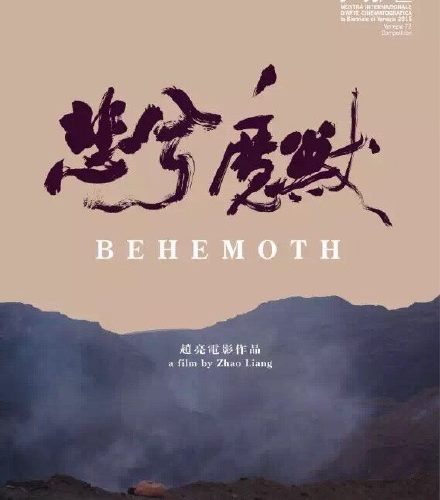

There’s just one thing missing from Zhao Liang‘s visually masterful documentary Behemoth: a before image of what this wasteland of coal and rock used to be before God’s beast was unleashed. That creature — as represented by the industrial machine — devours the mountains of Mongolia, exploding large formations into rubble to be separated by the Sichaun people acting as minions. These citizens become the cause and effect, each job necessary to aid in their survival also proving to be the root of their demise. All this land destroyed; all these innocents dead amongst the ash. What was once a haven of gorgeous landscapes has slowly devolved into a blight of dust and fire, its inhabitants’ purgatorial existence consumed as Hell rises from beneath.

The once-idyllic mountains are, however, represented through visual fracturing as Zhao cleaves the frames of his narration-driven poetry into triangles and trapezoids. Vignettes of spiritual ruminations arrive with a naked man curled in the fetal position, scared and defenseless to prevent what’s unfolding. It’s a gorgeous effect, the diagonal lines shifting the image slightly to allow the shapes of what might have been to try being again. These allow Zhao to remove us from the chaos, placing a wall between what’s happening and the hope that it could possibly still be fixed. Perhaps this figure will stand tall once again, its lesson from God learned and its hubris in eradicating what He built diffused. Its story is told to outsiders who cannot fathom its arduous life.

But alongside these instances come visual cues putting us in the middle of the carnage. Zhao cuts to frames of a bright red or cloudy gray, the colors blinding with conformity before fading into the haze and creating what appeared to be walls but, in fact, is air. Suddenly we’re in the flames, molten metal pouring and shifting as soot and smoke clog our pores. We’re caught within the smog of progress, its dangerous toxicity a means for those off-screen to grow richer and richer while these poor souls return to hovels battered and broken. Behemoth becomes a sort of roller coaster in this way as we alternate between voyeur and participant, our safe haven contaminated by the torturous heat and stifling atmosphere that is easy to forget from afar.

Fertile land has been transformed, the gaping hole that remains spreading farther and farther to drive away anyone who once called it home. We watch herders direct their flock elsewhere, life disappearing with each passing day in the surrounding areas — as it does from within, thanks to pneumoconiosis. The monsters multiply, the metal and machinery digging and pushing as smokestacks elsewhere shoot smoke into the air while statues of sheep mark the past. Idols replace nature everywhere, a cheap replacement for the real thing. There’s even a mammoth Buddha head erected to ask forgiveness as coal and steel allowed man to squander the earth. If only it were all for meaningful progress rather than empty promises of a paradise never to be touched by those working to death.

This isn’t a journey of people. The only movement the living have is towards an afterlife even farther removed from the ghost cities than these mines. Instead we’re watching the earth move to where it never asked to go. Explosions expose resources and they, in turn, are reformulated into a commoditized product. The result travels miles upon miles to help bolster grand notions of clean utopias left dormant and unblemished. Zhao lyrically calls the dirt affixed to the faces of the migrant workers “make-up”; they’re readying for a celebration they’ll never see in an empty world that proves they are sacrificing everything for nothing. The most populated nation on the planet grows smaller and smaller as land dries up and skyscrapers stand idle. It’s a devastating circle of destruction.

And the only words heard come through the carefully constructed narration by Zhao and Sylvie Blum, a tale of man becoming its own means of annihilation. The people are therefore silent participants, our experience left unfiltered besides a penchant to look directly in the camera whether they’re asked to do so or not. Their health deteriorates as the dirt accumulates, one family beaten down by fatigue at the start before shown breathing heavily and nursing debilitating injuries. Each is caught on a ring in Dante’s Inferno, descending further to do the bidding of those uncaring about their plight. This is the cost of our cavalier attitudes towards nature. China’s wasteland may look beautiful onscreen, but it remains a wasteland whose death and exploitation reaches across the globe.

Behemoth enters a limited release on Friday, January 27.