It opens in slow motion with teenage bodies wrestling and punching inside chaotic dust swirls, one boy (Xabiani Ponce de León’s Carlos) caught isolated in the middle of the frame. He’s not looking to hit any of the others. In fact he’s barely dodging out of the way when they come too close. It’s almost as though Carlos isn’t even there, his mind and body separated as two halves of the same conflicted whole. He knows he should be present with his friends to show his machismo and do Mexico proud like the soccer team soon to hit the 1986 World Cup pitch, but something is calling him in the distance that he can’t quite see. It’s punk metal versus new wave blues, hetero-normative conformity versus queer counter-culture.

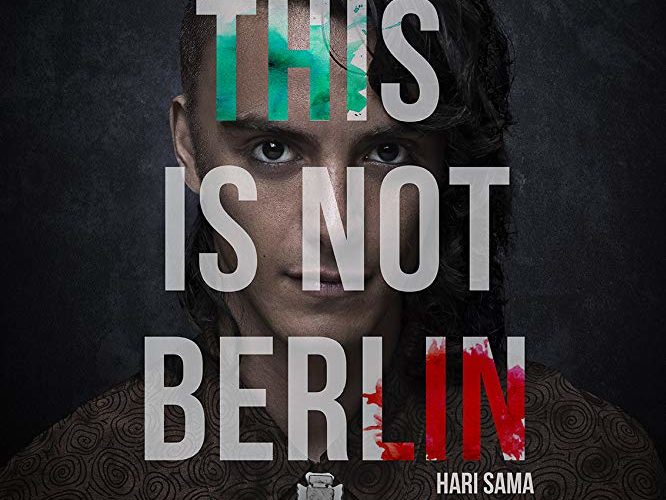

Director Hari Sama’s opening scene to This Is Not Berlin is the perfect prologue for its rebellious themes. Rather than let the boys in chokeholds be the rebels, however, it’s Carlos removed from the violence who proves the true soldier of this culture war. The fact he ends up fainting only to wind up in the backseat of his friend’s car as they drive away only cements him as an outlier dragged around more than someone trying to fit in. The latter’s imperative is a motivating factor merely as a means to remain involved in his gendered age group’s highest social circle. So when best friend Gera (José Antonio Toledano) says he’s never going to another brawl, they know it’s out of their control.

Enter the Aztec: the coolest downtown club these suburban offspring of out-of-touch middle class parents could hope to sneak into. Gera and Carlos want to go without having any clue as to what to expect. They just know that the former’s sister and latter’s crush Rita (Ximena Romo) often plays onstage with her band. One huge favor later and they’re being ushered through the door on her arm as fresh, baby-faced meat to bear witness to a synth rock orgy of sex, drugs, and political art. When asked whether their eye-opening experience has occurred at a gay bar, Rita replies, “It’s an everything bar.” And she’s not wrong. It’s a melting pot of gender fluidity and intellectual discourse these boys simply can’t receive from their sheltered upbringings.

While I know nothing about Mexico of the mid-80s, I do understand the formative qualities of walking into a new world you couldn’t have imagined on your own. And for two kids like Carlos and Gera who were already questioning their place within the prison of comfort their respective depressed (with good reason) and bored folks have provided, there’s no turning back. The setting alone becomes their addiction before they even try a drug stronger than beer. Suddenly Gera is no longer the little brother Rita yearns to leave behind and Carlos is no longer a pariah standing at the fringes. Sama and cowriters Rodrigo Ordoñez and Max Zunino focus upon the latter boy the most, his artistic sensibilities readily absorbing the enigmatic Nico’s (Mauro Sanchez) radical ambitions.

Because they’re awakened beyond internal desires, however, allows the film to be one that possesses more than a few similarities with today. It’s much like the realization made by teens two or three generations removed from boomers too self-satisfied and delusional to realize their continued refusal to get out of the way like their parents via retirement is what’s keeping our youth from finding their full potential (not laziness). By insulating their kids in “a better life,” parents have the tendency of filtering out realities they feel their success has erased. More than sexuality, these boys are being stripped of their rose-colored glasses of privilege. Who’s dying? The AIDS-afflicted contemporaries Carlos endears himself towards. Who’s “pretty?” Gera’s prejudiced ilk working tirelessly to be “better than.”

This isn’t some devolution to squalor or self-righteous soapbox reappraisal of who they are, though. That privilege is something they carry with them regardless of what new worlds allow them entrance. It’s the difficult truth that will ultimately save them when their new friends in similar positions would be left to rot in their place. There’s still that chip on Carlos and Gera’s shoulders of entitlement, a trait carrying through like it’s embedded in their DNA. It’s what allows Carlos to still fight his mother (Marina de Tavira) for what she became to give him that better life rather than acknowledge how alike she might have been at his age. It’s why Uncle Esteban (Sama) can be trusted as an equal for pushing aside conformity as a necessity.

And yet we look at Carlos’ trajectory and still see compliance. We watch him lie by omission about being attracted to Nico because it allows him a seat at the table of crazy performance art protests supplying him a personal escape as much as delivering an important message. When Gera finds himself left behind — holding onto his “pretty” status too steadfast — he reacts by going further down the rabbit hole than caution recommends. The Aztec and its inhabitants are a white-hot flame of life incarnate, a live wire that risks burning them all alive if they aren’t careful to curb their excess. What they do is necessary for their quests to unearth their true identities, but you cannot ignore the safety net they’re so quick to reject.

It’s this blindness that creates the most interesting moments since Sama refuses to simplify the complexities of adolescence at a time of rebellion (something you could argue is adolescence by definition). This whole adventure starts as a way for Carlos to get closer to Rita and yet it’s Nico, Maud (Klaudia Garcia), and Ajo (David Montalvo) — characters she knows to keep at arm’s length and implores him and Gera to follow suit — who give him the literal and figurative drugs to bring into focus that which was blurred during the opening scene. Visual and narrative connections such as this are plenty throughout This Is Not Berlin, but none seem contrived thanks to the raw performances from de León, Toledano, Romo, and Sanchez. They captivate us completely.

Their outcasts from “civilized” society are what every generation needs to wake itself from the doldrums of complacency and the oppression of a political and economical hierarchy dictated by race, gender, and sexuality. And while what occurs may seem familiar to the countless cinematic accounts of post-punk coming-of-age dramas set against neon strobes and rock music of European pedigree, this is very much about Mexican history and that nation’s participation in an international culture shift still being fought today. The events onscreen are semi-autobiographical for Sama and thus a document of the turmoil those his age at the time faced when external expectations and internal hopes clashed. At its center: love. The power it has to bring us together opposite its potential to tear us apart.

This Is Not Berlin premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and opens on August 9.

Follow our festival coverage here.