The warning signs start popping up early and often in David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method. They’re revealed mostly through the performance of Keira Knightley, who, playing the patient-turned-analyst Sabina Spielrein, is in fully-committed form. The problem is that, despite all the back tweaking, jaw bulging, and sharply Russian-accented speaking, Knightley‘s work provokes very little excitement or sensitivity. It’s not even that she’s over-acting, frankly — if she were, then that teeth-grating sensation would follow. It’s just that she feels stale.

The film’s overall effect works in a similar way. There’s sufficient period detail, an appropriately talky script from Christopher Hampton, adequate, if modest, lensing from Peter Suschitzky, and an effective Howard Shore score. Even Cronenberg’s direction, if in service if a less-serpentine effort than one may expect, is finely tuned. But the film never really builds to anything. After it cuts to black, there are a series of title cards — you know the kind — that inform us of what fate awaited the three real-life counterparts of the film’s main characters. And they caught me very off-guard — although the film covers several years, not once during it did I think I was supposed to be getting a sense of the entire life trajectory of these characters.

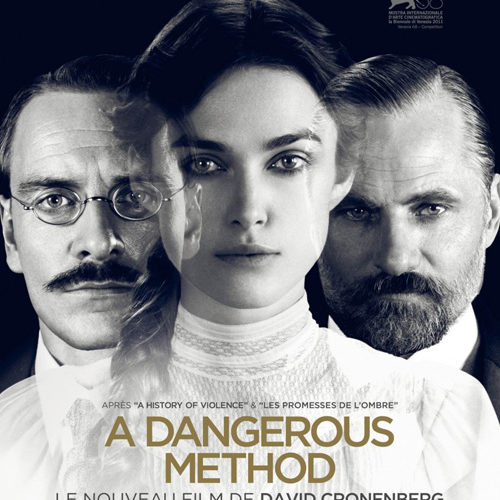

Perhaps that’s because, for all the complex psychoanalysis and detailed digging-ins of this trio, their overall arc, as well as their relations to one another, are disappointingly — and, considering the subject matter, unexpectedly — simplistic. We first meet Sabina (Knightley) when her physical aneurisms are at their peak. She begins treatment under the watch of the happily-married Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender, who’s fine, but, you know, see Shame instead). During their conversations, it becomes a wonder why Sabina herself hadn’t figured out the reasoning behind her symptoms sooner — her father beat her as a child (with sexual connotations, I gather), and she sort of liked it. That seems like a weird and noteworthy period during a person’s life, but apparently she needed Jung’s “Talking Cure” to eventually pull it out of her.

As Sabina becomes more stable, she starts down an educational path herself, trying towards a degree in medicine. Jung, meanwhile, attempts to get in touch with the groundbreaking cigar fiend Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen, best-in-show by a country mile). The two take to each other quite easily — their first conversation, for instance, lasts for about thirteen hours — and a professional, quasi-personal kinship develops. There are minor qualms — Freud is steadfast in his sex-is-the-answer-to-everything mentality, while Jung wants desperately to foster a more liberal approach to studying the mind — but, by and large, the two academics get along swimmingly.

Vincent Cassel, who lights up the screen in a few scenes as sexual deviant Otto Gross (“Never repress anything,” he states, like a broken record), destroys this status quo. Freud enlists Jung to treat Gross for a short period of time, and, during that tenure, Gross’ impulse-oriented lifestyle seeps into Jung’s forehead. Jung begins to question the necessity of his own devotion to his pregnant wife (Sarah Gadon), while simultaneously assessing the extent of his sensual desire for Sabina. Conveniently, though, she makes it quite easy for him, remarking at one point, “If you ever want to take the initiative, I live in that building there.”

The sexual tension that follows, however, is the furthest thing from titillating. (It also makes one question the title — is there truly ever a sense of danger in this film?) And even if that’s not the point — which is debatable, because there are a few watery shots of Jung spanking his confidential lover — it still wears down the level of conflict in the film. It leads to a series of climactic scenes, for instance, that aren’t played out through intense, face-to-face conversations, but through letter writing. It’s fascinatingly ironic — here’s a film that consists almost entirely of dialogue-driven scenes, and when it finally wrenches up the potential for intriguing conflict, the characters are suddenly turned into distant pen pals.

A Dangerous Method is a better-crafted film than I’m making it out to be. But that doesn’t change the end result, which is muted and unaffecting. Hampton is adept at creating wall-to-wall dialogue that sounds profound in the moment — “Sometimes you have to do something unforgivable just to be able to go on living,” “Why should we put so much effort into suppressing our most basic natural instincts?” — but he falls short in fashioning a storyline that moves into the realm of resonance. And I think that lack of vibration might’ve plagued the key performances — as committed as Fassbender and Knightley (the two with the most screen time) are, their line readings leave a surprisingly minimal impression, while Mortensen and Cassel, the two performers relegated to supporting territory, manage to cultivate lived-in, impactful portrayals.

Here is a film that, in a way, recalls the rigidity of Freud’s own style of thought — it crafts in-the-moment propositions that are undeniably thought-provoking, while, in the end, neglecting the necessity of change and dynamism. The film is like a static pulse.

A Dangerous Method is now in limited theaters.