Arnaud Desplechin’s My Golden Days bears some superficial similarities to national compatriots Eric Rohmer and Olivier Assayas, two directors who tend to make films about beautiful, young, artistic people going through tough times that results from some combination of inner conflict, government, and the sensibilities of other, equally fashionable people. Of course, these directors aren’t especially alike; Rohmer is concerned with the way a person’s desires and actions — or their ideas and realities — may conflict, particularly in concerns of (heterosexual) love; Assayas’ characters drift apart and float together through means largely outside their control, or at least through means incident rather than integral to their decisions. (His protagonists are generally undone by loneliness and isolation, whereas Rohmer’s encounter trouble when they interact with one another.) My Golden Days contains much of Rohmer’s hapless romance and Assayas’ internal depression, but it is temporally expansive and deploys new tricks at every turn in a way that the films of Assayas and especially Rohmer — whose work takes place in subtly but rigorously established worlds — never would.

The film’s French title, which translates to something like Three Memories from My Youth, is more fitting. We see Mathieu Amalric‘s Paul Dedalus (the same character he played in My Sex Life…or How I Got Into an Argument; Quentin Dolmaire is the primary lead) having unhappy interactions with his father, his school trip to Russia — in which he and a friend go off-the-grid to help out those in need — and through the years with Esther (Lou Roy-Lecollinet), the love of Paul’s life. The last of these takes up almost three-quarters of the film.

The first is mere backstory, but it sets the grim-fairy-tale tone that remains throughout. The second, slightly longer, is crucial in another way. My Golden Days unfolds as that story reaches its end, with Paul being questioned on his return from Tajikistan (where he has been doing anthropology work) to Paris, because an Australian with his credentials has been found. As it turns out, Paul left his passport in Russia to help his “double” escape, and the idea of a double and an alternative possibility haunts Paul’s regretful nostalgia. Paul narrates his further tales from then on in a sort of Proustian conceit, and the voiceover(s) is / are accordingly instilled with more than a twinge of regret and a reminder of the present moment’s ephemerality. Desplechin swings wildly through time, days or weeks or years being tracked only incidentally, and the moods and beliefs of Paul, Esther, and the other central characters — as well as the tone of the film itself — oscillate from scene to scene and act to act.

What elevates My Golden Days above a sort of cookie-cutter, exuberantly “French” lost-love story is Desplechin’s deployment of the voiceovers (one of which he himself does), which will disappear for long stretches of time, only for a new storyteller to take over later, as well as his startling control of mise-en-scène and sound. “Control” seems to suggest stylization, which is not the case, but “lived-in” is not quite right either; rather, there’s a natural expressiveness to colors, light and shadow, music, and even the voiceover that makes each moment distinct and memorable. While childhood may be a fairy tale, the school trip is something of a thriller — moodily lit, drained slightly of color, shifting in location to often to establish a “home” with distinct decor. In “Esther,” pop music, clothes, and things like photos and postcards abound, all subtle indicators of time gone by; fashion and music are of their times, of course, and nothing briefly tunes out reality like a postcard or a picture.

That Desplechin takes such care of every aspect of his sound-image means that even if scenes and plot developments are predictable, the way they are presented is not. Desplechin refuses to shoot them predictably, thereby encouraging alternate readings of particular scenes, especially with regard to point-of-view. In particular, he lets Roy-Lecollinet act: her cries, laughs, and yells attract the camera for an extra couple seconds, with the camera a little closer than it is to other characters, even letting her directly address the camera to read letters. It’s no doubt a result of Paul’s infatuation and memory, but it also puts the film in constant conflict with its own solipsism.

In a bad or mediocre coming-of-age movie, love, sex, parties, studying, and trips to college / back home are symbols of particular feelings; in decent or good ones, they might be convincingly evoked moments of an individual’s life. In My Golden Days, they tend toward the latter, but push to something even bigger — tinged with, even haunted by the reality that these moments exist outside the individual. A coming-of-age film with a broader perspecttive is always welcome, and it paradoxically makes this as evocative and convincing a portrait of youth as the best work of François Truffaut.

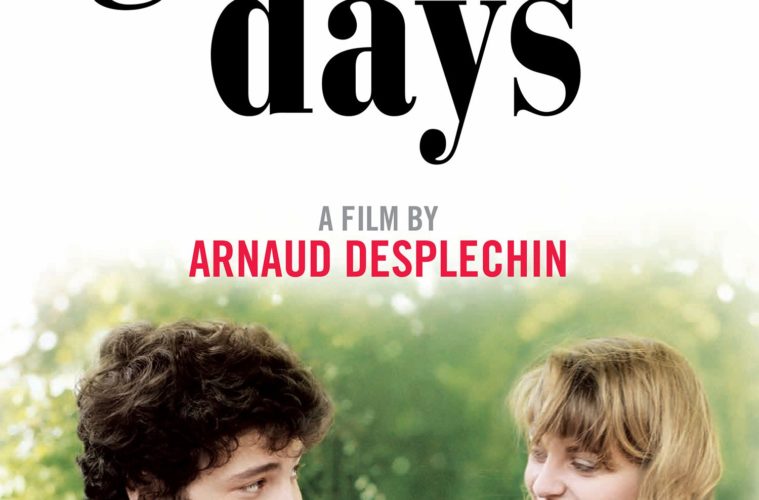

My Golden Days screened at the New York Film Festival and will be released early next year.