The first two-thirds or so of Nuri Bilge Ceylan‘s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia — his first film since 2008’s Three Monkeys, which earned him a Best Director award at Cannes — are frustratingly hypnotic in their ability to string the viewer along without really depicting any story-furthering events. The film’s premise, revealed slowly and methodically, follows a group of officials — Prosecutor Nusret (Taner Birsel), Commissar Naci (Yilmaz Erdogan), and Dr. Cemal (Muhammet Uzuner) — as they escort two criminals (Firat Tanis and Burhan Yildiz) through the swerving, winding, hilly roads of rural Anatolia.

The crooks have confessed to a murder that occurred a few days ago. Problem is, they were inebriated at the time, and can’t seem to remember where they buried the body — and it’s hard to blame them whole-heartedly, considering the near-perfect symmetry of every pitstop they encounter. It’s nighttime, too, which makes matters worse, though the situation proves a welcome obstacle for cinematographer Gökhan Tiryaki, who completely soaks up the chilling nighttime atmosphere with frames that are often guided by nothing more than the dim glare of the brigade’s vehicular headlights. Ceylan‘s own restraint, with respect to the atmosphere, is no less respectable — he relies on natural elements, particularly the incessant noises of barking dogs, howling winds, and crackling thunder, to develop the eerie surroundings.

The nighttime sequences are crucial in enhancing the philosophies of these characters, even if they may seem tangential at the exact moment they occur. After repeated instances of Naci berating his two suspects for their navigational inefficiencies, it’s not hard to question the relationship of a later dialogue scene between Nusret and Cemal that documents the apparently out-of-left-field story of an unseen woman who, to Nusret’s knowledge, accurately predicted the exact date her death would occur.

The film’s latter portions take place in the sunlight of the following day, and although Ceylan isn’t too keen on bringing everything in the story full-circle — there are still elements in the film left unexamined, and it’s irrefutable that the runtime could’ve been shortened (though I have no personal complaints regarding the duration) — there’s a substantial emotional bridge between the film’s two halves that culminates in a curiously and unexpectedly moving finale.

That a film this bare in plotting and storytelling can carry such an emotional heft is certainly a product of Ceylan‘s calm, observant approach, but it would be an injustice to not cite the brilliant work of the entire cast as well. The most complete portraits in the film are of the three principal officials, much of which is due to the heavyweight performances put forth by each of these performers. Each role is infused with a back story of some sort, but the most pressing information is translated more through the actors’ faces than the words they’re actually saying.

There are two sequences late in the film, both extended and flooded with dialogue and reaction shots, that make the trying journey worthwhile. One is an exchange between Nusret and Cemal that affords the two actors with ample opportunity to get inside the skin of their characters — and they do exactly that. The other is an autopsy scene — longer than you might imagine, like most scenes in the film — that singles out Cemal. In effect, his character arc is constructed within this single scene, but it’s executed with a pristine level of subtlety, and the effect is palpable.

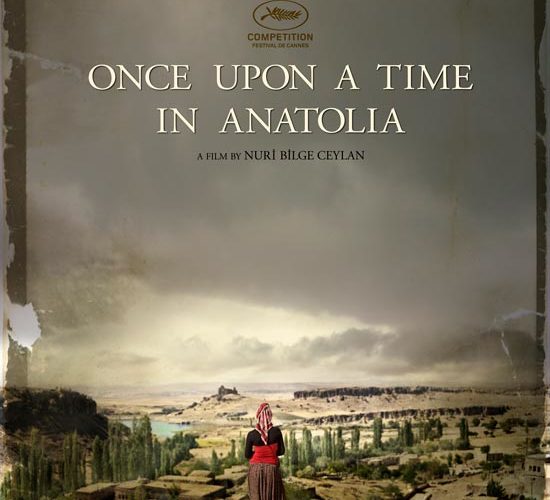

Ceylan spends most of film capturing the Anatolia landscape in eventless, extended frames, beautifully realized by Tiryaki‘s lensing. And even though it’s obvious from the outset that the film is too well-made to suspect that there might not be a point to Ceylan‘s methodical madness, the emotional heft of the closing sequences still comes as a shock. Certain films are often praised for their economical storytelling — for conveying as much as possible in as little time as possible. Here, Ceylan happily tears that approach apart. He spends 157 minutes covering an investigation that doesn’t exactly merit such attention. The characters do, however, and somehow, someway, this bloated structure paves the way for an abnormally enlightening character study of three men, all of whom are wounded, dynamic, and undeniably human.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is currently playing at New York Film Festival and a 2012 release in the US is planned via distributor The Cinema Guild.