It’s East Berlin, 1984—an entire nation under the Stasi’s watchful eye. Freedom is near impossible without risk of arrest or bullet courtesy of a botched escape west, the life of a sailor a young man’s one legitimate avenue out. With destination an afterthought, the open sea becomes every lucky appointee’s gateway to the world and a future. But like all oppressive regimes, false hope keeps the unhappy rabble in line. If workers strive to please, the promise of reward succeeds despite its empty, manipulative lie. Unable to risk defection via a one-way ticket to anywhere, the Germans only send those with family to leave behind as collateral. Those without must remain trapped in their cage on the docks, receiving instead ‘an opportunity’ to turn snitch and gain the responsibility and power necessary to transform into the very thing they hate.

Director Toke Constantin Hebbeln and co-writer Ronny Schalk expertly infuse their film Wir wollten aufs Meer [Shores of Hope] with the lack of independence and autonomy inherent to this era of German history. Whenever a character believes he has stolen an advantage, the hard truth of this thought’s journey being carefully calculated and controlled by the enemy is revealed in stunning fashion. We in the audience become as deflated as those left to languish in prison—literal or figurative—onscreen because our desire for vindication and a happily ever after is too strong to combat the bleak reality of a socialistic regime. The lengths the East Germans go in their manipulations of assets to unearth secrets big and small becomes almost admirable when the unfathomable crippling fear of life in such an establishment is forgotten.

And we’re given a front row seat to the action through best friends Conny (Alexander Fehling) and Andi (August Diehl), two optimistic young men with dreams of setting sail for greener pastures. Biding their time and bolstering their hopes, the wait is rough as opportunity for expedited positioning increases. So, when Andi is confronted with the chance to ascend the ranks by discovering his foreman’s escape plans, he cajoles his friend into gathering the information. Unwilling to trade his friendship with Matthias Schönherr (Ronald Zehrfeld) or moral code for the mere promise of preferential treatment, Conny’s sabotage of the mission puts them both in dire straits. The reality of their situation is laid forth, the Stasi stranglehold clenches tighter than ever before, and their actions are proved entirely futile.

A high-ranking official named Oberst Seler (Rolf Hoppe) is thus introduced to project his influence on the boys with threats of harm. Conny’s secret Vietnamese girlfriend Mai (Phuong Thao Vu)—a union frowned upon socially in Germany—is made vulnerable and the two must flee if they are to stay together while Andi is left behind gravely injured and in the hands of Seler’s men. Our two leads then make their way onto disparate paths: one to share prison cell 22 with the captured Schönherr and the other a surveillance position under the government’s thumb. Both attempt to free themselves from their shackles, but every move towards victory ends up one more step closer to destruction. As the years go by, these inseparable friends fall prey to circumstance as their trajectories willingly move further apart.

It’s an intriguing look into both sides of the equation as we see the situation for political prisoners and those who sold out for false freedom. Whether it’s Andi’s handler/boss in Roman (Sylvester Groth) or Conny’s warden in Fromm (Thomas Lawincky), there is always someone ahead of them on the food chain they may think can be corrupted into helping their cause. But the detailed web of deceit at play is insane as characters come and go with differing motivations only to end up double agents or worse for missions that appear on the surface to not warrant the trouble. Every second of these prisoners’ lives is documented and every action taken a result of the situation forced upon them. Secrets are impossible for either side as the Stasi definitely abide by the ‘keep your enemies close and your friends closer’ philosophy.

There is an authenticity to everything that occurs as the film transports us to a place hard to believe was less than thirty years ago. Whether abused physically or psychologically, both Conny and Andi are made shadows of the men they were—beaten by the system and almost unwilling to fight any longer. Fehling and Diehl are fantastic at traversing the myriad situations placed before them, projecting the perfect amount of emotion at a time where the slightest outburst could give everything away. And while everyone around them changes sides, they never forget each other or stop attempting to possess the patience necessary to one day reunite with Mai. Battered and torn, the final resting place for each says more about the amount of oppression outside the prison being larger than inside than it does their level of resolve.

Through attempts at prison reform by bribery, earning safety with duplicitous actions, and simply staying alive when all optimism is lost, Shore of Hope shows how even the most impossible situations can be conquered if you just believe. A bittersweet tale with its fair share of tragic events blocking progress at every turn, we continue to trust Conny and Andi will one day find one another away from Germany and away from the decade lost by their miscalculated greed. In the end, it only took one tiny mistake to render all chance of independence moot. Whether these men followed through with that first mission or not, the act of meeting with the intention to do so sold their lives to the enemy. What they did with their souls was up to them.

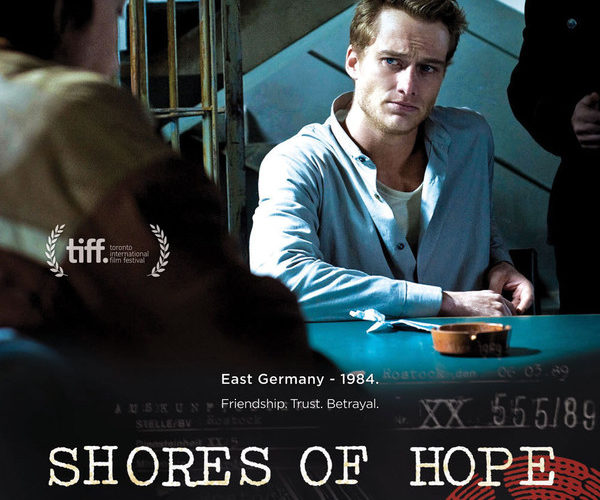

Shores of Hope is playing the Toronto International Film Festival Sept. 8th, 9th & 16th.