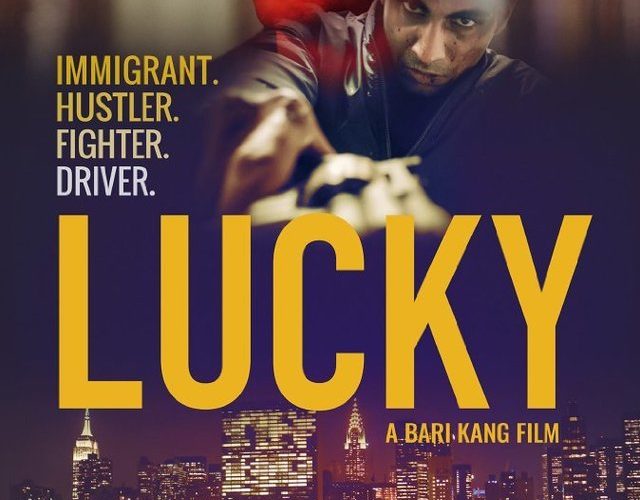

It’s taken five years for Lucky (Bari Kang) to save the money and find the footing — no matter how much illegal activity both pursuits warranted — necessary to acquire a bride believable enough to fool INS and earn his green card. He has a legit job as a mechanic with his “brother” Ricky’s (Daniel Jordano) garage during the day, helps “lose” customers’ taxis at night to earn extra cash from a fence while they receive insurance checks, and even procured himself a license from the shady jack-of-all-trades Sunny (Obaid Kadwani) to look the part of a legitimate immigrant before the law renders it official. Finally the time has arrived to take that next step forward just as fate enters to show this kind-hearted soul the irony of his name.

Kang as writer/director foreshadows this quickly spiraling destruction of his character’s dream by starting his debut feature Lucky with a scene of violent aftermath. There he is breathing heavily with a blood-splattered face, the battle that was just won physically more than likely also simultaneously lost morally. Without context, however, we merely see a man at the end of his rope, obviously forced to finish something he never wanted to begin in the first place. This is intentional because it exposes the reality of how far the optimistic man we’re about to meet weeks earlier will go for family, friends, and his own survival. It prepares us for his steep descent into the dark areas of New York City’s criminal underworld. Lucky’s only way out becomes straight through.

The steps down come rapidly, but not without authenticity. Ricky is in the hole with debtors and just disappeared with Lucky’s green card savings. So the latter is forced to go looking, using everything and everyone at his disposal — including shifty PI-type associate Mike (Ed Newman) with sources above and below the law. The hunt leads Lucky to a club with not so good clientele in one of his shop’s taxis because he has no other way to roam the city. In pops a stranger (Alfredo Diaz‘s Fernando) with enough money to distract him from his goal and suddenly he’s chauffeuring a known drug dealer who’s set upon his own mission to shore up new territory. Broke, lost, and in desperate need for help, Lucky joins the payroll.

From here the many plot threads are gradually revealed since it’s not long before trustworthy and loyal Lucky earns extra responsibility and therefore broader glimpses behind the curtained façade of “I’m just the driver.” We meet the wife and child Ricky’s gambling problem has left in the lurch, uncertain if he’ll ever return. There’s Lucky’s aunt Prisca (Pooya Mohseni), a brothel madam looking out for her nephew while working her girls to the brink of safety (Galla Borowski‘s Lola one he has a particular attachment towards). And of course Fernando’s favorite prostitute Tatiana (Natalia Zvereva), herself a single mother trying to make ends meet. Lucky becomes the one honest man on all these women’s paths and he lives up to that role without fail to his own detriment.

The film becomes his journey to salvation and redemption from a snap, greedy decision that unwittingly pulled these women into an orbit where a bullet between the eyes seems the only way out. At first it was for money — just enough to do what he needed for himself and Ricky. Then the money stopped proving enough to simply sit back and watch Fernando do what he does. But like every tale of drug-fueled unpredictability, stepping away is both impossible and a good way to widen your oppressor’s gaze onto those you love for leverage. The question becomes whether Lucky possesses the type of rage to permanently end things. Fernando’s actions inch him closer and closer to that edge as anonymous bodies begin having faces Lucky knows too well.

Kang is working on a shoestring budget, but it only shows in the sometimes-stilted performances. That’s honestly the easiest shortcoming to overlook in a film if the story and production value are good enough to sustain us otherwise. I found many similarities in tone and themes with another indie drama of the same ilk from a couple years back in this respect: Zak Forsman’s Down and Dangerous. Both have a polished score augmenting the atmosphere rather than manipulating while the use of neon reflections and nighttime cityscapes provide a great sense of place and aesthetic. But the main draw for both is a script bolstered by a complex and relatable antihero. If we’re asked to care about someone doing bad things, his motivations better be pure.

Lucky’s are despite his comfort level with victimless crime (save insurance companies no one likes anyway). We can even look past his complicity in NYC’s drug problem because he’s hit a wall and is desperate to stay afloat for others beyond himself. The plot plays up his “father figure” aspirations too high at times, but the point is relevant. And to Kang’s credit, not every woman in Lucky’s life needs him to save her. He may believe it’s so and circumstances may prove it so in certain cases, but Kang isn’t afraid to let consequences play out in order for Lucky to both fail and get duped too. He isn’t the only complex character involved and he isn’t responsible for everyone else’s actions regardless of the guilt felt.

This fact allows Lucky to overcome its familiar tropes and trajectory. We can guess how everything will turn out, but we also genuinely care about what he will be once it’s over. There’s as much opportunity for Lucky to become as broken as Ricky as there is for him to prove he’s the compassionate and strong member of society the United States needs. His path towards that end comes with a lot more forks than he initially hoped, but he has people he loves to guide his heart through the tough times that test his soul. Lucky isn’t perfect as a person or a film, but there’s something fitting about this. Escape from his character’s situation won’t ever be clean and Kang ensures to never pretend it will.

Lucky is now in limited release.