Rob Zombie’s films always strike up controversy; not the kind that’s associated with politics like polemical documentaries, or what the genre he operates in, horror, do because of their often graphic sexuality and violence. Rather, his work divides because they bear the mark of a distinct sensibility. The sensibility containing a bevy of influences; dad rock, early horror, music videos, 70s American new wave, etc. But while homaging long past-modern works can often strike acclaim, there lies a beating heart of originality in Zombie’s work. The Lords of Salem reveals his true intent; to celebrate the images of horror and cast a self-aware light on them.

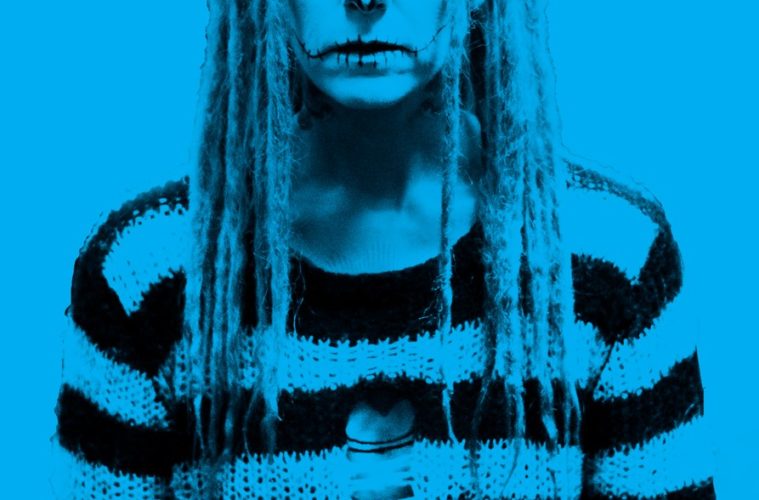

The story is simple enough. Beginning with a prologue of witches doing their usual witch business in the 1700s, the narrative shifts to modern-day Salem, Massachusetts. Our lead, Heidi, is predictably played by Zombie’s real wife Sherri Moon (turning in a surprisingly solid turn) who happens to be one-third of a DJ trio. One night they receive an album strangely presented in a wooden box. They play it on the air and its sludge/doom/art metal sound (to be honest, it was like something I’d actually listen to) seems to summon something strange that will haunt Heidi over the film’s title-card enabled structure of Monday – Friday.

While Zombie’s previous films belonged more to the slasher and exploitation subgenres of horror, The Lords of Salem operates more in the Rosemary’s Baby/The Sentinel mold. Those two films were about the psychological terror experienced by a female, much of which occurs within an interior space. Thus this being an area that allows more for a slow-burn that dips heavily into surrealism as opposed to gore. Essentially, this gives him the opportunity to exhibit his formal skill, weaving through the influences mentioned in previous paragraphs to create an atmosphere of dread and, at times, comedy.

What’s remarkable though is how much Zombie’s mise-en-scene displays an abnormal fascination with artifice. Like the best image in Halloween 2; projections of classic horror films being cast over a barn at an outdoor party, artwork including some from Melies’ A Voyage to the Moon adorns Heidi’s apartment. Connecting this is the execution of many of the actual horror elements; the monsters haunting many of Heidi’s vision, although often shrouded in darkness, harken back to man-in-suit effects. Add to that, Zombie nears the end creates grand widescreen compositions backed by classic music, its inherent insistent nature recalling Kubrick taking on a strange presence in a horror film like this, meaning that it can only be somewhat ironic.

If anything, Zombie’s contrarian nature is revealed. Consider that our DJ protagonist feels like one of the few outputs of culture in a gray, cold northern town. Zombie himself grew up in similar surroundings, and extends his rock-star rebellion to his films. He took a slasher franchise and made a clear attempt to elevate it to an unrelentingly grim character study, but this time he confronts horror with more of a sense of humor, even if the end result is happy for no one.