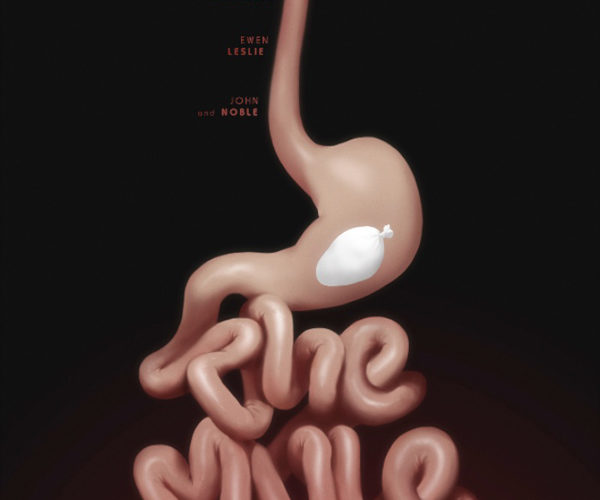

Directors Tony Mahony and Angus Sampson‘s The Mule is not at all what one might expect. The marketing materials draw it up as a B-movie romp, something the involvement of Sampson and Saw co-creator Leigh Whannell (they co-wrote this one together from a story by Jaime Browne) helps corroborate. Besides a couple gross-out moments due to the excremental nature of the plot, however, the film proves differently. It’s instead a rather slowly paced true-life thriller spanning two weeks while the authorities wait on their captive Ray Jenkins (Sampson) to relieve himself of the twenty condoms full of heroin he swallowed in Thailand. The intricacies of the yarn they’ve woven increase as new revelations about who’s involved and role reversals concerning who’s on the take are exposed to ultimately prove the journey rather engrossing as a result.

Set against the backdrop of the 1983 America’s Cup—an underdog tale of its own for which its Australian audiences can relate Ray Jenkins’ uphill adventure to—The Mule‘s simple catalyst of greed throws a sleepy town on its head. The public believes Pat Shepherd (John Noble) to be a businessman with a giving heart who puts his money back into the community when the reality soon exposes him as a criminal kingpin who uses the amateur sports team he sponsors as drug mules. Gavin (Whannell) is his right-hand man, someone who has cultivated the face-to-face relationship necessary in Bangkok and feels ready to up the ante for himself. Recruiting his unfortunate childhood Ray to bumble in and out of customs, Gavin’s delegating of resources behind Pat’s back leads to a series of unforeseen consequences.

Opening on Ray bending over and dropping his drawers at the airport, we know he’s been caught before we discover what he’s retaining. The movie rewinds a bit to meet the players, learn the dynamics between them, and watch as Gavin uses Ray’s past friendship and present financial difficulty to gain his trust and attention. Proverbial “brothers”, the word is pure manipulation for one yet oath to the other. So even though Ray is ready to stand strong and prevent a bowel movement despite his stomach gurgling and expelling gas for waiting detectives Croft (Hugo Weaving) and Paris’ (Ewen Leslie) benefit, those left empty-handed without their drugs grow restless and paranoid. It becomes a race against time for our gastrointestinal behemoth to beat a court-ordered seven-day “imprisonment” as well as the criminals looking to silence him for good.

As a result, three-quarters of the film takes place in the hotel Ray is being held. The toilet doesn’t flush, there are no fixtures on the sink or shower, and the bathroom cannot even be opened without the constable’s permission standing guard. Paris plays “good cop” trying to reinforce how he’d rather arrest the men in charge than a nice guy who made a mistake and Croft delivers “bad cop” with his aggressive nature, uncontrollable impatience, and delight in beating his ward any way possible if it might help those plastic pouches vacate his intestines. A lawyer is eventually added to the mix too (Georgina Haig‘s Jasmine), one finding her own bit of greed with the decision to care less about her client being guilty and more about beating the too quick to trample on human rights police.

So while the subject matter is rather dark and disgusting, the tapestry of players expanding wider and wider shows Sampson and Whannell’s intentions are more about the duplicitous nature of mankind than whether or not Ray remains constipated long enough to avoid jail. It has some funny parts and characters—Ziggy the Lithuanian (Ilya Altman) is one of my favorites—but it’s first and foremost a period-based crime drama using its twists and turns for quality suspense rather than laughs. A tone of severity looms above the whole as Ray writhes around in his bed desperately trying to keep calm so no one gets in trouble. As the days carry on, however, it becomes clear the exponentially dire situation has grown to where our naïve mule must figure out it’s his own back that needs watching.

Everyone involved excels at keeping things rooted in reality while leaving the door open just enough for laughs to appear naturally. The Mule may be inspired by true events, but as the end credits’ disclaimer explains much of what the filmmakers include—names, timelines, etc.—was changed. Those inhabiting the drama might be stereotypical stock characters, but they each have enough depth to prevent their actions from being forgettable. Weaving relishes the opportunity to engage in smarmy fun; Whannell gives the best performance I’ve seen from the writer yet; and Sampson is a perfectly schlubby everyman we can get behind and applaud for his steadfast loyalty to those he loves. His Ray goes above and beyond the call of duty to ensure we’re treated with an entertaining mystery rather than the throwaway comedy I assumed.

The Mule opens in limited release Friday, November 21st.