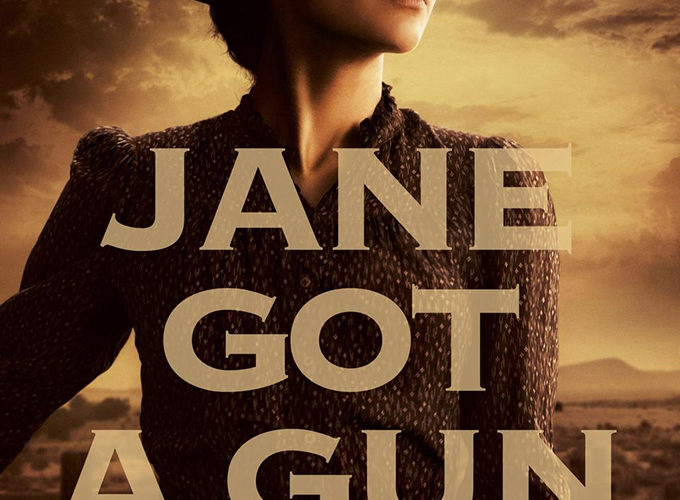

It’s a wonder that Jane Got a Gun is even out in theaters right now. Anyone with even a passing familiarity with its production headlines will have read about its hellacious development cycle – whether it be the multiple delays, or the revolving door of talent like previous director Lynne Ramsay, and departed headliners like Michael Fassbender, Jude Law, and Bradley Cooper.

Gavin O’Connor, who’s built a sturdy reputation through elevated genre hits like Miracle and Warrior, was given the unenviable job to pick up the pieces. And while he’s created a fleet, nasty western that feels uncompromising in its violence, it’s also just as quick to jettison any of the themes that have the possibility to weigh down the story. In the last third, O’Connor isn’t so much tying up loose ends, as forcing the groundwork for the tidiest ending possible.

Set in the nineteenth century in the New Mexico territory, Jane Got a Gun begins as Jane Hammond (Natalie Portman) sees her husband (Noah Emmerich) slumped over and bleeding out coming over the horizon on his horse. Bill Hammond’s finally met retribution from an infamous group of outlaws known as the Bishop Gang. Led by Colin McCann (Ewan McGregor, buried in a nearly unrecognizable bushy mustache and speaking with a mannered venom), a notorious black hat who’s been wronged by Jane and her husband, the Bishops Gang is on the way to finish the job.

Over a series of quick fade to black takes, O’Connor immediately demonstrates his willingness to show unflinching violence as Portman tends to Bill’s gushing wounds with a match and pliers. Bedridden and paralyzed, Jane sets off to find her ex-fiancee, Dan Frost, (Joel Edgerton), a former Confederate war hero and gunslinger who reluctantly helps for the right price, even as he resents Jane and her husband for how things panned out.

This is all narrative runaround to a big showdown, and Jane Got a Gun is happy to lean into the framework of the classic western as Jane and Dan get cozy and prepare to defend the family home, loading absurd amounts of weapons, and building makeshift explosives for a last hurrah.

Jane isn’t the usual damsel, and the movie’s fully aware of the genre’s expectations for women. One of the best visual gags comes in an initially cliche scene of Jane struggling to shoot a distant glass bottle with a revolver, only to pick up an adjacent rifle, and shatter it in one shot. Then again, she’s also kind of a cypher by the end despite Portman’s empathetic, yearning performance.

Edgerton’s character, on the other hand, is a familiar western archetype with his union of wounded sentimentality and gruff authority, but he has a face born for the genre with his kind eyes and rigid facial structure. And he brings a believable, mounting emotionality as the flashbacks illuminate the circumstances of how these characters ended up here.

Much of the movie is dominated by these flashbacks that take place five and seven years earlier in the halcyon days of Jane’s relationship with Dan, and before Jane became wedged between a rock and a hard place with McCann and his gang.

McGregor doesn’t often have the opportunity to play the Black Hat role, but he jumps into the character with relish as he alternates between mannered charisma and slimy amorality in the course of single scenes. His moments of menace are spare, but they’re presented with the utmost confidence, such as the juxtaposition of his gritted smirk and a tilted chair as a visual signifier of life and death for a hapless victim in an interrogation scene.

And while some of its parts occasionally feel like hand-me-downs, Jane Got a Gun has a distinctive style. Lensed by Mandy Walker, the frontier is imbued with a dusty coating, and the characters are moodily draped in a sepia glow, with much of the action taking place at night. It’s the rare western that actually takes advantage of the dark for storytelling reasons rather than as a way to obscure poor editing or filmmaking. The final set piece, especially, is a briskly shot showcase of the power of darkness and a malleable environment in a gunfight.

But in paring down the story to a tale of vengeance, there’s all these incomplete elements. One of the strangest writerly conveniences comes with the detail that Jane’s daughter just happens to be staying at a friend’s house for the entirety of the movie. It’s not just hanging plot threads, but the lack of an emergent philosophy to these characters. It would be perfectly fine if the movie wanted to hew to binaries of good and evil, but there’s a larger discussion within the dialogue about romance as a insidious method of possession.

One of the most individually interesting filmmaking moments comes when the camera stays close to Jane while she’s eavesdropping on a conversation of a group of men as they discuss what to do with her like she’s chattel. It’s a telling moment, and one that brings in a welcome pettiness to the interactions, but it’s mostly a way of foreshadowing a nicely shot but emotionally hollow gun battle.

O’Connor has a talent here for threading the needle between stylish action set pieces while also communicating their lack of grace. For instance, as bad guys explode in flames late in the movie, it’s accompanied by screaming, reminding the viewer of the viciousness of the situation. It’s maybe a little disappointing then that the movie seems to reward the violence even as the script foreshadows over and over how justice is coming.

Jane Got a Gun is merely a decent western that bulldozes over the most conflicted and complicated character dynamics. It’s in such a hurry to ride off into the sunset that it forgets to ask whether these characters were ever meant to have their happy ending.

Jane Got a Gun is now in wide release.