Writer/director Alexandra-Therese Keining‘s adaptation of Jessica Schiefuer‘s 2011 August Prize-winning (Sweden) young adult novel Pojkarna (translated as The Boys but changed to Girls Lost for international release) is deliciously dark and profoundly vital. It definitely lends itself to the genre with overt metaphors between three female classmates finding themselves budding into women as the flowers within one’s mother’s greenhouse follows suit, but it also possesses an edge that’s easily able to render cliché moot. The whole body swapping cinematic trope has been done to death in Hollywood, but never quite to this extent. Whereas previous work has skewed heavily towards the conceit’s inherent comedic possibilities with obvious lessons learned and romances kindled, Keining and Schiefuer go farther than entertainment value for resonate political commentary, authentic sexual evolution, and the universal struggle towards self-identity.

Best friends Kim (Tuva Jagell), Momo (Louise Nyvall), and Bella (Wilma Holmén) are an inseparable team born from mutual appreciation that’s almost grown into necessity to combat the regular abuse targeted towards them. Verbally and physically assaulted as though the right of every kid in the school—teachers even turn a willfully blind eye before victim-blaming the girls as “part of the problem”—each day becomes more tortuous to bear. The trio’s only reprieve is the quiet calm of Bella’s late-mother’s garden, planting new seeds so life can flourish where theirs has been stunted outside. They idly hypothesize that the ridicule would stop if they were simply “one of the guys” and it’s not a far-fetched notion on their part. Thus far unbeknownst to them, a mysterious flower’s appearance with a vanilla-flavored excretion can magically grant that wish.

With one sip of the sap the girls transition genders to live like the other half. This alternate Kim (Emrik Öhlander), Momo (Alexander Gustavsson), and Macken (Vilgot Ostwald Vesterlund) are instantly empowered with confidence to run to the school they generally avoid as a rule once the last bell rings. Their tormentor Jesper (Filip Vester) barely gives them a glance and tough guy Tony (Mandus Berg) actually approaches to recruit them into his posse for soccer and beers. A whirlwind of a waking dream, the spell eventually wears out by morning where appearances are concerned but the newfound vigor providing strength in posture, attitude, and desire remains. Their secret facilitates the power to escape lives they’re no longer comfortable leading. While it’s welcome camouflage for Momo and Bella, however, the transformation soon proves much more vital for Kim.

Where Girls Lost succeeds best is in its disinterest of happy endings or concrete answers. Rather than solve the girls’ problems, this fantastical development illuminates what the problems truly are at a fundamental level beyond merely achieving social acceptance. There’s more happening in their lives than trying to survive the turmoil of adolescence. They can’t quite verbalize what it is beyond expressions of unfamiliarity and self-hatred until finding themselves as the “other” and acknowledging how the experience infers upon whom they are inside. For Momo and Bella the transition is exciting and a reprieve from identities automatically dismissed due to bully word-of-mouth branding them outcasts, but Kim discovers something different. It’s as a boy that she looks upon a mirror with pride for the first time ever. Changing isn’t a simple adventure; it’s a drug she cannot shake.

Kim loses herself in this new persona, its mix of femininity and masculinity becoming an aphrodisiac of sorts capable of bringing down the walls surrounding her those in her periphery. She embraces the hardened nature of Tony and his petty criminal friends who drink and smoke the night away with a cultivated “fuck you” attitude to the world. Their appeal—the appeal of being one of them—quickly trumps who she was with Momo and Bella. It’s not because she doesn’t care about them anymore, she just never knew this other world had room for one more. And it makes her desirable like never before. Bullies begin respecting her self-assuredness, Momo’s feelings of friendship blossom into love, and even Tony’s steely façade hiding a rejected sensitive soul cracks. Sadly, not everyone is quite so ready to change yet.

This applies to Kim as well. The change turns her into someone she can accept, but it does so with consequences to her personal life, morality, and aggression levels. The entire story becomes set adrift into a pool of volatility as the flower’s hold on them grows exponentially with its waning health. Supply and demand sets up withdrawal, jealousy, and fear as those who should want the best for Kim selfishly try to box her in as those she hoped to open up to the freedom she’s discovered reject themselves and therefore her in the process. There will always be impediments towards happiness—internally and externally—those struggling with sexuality and gender fluidity more so as equality appears to continue being nonexistent into the next generation and beyond. Choosing a path isn’t something to be undertaken lightly.

Keining and Schiefuer take special care to put this struggle at the forefront of what could easily have devolved into sentimental drivel or farcical fluff. Their magical realism isn’t at the behest of some entity; this isn’t a parable placing its characters in the crosshairs of controversy to prevail or succumb to an outsider’s notion of righteous decency. Kim et al are in control of their actions and far from perfect. The flower simply supplies the ability to see beyond black and white—with great morphing effects and casting seamlessly transitioning the actors in real time—and let their emotional and psychological instability infer on the gray path to take. Remorse and guilt drive them to seek another way and they ultimately find more of each in the aftermath. The question becomes whether they’re better prepared to confront it.

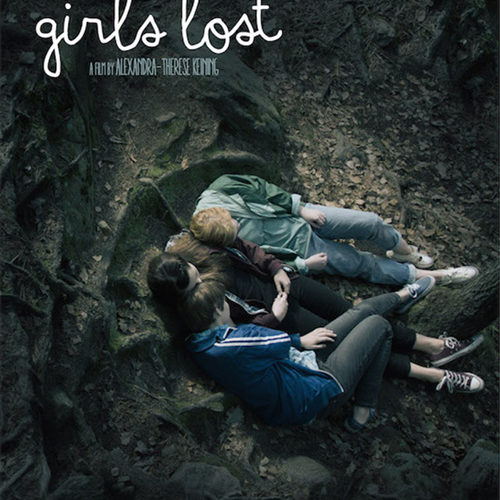

Girls Lost premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. See the trailer above our coverage below.