On the surface, Jonathan Ames’ You Were Never Really Here seems like an odd fit as source material for a film by Lynne Ramsay. Ames’ novella is a pulpy genre exercise about a hard-bitten vigilante, one of those lone-wolf types who abides by a strict code of ethics and practices his chosen métier with fanatic professionalism. It’s the kind of character that usually appeals to macho filmmakers such as Jean-Pierre Melville or Walter Hill, not to a poetic feminist of Ramsay’s kind. Unsurprisingly, she’s appropriated the material for her own purpose, paring down the already slender narrative and plunging deep into the tortured psychology of its protagonist. The results are breathtaking, and You Were Never Really Here stands alongside Claire Denis’ Bastards as one of the most ferocious indictments of systematic abuse of power and gender violence ever projected on a screen.

The correlation with Bastards is more than superficial and likely intentional, as Ramsay tweaked Ames’ original story, strengthening the narrative parallels by changing details of a character’s suicide and incorporating an incest angle. Unlike Denis’ protagonist, however, Ramsay’s did not stumble upon a world of sexual violence and teenage prostitution unawares. Joe (Joaquin Phoenix), a hired gun who specializes in rescuing underage girls from sex slavery, was born and bred in violence: the trauma of growing up in an abusive household was later compounded by two scarring incidents during his time in the Marines and the FBI. These experiences, which are related throughout the film in fragmentary flashbacks that haunt Joe’s everyday, have left him a shell of a man harboring a burning death wish.

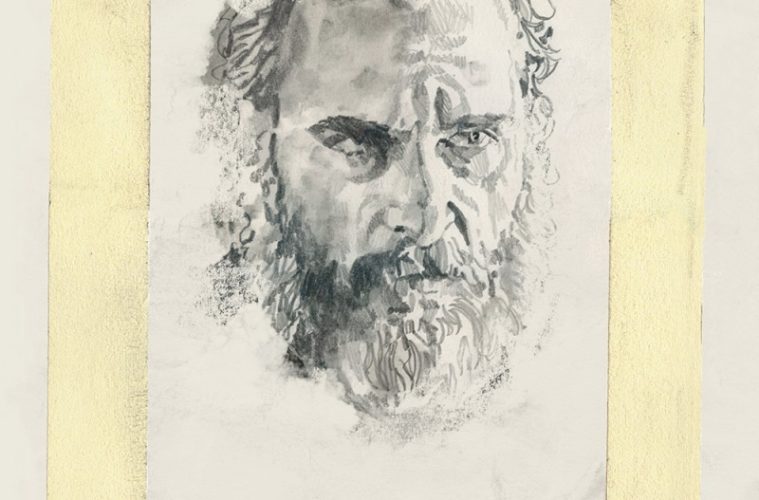

Without ever needing to overact, Phoenix manages to convey his character’s devastated interiority through sheer physicality, his hulking demeanor and ravaged countenance bearing the weight of his traumatic past. Phoenix’s performance is exceptional in its combination of delicacy and vehemence. By turns tender and barbaric, he renders Joe a virtuous man whose inability to prevent the victimization of women, first at home and then in his different professions, has brought him to the brink of madness. When his latest job goes wrong, it pushes him past his breaking point, and the film follows his fevered mission to retrieve the 13-year-old girl he failed to rescue and get his revenge on the men who deceived him.

On the level of montage, You Were Never Really Here is an expressionistic tour de force. Ramsay and her editor Joe Bini splinter the film’s chronology through a masterful use of jump and hard cuts, charging Joe’s rush across the city with a manic propulsive energy that reflects his frenzied state of mind, which is progressively exacerbated by an accumulation of physical injuries and copious intake of painkillers. Jonny Greenwood, the film’s composer, must have been closely involved in the editing process, as his terrific soundtrack is in perfect synergy with the rhythm of the montage, not only injecting the narrative with further urgency, but also augmenting each scene’s emotional nuance and intensity.

Although the level of violence and gore is extreme, it never feels unjustified or gratuitous. Ramsay also peppers the film with lyrical touches, finding moments of transcendental beauty amongst all the ugliness: a corpse wrapped in plastic sinks to the bottom of a lake and a long, golden strand of hair floats out behind it, leaving a trail like an ethereal apparition; two men lie bloodied on the floor, holding hands and singing a delicate tune as one of them draws his final breaths. These touches prevent the film from succumbing to misanthropic despair. After all the carnage and misery, Ramsay does allow for the possibility of redemption. When she closes her film with a character saying, “It’s a beautiful day,” the line doesn’t come off as cynical, but as a desperately earnest plea.

You Were Never Really Here premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on April 6. See our coverage below.