I had never heard of Donald Crowhurst before seeing James Marsh’s film The Mercy. This is unsurprising since the British Sunday Times‘ Golden Globe Race of which he was a competitor occurred in 1968, not quite fifteen years before my birth. And if his would-be return-date to Teignmouth, England of July 1969 after yachting around the world without stop or assistance was ingrained in my mind for any event — auspicious or infamous — it was the moon landing. So when the synopsis described this amateur sailor as a man who sought to fabricate said journey despite never leaving the Atlantic Ocean due to seven months of disastrous circumstances, I obviously believed him to be a charlatan. As written by Scott Z. Burns, however, the truth proves much more complex.

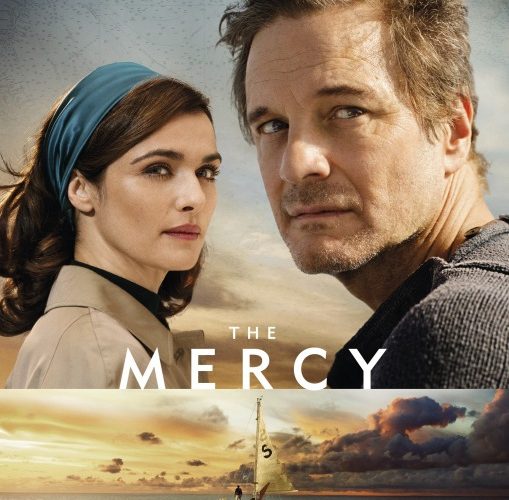

Crowhurst (Colin Firth) was like many of us: an ambitious working class citizen with a good life who yearned for more. He was an inventor of nautical instruments, a loving husband, and father of three. To therefore hear Sir Francis Chichester (Simon McBurney) talk about his own adventures traveling the oceans by boat before announcing the aforementioned race was to see a way towards financial security and celebrity acclaim. If Donald could bring his ideas and technological advancements to fruition with local entrepreneur Stanley Best’s (Ken Stott) money, he could theoretically win that race. He more or less bet on his mind to manufacture the perfect vessel that any layman could use to accomplish the unthinkable. And if he did somehow win, his products would figuratively sell themselves.

The film documents his lofty goals and inevitable stumbles. As his departure is delayed and his ship forever dealing with unforeseen issues, no one would have blamed him for saying enough was enough. His wife Clare (Rachel Weisz) never thought this enterprise would go farther than having a new boat to show for the effort, but she didn’t know the deal Donald made to push forward. She was in the dark as to how deep into the hole he went leveraging the present and future to pray for a dream his publicist Rodney Hallworth (David Thewlis) had sold to the community at-large. Eventually it becomes a choice between destitution and the slimmest chance of avoiding destitution. He picked the latter, compromising the very ideals he hoped to strengthen.

So we watch his struggles in the middle of the Atlantic, his dreams falling apart in his hands. The assumption is that the video, audio, and written documents the BBC asked him to record corroborate the tenacity Crowhurst reveals onscreen. From bailing out his engine, fixing holes in the hull, and waking to discover his sail taking him back to where he started, Donald is put through the wringer. It’s depicted by a physical disintegration with Firth growing gaunt and dejected as well as an emotional one with his phone calls to family and partners (as Best and Hallworth become) portraying a lessening of spirits. He acknowledges his failure and works feverishly to conceal it with a plan consisting of too many moving parts out of his control.

What makes The Mercy interesting above its central performance (Firth delivers a heartfelt turn as a man looking back at what he had before realizing too late that it was enough) is the back and forth from yacht to mainland. While Crowhurst schemes his way towards literal survival, Hallworth does his best to make him a star before he’s done. This is a former crime reporter turned agent who isn’t averse to bending the truth for extra drama himself, building up a hero from what ultimately become the ravings of a madman gone too long from normal life. At one point his embellishments actually force Crowhurst to augment his own, their lies compounding until radio silence becomes the only real way to stop things from advancing beyond possibility.

There’s an impression of authenticity to the way this additional manipulation is almost dismissed as acceptable whereas what Crowhurst spins isn’t. This second layer of deception unfolds with a scary sense of status quo as Hallworth pats himself on the back whenever the Sunday Times documents his client in the big city and forces Clare into the spotlight as the sole emotional connection to the man on every Englander’s mind. He creates an intrusive circus at her doorstep to show how the feel-good stories often find themselves buried under more collateral damage than tragedies if only because they often transform into the latter for an extra chapter more provocative than the first. I only wish Burns and Marsh delved deeper into the significance of this pervasive act.

They hardly ignore it considering the time spent with a delighted Thewlis always ready to celebrate a competitor’s demise. Weisz even gets a memorable bit of dialogue in which her Clare excoriates the media for its role in pushing her husband to the edge of sanity in pursuit of a nation’s collective aspiration. Perhaps my gripe with the film turning the spotlight onto this issue at the eleventh hour is more a comment on our ability to ignore media sensationalism than a fault of the script. I guess it was always right there at the forefront, thus making myself the one to blame for believing it background dressing. Maybe The Mercy‘s greatest strength is that pragmatism to fuel its eleventh-hour chastisement of anyone blind to Hallworth’s complicity.

That also doesn’t mean liberties weren’t taken to render it this way and allow Crowhurst the empathy Marsh and company would like us to give him. In the end this is a sympathetic portrait of a man who painted himself into the corner that will ultimately become his prison. It portrays the very human impulses that set him on a course of following unwise ambitions with fear masked as hubris. To see Firth’s face when he begins his journey is to see a man who isn’t sure he’ll ever return. All the brazen declarations at the start are erased with each setback, his only hope to avoid ruin being a wing and a prayer. So we need Hallworth as a quasi-villain to let Crowhurst earn our remorse.

The Mercy opens NYC on November 30 before receiving a one-night nationwide event showing on December 6.