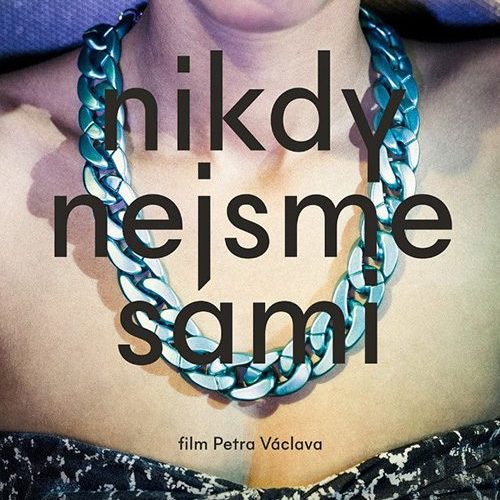

Fans of Quentin Dupieux should rejoice because I haven’t seen a film this absurdly hilarious since Wrong. Petr Václav‘s We Are Never Alone is definitely bleaker, darker, and strangely realist, but it has that same sense of subtle humor to give you pause about the meaning of what’s thus far been viewed. The story concerns two families with certifiably insane patriarchs, a local pimp searching for escape, and the whore he deludes himself into thinking loves him despite her pining over the father of her daughter in jail. They each have their own personal problems that should be uniquely particular to their individual psychological imperfections and yet when they converge they’re insanely revealed to be kindred spirits spinning around atop this cesspool we call Earth.

Václav includes political commentary about the current state of affairs in Czech Republic (don’t tell Miroslav Hanus‘ prison guard he’s a communist, though, he just hoped the results of the overthrow turned out better than it has) alongside some existential crisis-inducing fear for health (Karel Roden as a hypochondriac drama queen who may be in tears more than not), safety (Hanus’ belief that former prisoners will murder him in his sleep inspires his young son to daily kill incrementally larger animals and leave them dead by the gate as “warnings”), and love (Roden’s wife played by Lenka Vlasáková is drowning in enough familial strife and boredom to declare her affection for Zdenek Godla‘s pimp despite never speaking to him more than, “Here’s your change” at the convenience store).

Sound like this would be up your alley? Make sure it does because, like with Dupieux’s oeuvre, We Are Never Alone will either hit your funny bone or leave you completely numb and looking for your money back. I enjoyed it for the most part, especially its surprisingly violent and macabre finale seeing tiny white lies and huge displays of rebellion opening up rabbit holes that can’t resolve with anything other than death. No one is normal—except maybe Hanus’ wife who disappears after sneaking her son some loose change to buy a candy bar while hubby was preoccupied talking about a “new war” to come with Roden—and thus no one is predictable. Morality and empathy are non-existent as Václav’s nihilistic bent renders compassion a dangerous liability.

It’s tough to talk about any interactions considering their surface machinations hide a complex series of details that infer upon the meandering plot in crucial ways. You really do have to see to believe because a stoic character like Vlasáková’s father (played by Rudolf Triska) will reveal himself to be larger than the visual punch line we assumed he was. His presence gives Roden one more reason to go into hysterics (the man hates him), but his coldness towards his daughter and grandkids also cements his fate and theirs in the process. Someone like Klaudia Dudová‘s prostitute is seemingly additional color for scowls of jealousy and welcome sass lobbed Godla’s way, but even her actions—no matter how small—are integral to where the others travel.

So instead I’ll merely shine a light on the wonderfully eclectic performances. I do believe Roden played comically idiosyncratic before (Was it 15 Minutes?), but seeing him here still screwed with my head because of the arch villains he has portrayed since. It wasn’t until the movie was half over that I went from “this guy looks like Karel Roden” to “I think that is Karel Roden.” He is so over-the-top and exaggerated that it should feel out of place in an otherwise reserved dramedy, but it works exactly because of the contrast. His need to touch his wife for solace plays brilliantly against Vlasáková’s disgust-driven recoils and his crazed banter can only be diffused by Hanus’ extreme deadpan severity supplying possible solutions rather than eye-rolls of frustration.

Hanus is unreal with a blank slate gaze and robotically routine movements somehow never feeling bland, behavior like having to unlock his son from his room for a glass of water is absurd enough to make his over-zealous mechanics comical in their dryness. Godla’s penchant for waffling between hardened mad man and sensitive lover make him more sympathetic than he probably should, his desire to not be alone proving stronger than his tastes. And Vlasáková ultimately steals the whole movie with her inability to cope in a life she’s out-grown. She is defined by screams of agony when the family suffocates her and excited smiles when a new career path opens at Godla’s brothel. She becomes the only character moving forward with happiness despite her choices seeming otherwise.

I’m still attempting to wrap my head around Vlasáková’s place in the bigger picture outside of relationships with Godla and Roden, though, namely Václav’s decision to change from black and white to color twice with her as catalyst. At least I think each instance coincides with Vlasáková’s distraught housewife—maybe her admitting to wanting more, her sense of rejection, and then her second chance? I don’t know. Maybe Václav merely thought the shift would draw us in aesthetically and it’s not steeped in context. Either way this visual alteration is but one of numerous odd details that seem only marginally less odd when put together with the rest. I’m not sure this caustic tragedy appeals for repeated viewings, but I’m sure glad I saw it at least once.

We Are Never Alone is currently playing at the Toronto International Film Festival.