The cinematic representation of a kind of meta-art, a self-reckoning through artistic expression, is nothing new. Whatever the form, most depictions have centered on either the creative process and its attendant difficulties, or the revelations of character that stem from the material (and in many cases both). Spettacolo, a documentary centering around the annual play staged in the Italian town of Monticchiello, largely eschews these staid subjects in favor of a more sedate, quietly ruminative view of how art and tradition are so often intertwined, and how the rapidly changing modern world affects these two cultural artifacts. Though the tone and treatment fall too often into the elegiac, there are still some surprises and insights to be found.

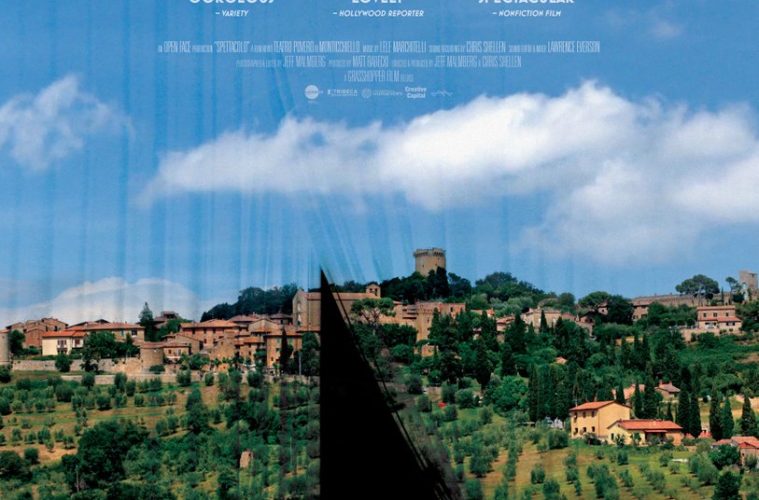

Spettacolo is the Italian word for performance or play, and for all intents and purposes this is the main focus of the film. Monticchiello, a small town with a population of, at the start of filming, 136 people in Tuscany, Italy, began mounting an annual play during the summer of 1967. At first, the content of these plays were standard historical works, focusing on ancient tales and stories, but after a few years the decision was made to utilize actual, concrete historical events from the town’s history, past and present, as the bedrock material for the play, in a concept that is referred to by the townsfolk as autodrama.

Over the years, the exact way in which this manifests itself has shifted and varied, but what remains and what is emphasized throughout Spettacolo is the sense of community in the small town. Most of the key collaborators in the play have remained since the inception of the tradition, even as they grow old and others pass on, and there is a wealth of history that feels baked into many interactions, containing intimate knowledge of each person. Noticeably, the cast and crew is comprised almost solely of the town’s elders; a frequent refrain throughout the film is the worry that young people are not interested in the play, and as such the tradition will eventually die out.

This is just one of many crises, both local and international, that dominate the documentary. The impetus for the play depicted in Spettacolo, which appears to follow the town in the year 2012, is the economic crisis, especially the imbalance between the rich banks and the poor town. Pointedly, the whole venture is called the Teatro Povero di Monticchiello, or the Poor Theater of Monticchiello, and it is made clear throughout the film that much of the intention of the play is to tackle the present moment, which is only accentuated when the theater’s primary sponsor, the Monte dei Paschi bank, is found to have been as guilty and fraudulent as the other American and European banks during preparation for the play.

But, for better and worse, Spettacolo never comes off as anything more than a portrayal of a collective, of a group dedicated to preserving their history through unconventional measures. It is clear there are many obstacles that persist, but a spirit of cooperation inevitably prevails and the play goes on. Though Andrea, the director and writer of the play each year, is perhaps the most dominant presence, he is but one of many, and directors Jeff Malmberg and Chris Shellen thankfully provide no chyrons to distinguish each person or delineate their role within the town and the production — it is up to the townspeople to divulge that information, and their words carry more weight because of that responsibility.

If Spettacolo has a significant flaw, it is in the somewhat pedestrian and placid manner in which it is constructed. There is the feeling that the directors see the play as a vehicle in order to explore the town as a whole, which does allow for some lovely moments of contemplation but makes the film less focused and motivated as a whole. The shooting style reflects this feeling: despite some nice moments of figures in contemplation, the modus operandi is one of stability, of a hands-off and observational approach. However, this is less significant in the long run, and what sticks in the mind most is the neurosis-free approach to art conveyed in Spettacolo. The problems that arise are purely pragmatic: people arriving late or not showing up to rehearsals, dwindling financial backing, stages that threaten to fall apart at a moment’s notice. In this climate, all that the creative personnel can do is to keep going, and they do so with admirable resolution, simply but vividly.

Spettacolo is now in limited release.