Some people can’t help themselves from striving to be the best whether that means winning a contest, getting a promotion, earning accolades, or proving you’re the only one able to accomplish an impossible task. They want to be relied upon for results. Radu (Tudor Istodor) is all the above. Doing what he’s told isn’t enough — he looks beyond what’s asked to discover what’s needed. And when it comes to career this character trait has served him well. He possesses the connections, intelligence, and skills to operate in Romania as a “fixer” and believes those attributes assist his aspirations to become a journalist. But somewhere along the line he discovers how gray the area is in which he excels. Suddenly his bullish insistence takes on an air of exploitation.

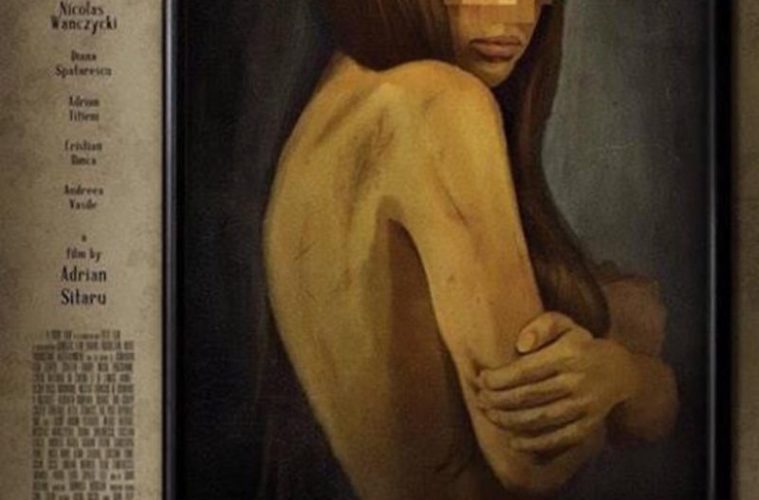

Director Adrian Sitaru‘s The Fixer is a story about this realization, Radu’s return to old connections after he put them behind him for a new life with Carmen (Andreea Vasile) and her young son Matei. He’s now a trainee working for the publication employing her — cognizant of the ropes and what’s needed to acquire an exclusive, but not quite able to do so on his own. This is why a news break concerning two repatriated minors from France, kidnapped into prostitution by a renowned pimp, is assigned to Carmen once he and his boss strike out with the police to interview fourteen-year old Anca (Diana Spatarescu). Knowing Radu has a cousin with political influence where the church is concerned, however, Carmen turns to him for help.

He knows it could have been his story. It should have been. So he talks with his cousin, works magic to give Carmen a face-to-face, and subsequently calls an old associate (Mehdi Nebbou‘s famed Parisian television reporter Axel) to add much-needed clout to the investigation while also cementing himself as the lead go-between. While Carmen and their employer is fine with the decision because it still gives them a byline, this change in agreement causes myriad problems on the side of those protecting Anca. The place holding her agreed to a woman and now three men (two from the country that prostituted her) are knocking on the door. And while initially a faceless subject, she’s instantly humanized once Radu meets her and understands the damage that’s been done.

Written by Claudia and Adrian Silisteanu from an actual case study, this idea of Radu coming to grips with his failings as an empathetic soul beyond making a name for himself is mirrored in his home life as well. The film is bookended with scenes at a town pool: him behind glass with a stopwatch in hand and Matei in the water trying his best to improve his speed. We don’t think anything of the opening at first because there’s no reason to do so. It’s a dinner conversation with only the two of them at the table that begins to peel underneath the innocuousness of the activity and discover how intensely Radu is instilling his own work ethic onto the boy. Doing so starts alienating his respect.

This is how he operates, though. He’s forceful and fully aware that he achieves results, but does so somewhat without tact. Whereas a more compassionate person could ease his target into a place of security, Radu finds himself berating, poking, and prodding until he/she is beaten into submission. Matei may be his introduction to failure on this front, the boy’s disinterest in the fact that his mother’s boyfriend has already improved his lap speed making it so resentment sets in when Radu’s next plan all but takes the fun out of the sport. He can’t understand the resistance — this is the path to success. He can’t see the pressure and undo stress he’s cultivating by constantly telling the boy his personal feelings aren’t good enough. He can’t relent.

Faced with similar circumstances opposite Anca, he ignores her by looking solely at the finish line. He laughs with Axel about the danger the job provides in the form of her pimp’s cronies watching with intimidation because after the interview finishes he can simply go back home. Radu believes in his heart that Anca is prepared to go on record with the press and name names concerning those who took her and forced her onto the streets. Why wouldn’t she? She’s protected and would be helping to make sure the next unsuspecting teen has the potential of being saved from her experiences. But he doesn’t understand the Stockholm syndrome that’s taken hold. He doesn’t realize that his strong-arm tactics may be identical to the ones her oppressor used.

This is the a-ha revelation — the reason the film throws chaos onto Radu’s path only to let him deflect it away. He’s in his element as the man on the ground, pounding pavement and greasing palms. But at what cost does that access come? His Parisian friend and cameraman (Nicolas Wanczycki‘s Serge) are merely following behind, moving at his command. They feel nothing because they’re outsiders hoping to attract viewers and advertising dollars by staging sympathetic interviews with family members of the victim and neighborhood kids playing soccer in the streets that facilitate this goal. They’re here because Radu begged them to jump on this story. But even if he puts his foot down by acknowledging the delicacy of the matter, it’s no longer his decision to stop.

The Fixer is about complicity, morality, and knowing when enough’s enough. It’s about looking at a given situation from all angles rather than just your own. As a journalist you must protect your source, as a father your child. Radu is learning both these things with every misstep supplying consequences beyond his means to rectify. Istodor brings the character to life with tenacity and excitement in the chase. He oozes the confidence necessary to let a dead-end roll off his back and find an alternative solution. The way he tries to charm those who refuse to see eye-to-eye (whether it be a wizened nun or an eight-year old boy) simultaneously impresses and mortifies you. He isn’t ready to escape his flawed identity and it may just destroy him.

The Fixer is currently playing at the Toronto International Film Festival.