With the world caught in a time and place allowing it to quickly judge so much on so little, tiny human stories like Black Kite prove to be their most potent. Ask Americans about the Taliban and some will probably say the term is synonymous with ISIS, their lazy round-up of terrorist labels from the Middle East ultimately falling under the unfortunate umbrella of Islam at-large. It’s a real shame because this means that too many of us don’t know anything of the beautiful cultures countries like Iran, Iraq, or Afghanistan (where the Taliban originates) possessed and continue to possess today. They only see death, beheadings, and buzz terms like Sharia law because the media and government seek to feed us easy fear rather than educate sprawling complexities.

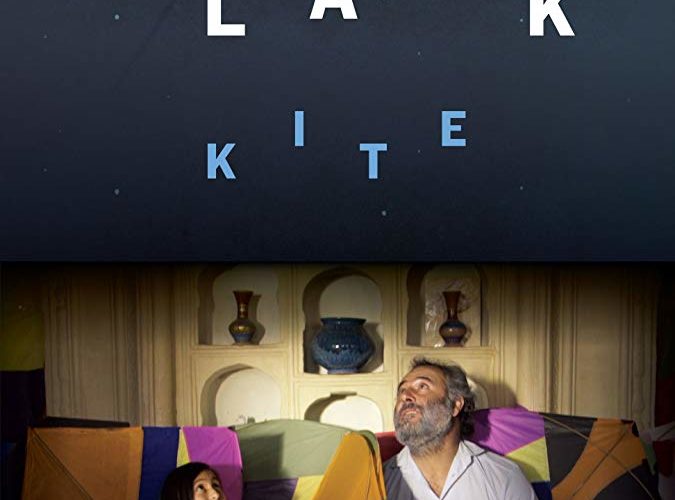

Like the title says, writer/director Tarique Qayumi’s latest is about kites — but not as you know them. While toys for children, they take on greater meaning here than even India’s Uttarayan supplies. They serve as a symbol of strength and community as hundreds war in mid-air to cut strings; a reason for parent and child to enjoy the sun; and even as a resistance movement’s color-coded message system. They’re a reminder of the vitality Afghanistan possessed, the freedom to not worry about an oppressive regime promising peace at the end of its sword. It wasn’t that long ago when the country was on the rise, opened to a modern world while still retaining its culture under a benevolent king. With every passing year, however, darkness began to fall.

Much like Persepolis did for Iran’s changing social climates, Black Kite does for Afghanistan. It follows Arian (Haji Gul Aser) from youth to adulthood via a flashback tale orated to his cellmate (Sin Mim Alavi’s Najeeb) as they await their hangings. He’s gone against the rule of the land, committing a crime so “heinous” that he’s sentenced to death in front of his young daughter (Zahra Nasim’s Seema) and the very community he never gave up on. Only when reaching the end do we know exactly what he has done, the context of which arrives from his actions as a boy and the tragedies he endured as a young man. We watch as his nation moves towards the light only to have it extinguished as quickly as it came.

And through everything are those rice paper kites calling him, diverting his attention from his studies to dream of one day operating his father’s (Hadi Delsoz) shop — learning trade secrets to become a purveyor of freedom. As a boy (played by Hamid Noorzay) he practiced on the roof any chance he got until it became too great a distraction. As a teen (played by Masoud Fanayee) he lived his dream while communism entered their land and threatened their safety, the joy of flying his creations soon usurped by the demands of an old man (Kaka Nabi) dictating his flights for reasons he couldn’t comprehend. Marriage follows (to Leena Alam’s Jameela) and not long after Seema’s born. The Mujahideen’s advancement towards Kabul continues, but hope for their family remains.

It’s a bittersweet tale of perseverance against adversity, of war without ever showing a single gunshot (although there’s a devastating one heard). We see national metamorphosis through the eyes of a simple man whose profession and greatest joy is taken away by men seeking control by any means necessary — even if it’s by warping the things they don’t like into sins against Allah. Qayumi includes archival footage of the past’s glory and nightmare, fast-forwarding Arian’s story with historical context for our sake more than Najeeb’s. And with that come animated sequences of dreams and fantasies created by Kunal Sen, lyrical passages of free kites flying without the fear their human counterparts must reconcile below as beautiful art is forever relegated to enemy of the state status.

Bookending the film with Arian’s current position on death row allows us to gradually realize how bad citizens with no Taliban affiliations have it in a state ruled by their laws. The quickest way to tear down our defenses — those that render all Afghan people terrorists — is to play into that preconception. Give us a reason to mistrust Arian by taking him away to share a cell with a murderer. Make it his duty to change our minds through words as he works to thaw Najeeb’s own prejudices. Expose the fact that this war America has fought for so long isn’t against a nation. We shouldn’t naïvely ignore the plight of people struggling to survive like us against this tyrannical force that’s literally usurped their entire history.

So while Arian isn’t your usual hero archetype, he’s a relatable character that resonates as one. His bravery may not be seen in the light of day or even be done wittingly at times, but he doesn’t apologize when caught either. He stands as a common man who accepts his fate as a martyr from the moment his country forced the choice. It’s his heart that Black Kite holds sacred, his innocence a weapon the opposition must destroy. Qayumi therefore takes us on the journey of a life worth remembering, an inspiration of hope amongst the terror suppressing it. Only when you lose something so profound as the right to experience joy can a child’s plaything transform into a symbol of rebellion. Americans would be smart to appreciate this lesson.

Black Kite premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.