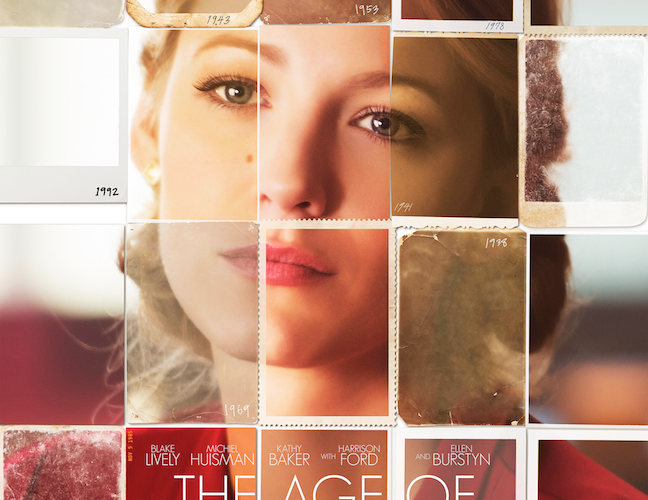

If Nicholas Sparks took a stroll through The Twilight Zone, it might look a little like The Age of Adaline, a new fantasy ambitious enough to make the case that looking like a 29 year-old Blake Lively for over a century is actually a curse. To director Lee Toland Krieger’s credit, the film does develop an effective note of melancholy and wistfulness; Lively, too, hits the right notes as a woman who has lived so long that everything passes by without as much fuss, fret or passion as it once did. For the cynical, this may become a slog, but Adaline turns out to be so earnest and genuinely sweet, that one should be able to forgive its schmaltzy excesses, especially when one of them is Harrison Ford’s best performance in years.

Time now stands still for Lively’s Adaline, who lives as a reclusive librarian who looks 29 but is actually 107 years old. In a creaky and overly talky voice-over we learn that Adaline, shortly after losing her husband, was in a terrible car accident that resulted in a strange confluence of elements–an icy river and a current of electricity—that allowed her to walk away as an eternal twenty-something. Although a film like Adaline would seemingly traffic in magical realist touches, the narrator feels the need to point out that the freak accident that revived Adaline is not magic, but science (just science that won’t be discovered until several years in the future). This conceit isn’t particularly explored beyond the initial presentation; it mostly allows us to have the ageless nature of a vampire movie without the bloodsucking.

In fact, there’s a thematic kinship between this film and Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive, that presents Adaline as a character who has grown weary and somewhat disconnected—for Adaline more than the vampires, it’s the distance she faces with those that she loves but knows she will lose—but soldiers on, because, really, what else is there but life? We learn she’s still mortal but won’t die of natural old age, and has lived to the point that she embraces her elderly daughter (Ellen Burstyn) while remembering a time when she was a very young child. Romantic entanglements have never much worked for Adaline in the long-run, because for her, the run is much longer than any of her paramours. Of course, this is still a metaphysical romance, and what would that be with a heroine that has eternally sworn off men? So, Adaline meets Ellis Jones (Michiel Huisman), a winsome historical preservationist (he’ll find few things as historically well preserved as Lively) who wants to spend his life with her but finds she’s a bit resistant. Their love affair is pretty but rather vague and sort of bland, which characterizes a good bit of Adaline up to this point.

The film’s technical credits all look great, and the crew go to some length to make Adaline look breathtaking in every era it represents. Lively does a nice but somewhat stilted job as the titular Adaline, and she looks supremely lovely but doesn’t always register as the kind of versatile, experienced being that one such as she would have certainly become over the long years. Huisman is fine, although Lively’s relationship with Burstyn is more dramatic and poignant. There’s a feeling that Adaline is aiming at an out-of-date subgenre that peaked with the likes of City of Angels, Meet Joe Black or What Dreams May Come. Then, it gets to the moment where Huisman introduces Lively to his parents, played by Harrison Ford and Kathy Baker, and the film transforms into something entirely more interesting. The not-so-hidden twist is that Ford’s character, William, was Adaline’s lover from the past and although Lively lies about her real identity—Ellis knows her as Jenny and she claims Adaline is her mother—there’s no fooling Mr. Jones. Baker comments about the way that her husband stares at their son’s new-found love, and Ford’s eyes do indeed convey a great ocean of love, loss and hope.

He may have the same last name as Indiana, but William has much more in common with less-surly and more subtle characters in the Ford ouvre, most particularly his detective from 1985’s Witness. Like that film, you can see Ford unpacking a great variety of emotional sensitivities from a suitcase of guarded, cautious external behaviors. His work with Lively is the only time the actress really comes out of that immaculate shell the movie’s premise has developed for her. There’s no real love triangle here, but rather just contextual human references for the way Adaline’s life ebbs and flows, gifting and taking away as it goes. The way Adaline and William deal with their reacquaintance hints at a much stronger, braver movie that this Age only partially becomes.

Age of Adaline ultimately relents from its more intriguing notions in the second half, and goes for the more audience-friendly conclusion that opens up even more practical questions. There’s also a not-surprising urge to ignore the creepier implications of Ellis finding that the woman he’s with now is really dad’s one great love from the past. For all of that, the movie is enticing because of how it does commit to what’s there, and how everyone involved seems to actually care about the material even when the film is merely coasting. It’s worth seeing for the visuals and for Ford, who hasn’t been this alive in many years. I have to wonder though, what might have been had Adaline tried for something stranger, perhaps confining its actions to one mind-bending dinner party like last year’s Coherence. As of now, it settles for being the most discombobulating ‘meet the parents’ since Kevin McCarthy came calling for Estelle Winwood in that Twilight Zone episode “Long Live Walter Jameson.”

The Age of Adaline is now playing in wide release.