After hearing about the death of top Orca trainer Dawn Brancheau on February 24, 2010, writer/director Gabriela Cowperthwaite became intrigued by the SeaWorld party line explaining to the media the incident was completely human error. They said it was Branchaeu’s ponytail that did her in—an unnecessarily added appendage for the whale to grab hold of and drag her down. But even if this were truth, could the highly lucrative marine mammal park chain really justify placing no blame on the animal that ultimately took both her arm and life? So, as the world turned its attention on this tragedy and the resulting OSHA case looking to ensure humans no longer perform with killer whales unless separated by a barrier, Cowperthwaite decided to dig deeper and see exactly where everything went wrong.

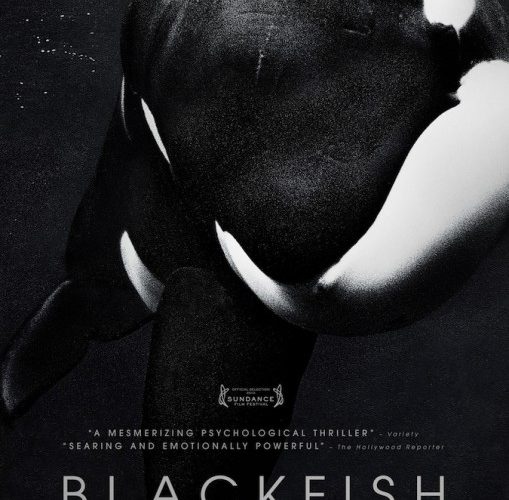

The product of her research—alongside co-writer Eli B. Despres—is the riveting documentary Blackfish. Working backwards from Brancheau’s death, the film not only discovers the circumstances leading to her monstrous assailant Tilikum being in the same pool as her but also provides an unfiltered expose on the theme park itself. While SeaWorld unsurprisingly refused to partake in the project despite numerous attempts—head trainer Kelly Clark‘s testimony is seen from courtroom transcripts, however—Cowperthwaite found a slew of ex-employees to flesh out the emotionally heart-wrenching tale. Trainers who spent years of their lives at the park and ultimately became its face during their tenure speak candidly about the job’s conditions, researchers explain captivity’s effect on Orcas, and horrific footage shows how helpless these beasts can make even the most experienced professionals.

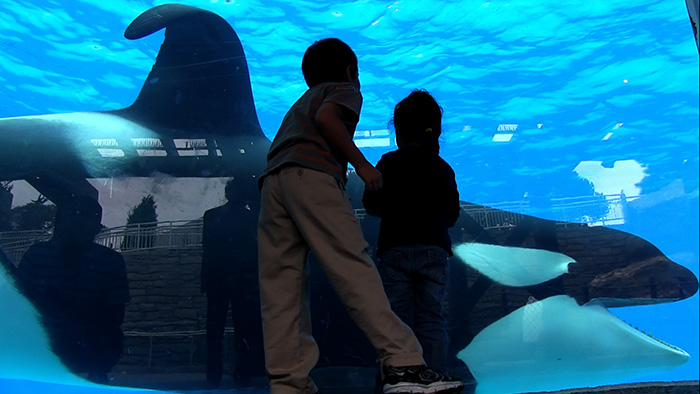

Remorseful divers who kidnapped baby whales for SeaWorld as far back as the 70s explain the communal nature the creatures had as shrieking adults stayed to watch their offspring stretchered and taken away. Scientists tell us how these animals live long lives comparable to humans, have a larger brain with a section that makes them more emotionally conscious than mankind, and live healthily in peaceful familial contingents while in the wild. A highly intelligent species, it’s easy to see the appeal of turning them into performers because they train well and astonish all who see them. But as this level of consciousness allows a strong bond with their handlers, it must also give them the knowledge to understand the conditions of their captivity. Innocent creatures rotting in jails as property, it’s amazing their frustrations didn’t show earlier.

Except that they did. Any violent incident between a whale and its trainer should have raised red flags, but the evidence Cowperthwaite uncovers about Tilikum himself is unreal. The biggest Orca in the SeaWorld stable, his journey from the North Atlantic in 1983 to Orlando that fateful evening in 2010 is checkered at best and at worst a ticking time bomb executives knew was bound to explode. Eyewitnesses Corinne Cowell and Nadine Kallen recount his first victim’s on February 20, 1991 with Sealand of the Pacific casualty Keltie Byrne‘s demise. The story of Daniel Patrick Dukes is told by ex-trainers who arrived at work the morning Tilikum paraded the drifter’s body on his back. And despite any naive love John Hargrove, Samantha Berg, Jeffrey Ventrie, or Dean Gomersall had for the whale, signs of cover-up were seen and ignored by all.

In respect to the families of those deceased, the filmmakers take the high road by not showing any of the gruesome footage that must exist inside a park with cameras shooting every inch of space. Instead we bear witness to the shear strength of these whales via incidents that came a hair’s breadth from turning deadly. We watch trainers grabbed and pulled into the water whether as a playful gesture by an animal that doesn’t realize its own strength or an aggressive maneuver resulting from conditions only it knows for sure. San Diego whale Kasatka is seen toying with trainer Ken Peters for fifteen minutes as he calmly waits in earnest to see whether he’ll have a chance to swim towards safety or not and yet more people arrive to do the job each day.

No matter how much control SeaWorld and their young employees believe they wield, the truth is ultimately black and white. Some like Mark Simmons even think a happy relationship can still be acquired if those in charge take the time to evolve conditions into being closer to the Orca’s natural habitat. If we know they live in matriarchal groups, maybe we shouldn’t allow a male to spend its nights in close quarters with two females who abuse him by raking his flesh with their teeth. If we know how close a bond is built between mother and child, perhaps we shouldn’t blindly separate them and ignore the resulting pained screams and subsequent depression. Maybe a known killer like Tilikum should not only be barred from breeding 54% of SeaWorld’s offspring, but also never enter a tank with humans again.

There are a lot of what ifs and conjecture to wonder how Dawn Brancheau’s death could have been avoided. Whether a result of SeaWorld’s obviously loose notion of morality overall or simply the handling of Tilikum alone, something should have been done. To me the most glaring fact shared throughout the entirety of Blackfish is the utter lack of documented Orca attacks in the wild. Shouldn’t that say something to the idea it’s mankind who placed this stigma of danger upon them? Cowperthwaite wonderfully ensures the people interviewed have first-hand accounts to share through the eyes of a professional who has swan with these creatures and knows their potential. It’s a tragic story for all—including Tilikum—and hopefully this meticulously in-depth timeline of SeaWorld’s history will finally open enough eyes to prevent its continuation.

Blackfish is now in limited release and expanding. One can find more details on the official site.