks could have easily been another documentary heaping praise onto an individual, but it works so well because it allows its subject to engage with her greatest regrets as much as her greatest achievements.

Playing With Sharks premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.