There’s an interesting framing device within Felix Van Groeningen’s Beautiful Boy that strangely only frames the first half of the film. It’s a scene wherein David Sheff (Steve Carell) is conducting an interview with a Dr. Brown (Timothy Hutton). The latter assumes it’s for a story considering the former is a journalist, but this inquiry is in fact a personal issue. Sheff is worried about his son Nic (Timothée Chalamet), a crystal meth addict who’s disappeared. He wants to get a better handle on the physical destructiveness of the drug and what he can expect as far as rehab options. The answer is more scientifically technical than I expected and ends with a sad truth: recovery stats are in the single digits. What they don’t explain, however, is the percentage of that number who are white.

I don’t want to diminish what is happening in this film. I don’t want to say that Nic’s problems aren’t important or worthwhile—especially because he and his father are real people who endured the pain and suffering we see onscreen. What I cannot ignore, though, is his opportunity. I can’t simply pretend that his survival wasn’t at least partially impacted by having an affluent family, caring parents, and access to state of the art facilities let alone the chance to try his hand at a good college without worrying about finances for a healthy distraction. Nic as a character is therefore mired in his privilege despite his legitimate depression. And while I could look past it initially since the film truly starts as David’s story and how a parent copes with his guilt and futility, the narrative shifts. Frankly Nic’s journey isn’t as interesting.

I blame a script attempting to simply do way too much at once. This is because Van Groeningen and Luke Davies have decided to adapt not one, but two accounts of the story. Both David’s book Beautiful Boy and Nic’s Tweak are credited and I have to imagine that’s why we get the change in focus. Once the story leaves David’s house, we have to pick up with Nic and what happens in the aftermath with him alone. But this section isn’t very long. What seemed like a division to focus on how his mother (Amy Ryan’s Vicki) also copes with having him under her wing quickly reveals itself as a stopgap. We’re ultimately taken right back to David to reinforce his importance in the overall story and why the film feels less effective when he’s absent from our sight.

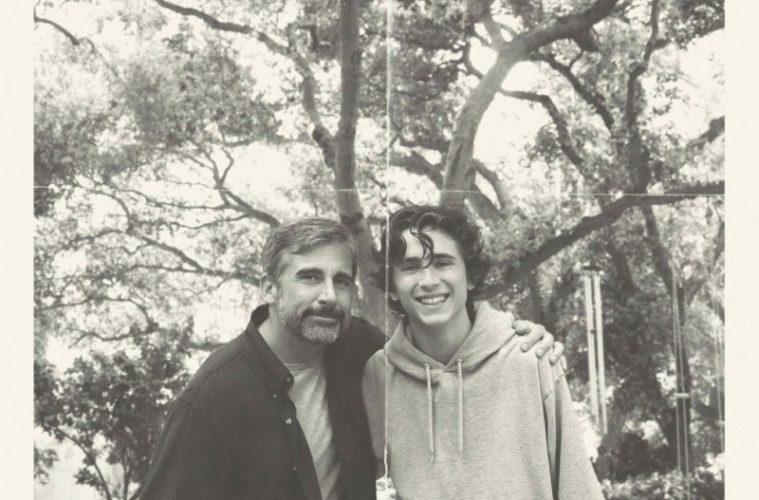

There’s some great stylistic choices in this first half from the killer soundtrack to multiple intercut sequences comparing and contrasting David and Nic’s relationship now and the not so distant past. Van Groeningen instills a resonant sense of reverie to portray the emotional distress at play. It also shows how David being stuck in the past exacerbates things, his refusal to accept his son as the man he’s become rather than what he hoped a constant reminder of his misguided blame. We really delve into his psyche—the helplessness and fear—by letting those memories take center stage alongside his worry. Nic is more or less a prop, a catalyst for this side of addiction so rarely given the spotlight to shine. Carell might be miscast thanks to his angry screaming forever linked to Michael Scott, but I thought his performance was heartbreakingly pure.

This role is complex because it pulls no punches as far as his implicitly controlling nature with Nic despite what seems subjectively to be a more caring attitude with his younger children alongside new wife Karen (Maura Tierney). She has a lot to do with this because she’s there while Vicki wasn’t. That fact—through no one’s fault—changes the parenting dynamic for the little ones and provides David a different path through their childhood than he had with Nic. He still can’t help wondering if he could have saved his eldest son by doing things differently, though. He can’t relinquish the immense guilt that drives him to search the streets in the middle of night with the hope Nic isn’t dead in the shadows. Give me that story for the duration. Give me more Karen too (Tierney is an unsung hero easy to forget). Let me care.

There have simply been too many films about the repetitive cycle of addiction for me to invest in Nic beyond his place on David’s journey. Again, though, that’s not to dismiss what the real Nic Sheff experienced or a fantastic performance from Chalamet. It’s just difficult to reconcile having to watch his numerous chances while knowing that many others in much dire straits never even get one. So I began to grow bored of Nic when front and center. I began to resent him—something that could have been avoided if not for the shifting narrative. If this was Nic’s story from the start I wouldn’t know a better avenue existed. And if it remained David’s throughout I could continue seeing the teen as the tragic cautionary tale he should be rather than the selfish plot device he becomes.

On a purely aesthetic level, however, Beautiful Boy suceeds. Those moments of reverie arrive with such optimism and the soundtrack driving everything is killer. Music seems to be a big part of David and Nic’s relationship thanks to mentions of taste in passing and automotive singalongs if not explicit evidence. It’s the type of connection able to drive home the truth that some tragedies can’t be avoided. Sometimes you can think you’re doing everything correctly only to see your kid stray towards destruction. That speaks to the guilt consuming David and why it’s important for the addict’s support system to seek help for itself. The nostalgia of the past is therefore his memory as a father while the pain of the present is his acknowledgment that things played differently for Nic. But we understand this without following the teen down his spiral. Doing so anyway therefore proves unnecessarily excessive.

Beautiful Boy screened at the Toronto International Film Festival and opens on October 12.