Ira Sachs‘s Keep the Lights On is a film of deep, soothing humanity, exploring the truths and fictions of a long-term relationship with prodigious delicacy and humility. That it’s based quite heavily on Sachs’s own maddening, decade-spanning relationship with Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man memoirist Bill Clegg comes as little surprise — from the first-beat credits (comprised of the delicate paintings of Sachs‘s current spouse, Boris Torres) onward, the movie is characterized by the kind of intense intimacy that, more often than not, can only arise from the most personal depths of an artist’s existential well.

Cushioned into narrative movement by a gem-level, Arthur Russell-centered soundtrack, Sachs‘s story, co-written with Mauricio Zacharias, begins in the late-1990s. Erik (Danish actor Thure Lindhardt), a talented documentary filmmaker, has seen his promising 20s pass him by, and, as his sister (Paprika Steen) points out bluntly, he has very little to show for it. Living off his family’s money, Erik has had ample opportunity to commit himself to his art, but the things he’s made have carved a negligible commercial path. His new project, focusing on the art and character of Avery Willard, is seen throughout Keep the Lights On at various stages of development, and it may be Erik’s last shot at spending the rest of his life working in his field of choice.

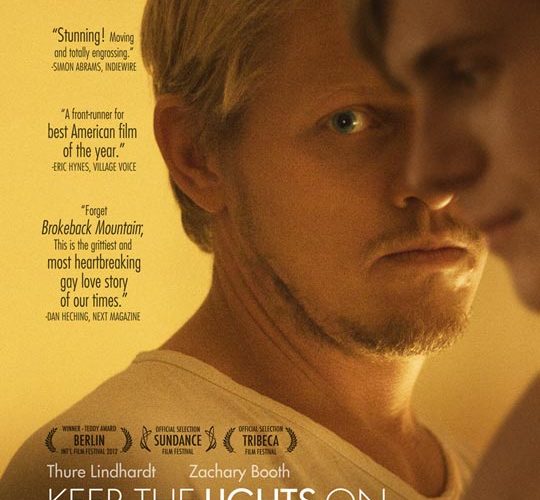

To make matters even more pressure-filled, Erik’s career concerns become completely trampled by his personal ones when a one-night stand with Paul (Zachary Booth), a publishing-industry lawyer, blossoms speedily into a passionate, full-blown relationship. As is obvious from their first encounter, which was arranged abruptly via a looking-for-sex hotline, Erik and Paul have a fanatically satisfying physical attraction to each other. The emotional chords connecting them, meanwhile, are no less potent, but they’re made very complicated by the contrasting psychological make-ups of both individuals. (The most glaring difference between the two: Paul’s crack habit.)

There are a variety of routes Sachs could’ve taken from this set-up — study of addiction, study of artistic insecurity, study of gay life in New York City across a ten-year period — and he chose the most difficult option of trying to capture every single one of them. And he pulls it off, not by implanting interactions like a script doctor or making jump-the-gun transitions, but simply by drawing these characters in great detail and then letting their inner turmoil guide the way. There are moments when the film, after carrying out yet another relationship-pondering beat, may feel like it’s treading water, but a closer look reveals a character-focused intricacy to the soft, unhurried pacing. We’re aligned with Erik from the beginning, so it’s only natural that, when he’s in a state of frustrating stasis, so are we.

Sachs is also wise — and, considering the material’s autobiographical roots, very brave — in his willingness to surrender to his actors. He gives them ample breathing room to fill in the screenplay’s white space, so that the junctures of inactivity are complemented by nail-biting behavioral depictions. Booth, with his silky voice and soft-as-a-pillow face, provides riveting implications to his simmering dark side, while Lindhardt, whose character is the film’s true lead, supplements his role with a childlike openness that takes on exalted meaning. Every time Paul goes missing, Lindhardt peels back another layer of Erik’s vulnerable skin, and the cumulative effect is magnificently human.

Because the two men are devoted to different things — Erik to the other man and Paul to his inner-demon impulses — the romance has an ill-fated air going for it early on. When Erik first sees his new lover light up, he’s tempted to dismiss it as a casual method of post-work stress-release, but there’s a visible shock in his eyes, and we can tell, in that moment, that he’s dedicated to seeing this relationship through, even though he knows it has the potential of ending in failed rehab stints and life-scarring wounds. That’s a dark realization, and it says something about the self-doubt of Erik’s character — at the beginning of the film, at least — that he’s willing to invite such a somber presence into his life.

Had Sachs made Keep the Lights On earlier in his career, the film may have been more one-sided in its hopelessness (and, in turn, likely would’ve have a different title). But it’s clear from the feathery, blinding-light palette of cinematographer Thimios Bakatakis (formerly of the highly unsettling Dogtooth) that Sachs, in looking back on this stretch of his life, has found an accessible positivity in it. It’s possible, even, that his locating of this uplifting fiber wasn’t even by choice, since Erik, when he hits rock bottom, shows signs of self-induced violence. Without that optimism, without the slight bounce you get in your step while walking through Manhattan on a breezy morning, Erik (and Sachs) may never have been able to turn the corner.

Keep the Lights On is currently in limited release.