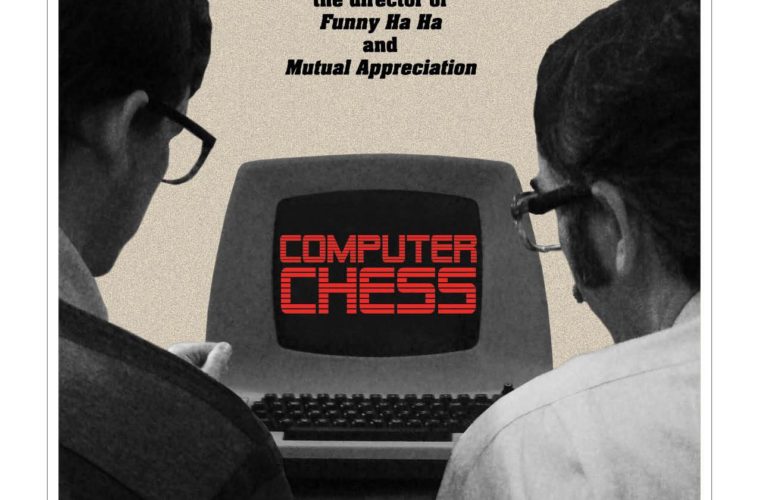

It was over 10 years ago that Andrew Bujalski released his debut film, Funny Ha Ha, and since then, the resulting “mumblecore” explosion is perhaps the most recognizable and distinguished movement in American independent film. Bujalski’s latest film, Computer Chess, at first looks like it will exist outside of the genre’s boundary, presenting itself at first like a time-capsule documentary about a tournament in the early 1980s that pits various computer chess programs against each other, the designers hoping that theirs will get the chance to play and defeat Pat Henderson (film critic Gerald Peary). As the film goes on, however, the computer chess tournament recedes into the background and the individual lives of a few select participants takes the front seat. What emerges is a thoroughly weird and unpredictable film that makes a few interesting observations but also never establishes an agreeable rhythm.

The main players are Michael Papageorge (Myles Paige), Peter Bishop (Patrick Riester), and the tournament’s only woman, Shelly (Robin Schwartz), who serves as a love interest for both. The film jumps between various gags, as Papageorge has to find a new place to sleep every night, Peter is put through romantic trials involving both Shelly and an older couple trying to rope him into a threesome, and a spiritual meeting in the hotel interludes to serve as a humanist contrast to the programmers. Most of this works better in theory than it does in practice as the gags often fail to produce the laughs they work for. In particular, the spiritual meetings fail too often to make their thematic contrast relevant, and most of the conversations about technology, by nature of the film’s setting, are too far behind the times to provoke any kind of interest—“is real artificial intelligence different from artificial real intelligence?” is a stated question that Bujalski does not concern himself with in any serious manner, despite occasionally teasing.

What emerges as a result is not so much a missed opportunity as a tried-and-true one, as conversations satirize our fears of the current technology-boom (it’s stated in the film that computers will be able to defeat humans in 1984, springing Orwell to mind) while also mocking the confidence with which we pretend forecast the future. It’s a tad redundant, and it makes the spiritual meetings useful in addition to unfunny, but it’s also an understated and timely jab considering the role of everything from drones to social media in today’s society. Emphasizing the satire is Computer Chess’ aesthetic, a black-and-white, low-grade analog video that fits the time period but also makes it clear just how much technology has changed since. It may not seem too long that we thought chess programs defeating humans was worth getting worked up about, but since then, fuzzy black-and-white video has made way for cheap, accessible, high-definition video that is employed by amateurs and professionals alike. Indeed, where Computer Chess succeeds the most is as a simultaneous evocation of days gone, a celebration of the digital revolutions humble and occasionally awkward beginnings, and a satire of both our current time and stereotypes of awkward “geeks”; indeed, many of the best jokes make use of these juxtapositions to deliver subtle, intelligent jabs.

It’s unfortunate that less successful gags jar the film’s rhythm; Bujalski wisely keeps chess-playing scenes lean and fringe, realizing that trying to create tension between choppy computer chess games is a nearly impossible task, but those same scenes can be a relief from lesser side-stories or an annoyance when they interrupt the more involving ones. Likewise, when it comes to character, none of our main players are especially interesting, which doesn’t help the film’s haphazard structure. The most drama that will arise is wondering whether the next scene will produce a better laugh than the previous one. When it works, it’s both impressive and delightful. Sadly, it too often falls short, and Bujalski never returns to the more interesting patterns and themes he captured earlier.

Computer Chess is a mixed bag, its effectiveness sometimes changing radically from a scene-to-scene basis, running gags amalgamating and dissolving without a warning sometimes for the better and sometimes not, and a few aesthetic experimentations that become more common as the film goes on are curious, although often times not terribly additive. It’s value, then, is more as a curiosity or an experiment, one that shows but never delivers on its own promise despite repeatedly assuring us that it will.

Computer Chess screened at Seattle International Film Festival and opens in July in NYC.