To draw an easy comparison, Captain Phillips is this year’s Argo. Ben Affleck‘s Best Picture winner, though a highly suspenseful thriller, was also one in which very few bad things actually happened. There’s no doubt it was a life-or-death situation for all involved, but, with very few exceptions, things went according to plan — and, as the film ended, America was not just great, but exceptional, having successfully pulled its citizens out of hostile territory with no casualties. It’s a good film, but complex politics were not on its checklist — as its problematic treatment of extensive Canadian involvement would tell you.

To revise, then, Captain Phillips is this year’s Argo in terms of thematic character, although it doesn’t deliver with the same strength as that spiritual predecessor. It’s another true story of America saving its people from dangerous situations and another rousing portrait of American exceptionalism, but it depicts as much without a script that can bother to expand upon the important details. There are only a couple of lines that reference circumstances which, in Somalia, have led to piracy, and the country’s struggle is never made palpable — there isn’t anything even close to a B plot in this film — while, similarly, Richard Phillips’ family is never seen in its entirety (his wife, played by Catherine Keener, is only glimpsed very briefly), yet the script is still littered with moments about them. Screenwriter Billy Ray makes the classic mistake of telling instead of showing.

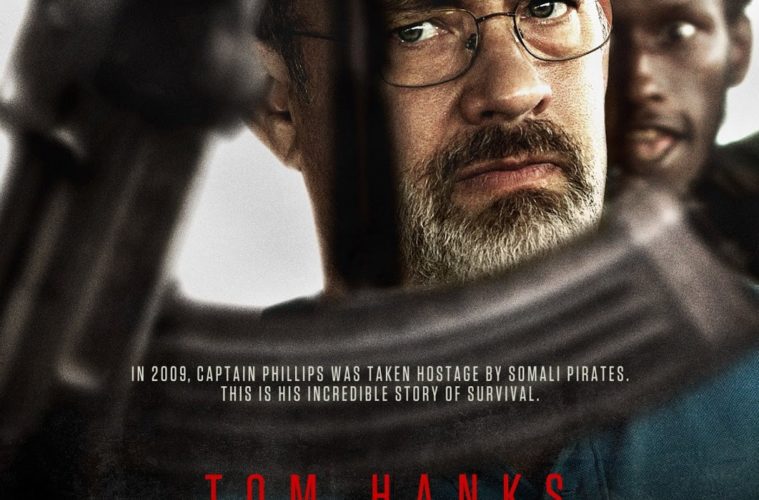

On the other hand, its flair for suspense works in exactly the opposite fashion as Affleck’s handling affected Argo. In that film, the plan always worked; in Captain Phillips, it never does. The conflict between Phillips / his crew and the pirates is a constant tug-of-war in which nothing ever goes right and stays that way for either party, suspense thus generated largely from the knowledge that something could go incredibly wrong or incredibly right at any moment. As a result, the film — which recounts the 2009 hijacking of the Maersk Alabama at the hands of Somali pirates — is a thrill almost from the beginning. The pirates are introduced immediately after a brief opening scene, and the first meeting between Phillips (Tom Hanks) and his captors, led by Abduwali Abdukhadir Muse (Barkhad Abdi), follows shortly thereafter. From there, the film never lets up — whether it’s gunfire, a high-stakes game of cat-and-mouse, or simply a matter of waiting.

That is to say, this is exactly what you would expect a Paul Greengrass thriller to be. He pulls off his usual style: shaky camera is employed during action scenes, while a more conventional, well-edited shot-reverse-shot style pervades the less-dangerous environment outside Phillips’ boat. Strangely enough, though, he never lets the two major set-pieces — set aboard an enormous container ship and a minuscule lifeboat — come alive. Almost every scene takes place in merely one location, and as a result the cruiser never feels large enough — even as pirates struggle to navigate it — while the cramped lifeboat only occasionally feels claustrophobic (usually when guns are being waved and people are yelling). Likewise, the long tracking shots of the sea never establish any effective juxtaposition with the slow, dark lifeboat, as Greengrass so clearly intends.

Foremost keeping Captain Phillips alive is its clever dialogue. The way Hanks curtails his speech to subtly give Phillips’ crew an advantage — e.g. his sly note that one of the pirates is barefoot — is a joy to watch; Ray’s screenplay never waits so long for payoff as to let the viewer feel more clever than they ought to. Later, the mind games that Phillips plays with Muse and his crew prove to be calculated risks — attempts at small, advantageous steps that also provide a subtle examination of what “Captain” really means. It’s not only playing with dynamics of power, but subtly recalling the film’s opening conversation and allowing a viewer to connect the provided dots. As is only appropriate for a story in which time and tension constantly threaten to send characters off the rails in a violent manner, details become increasingly important as action progresses.

Hanks, meanwhile, is a revelation all over again, giving his best performance in at least a decade, possibly two. Simply put, Captain Phillips would not function without Hanks. Whether he’s doing basic captain duties, corralling his crew to ward off pirates, playing a duplicitous helper dropping subtle hints to his crew, or a frightened man carefully attempting to create dissent among the ranks of the pirates, Hanks is always convincing. The actor particularly excels in his line delivery, striking a difficult balance between gaining trust with some while simultaneously alienating others.

Forrest Gump was a convincing body performance, yes, but less emotionally demanding, while Cast Away, though captivating, didn’t demand as much versatility; the range Captain Phillips demands exceeds these (and other memorable Hanks roles) by a notable degree without sacrificing performance. All credit in the world to Abdi, too, who more than holds his own to generate sympathy, despite having a very underdeveloped character; it’s only the script that prevents questioning (rather than propagating) American exceptionalism, but Abdi nearly questions it all on his own. Captain Phillips may be a thinly scoped story with tried-and-true themes, but the acting turns it into a surprisingly captivating story of heroism.

Captain Phillips premieres at the 2013 New York Film Festival, and hits theaters on October 11.