Making a film about a tragedy like the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami should never be taken lightly. With over 230,000 people dead in fourteen countries, the entire world was affected by this devastating event made worse due to its untimely December 26th date. An attempt to convey the emotions, pain, and hope hidden within could easily fall into manipulative territory, missing the point to become an exploitative moneymaking endeavor. So, it was with a skeptical soul that I went to the world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival—unsure if I could look past the stigma to accept the work as a heartfelt eulogy rather than a shameless attempt at manufacturing grief and sorrow for the wrong motivations.

But when that first wave hit to turn The Impossible‘s central family’s universe upside down, I realized writer Sergio G. Sánchez and director Juan Antonio Bayona had their hearts in the right place. This would be more than simply a European, white family trying to survive amidst the indigenous Asians dying in the water. It is a powerful recreation of not only the awe-inspiring destruction wrought but also the battlefield of the soul to find the strength to keep moving forward. Humanity’s never wavering spirit for life and our capacity to be humble and giving in the face of tragedy is put on display as regular people rise to the occasion. At a time like this, mankind itself becomes your family—to look out for you and to need your love and compassion to carry on.

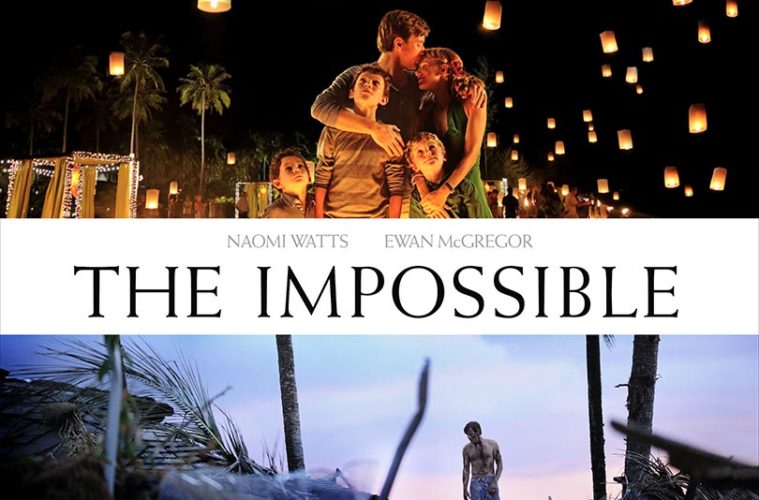

Opening on Henry (Ewan McGregor) and Maria (Naomi Watts) as they take their three kids on vacation to the Orchid Beach Hotel in Phang Nga, Thailand, it’s understandable for skepticism to seep in. Here is this well-to-do family living in Japan because of his job—a job so financially sound that her doctoral degree can lay unused while there—deciding to spend the holidays on the beach. Landing on the 24th, the kids receive a fun Christmas of toys and sun only mired by the grown-ups discussing whether or not they’ve overstayed their Pacific Ocean welcome and should return home to Europe. Before conversational headway can be made and just when Henry goes to play with his boys by the pool, the first wall of water crests above the palm trees and crashes down.

What allows viewers to look past the very Anglo-slant is the knowledge that this is a true story. Clichés, contrivances, heartstring tugs—it all happened. This story is a film producer’s ideal dream including everything we’d accuse a fictional account of manipulation for and makes it all not only acceptable, but relevant. As Mom and eldest son Lucas (Tom Holland) find each other in the current and Dad retrieves Simon (Oaklee Pendergast) and Thomas (Samuel Joslin) holding onto trees for dear life, their divergent paths towards the hospital and survivor camp respectively contain the sort of coincidental overlapping only fate can provide. Instead of rolling your eyes, though, you’ll find yourself holding your breathe through the suspenseful search to reunite and bask in the joy of escaping death—at least for now.

Between the family getting separated more than once; Maria’s leg being torn to shreds and at risk of infection; and three young boys often left to fend for themselves inside this nightmare, Bayona has many opportunities to raise the stakes and amp up the suspense. The computer effects and art direction is authentic to a fault as the sets must have been massive during production. Watching Watts and Holland drifting through water so high you can only see the tops of trees is a harrowing experience; following McGregor to the overflowing hospitals around the city a difficult search. There are hundreds of extras motionless, screaming, writhing, and trying to hold on to life out by the fringes and Bayona fearlessly shows the carnage without filter to achieve maximum impact.

And while there are glimmers of hope—like the periphery tale of a young boy named Daniel—we must helplessly sit back and accept the overhead shots of body bags and the decreasing health of Watts as she waits to possess enough blood for surgery. There’s young Pendergast acting as precious as can be, unaware of quite what’s happening; Joslin’s only marginally older brother left with the responsibility of caretaker while McGregor looks for the others; and Ewan sharing some heartbreaking moments in complete surrender to his emotions that will destroy you. But it is Holland who steals the show when left to process the death around him with only his bed-ridden mother to ground him in a sense of reality. His evolution from spoiled brat to hero excels through a believably pained performance.

Acting aside, The Impossible is very much a document of this tragedy beyond one family. They’re our entry point to see the chaos through their eyes, but the film’s most memorable feat is Bayona’s visually stunning sequence inside a cyclone of water consuming everything in its path. Above moments of humility, futility, optimism, and faith is a final act of Mother Nature’s power catching us in the current with Watts. We’re spun and dragged alongside her as branches stab, objects crush, and oxygen disappears. To think this gorgeously brutal scene was the last many experienced before leaving this earth is a tough concept to swallow and makes the end to Henry and Maria’s journey obsolete. This is the moment of true horror and tragedy that allows the film to be an almost unendurable portrait of those we lost.

The Impossible is screening at TIFF and arrives in theaters on December 21st.