The film adaptation of a satirical novel about American soldiers returning from combat to be celebrated at home by a people that can never fully appreciate their sacrifice — as directed by the incredibly earnest Ang Lee. They feel like strange bedfellows, and the result, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, proves both messy and inspiring.

Newcomer Joe Alwyn plays Billy Lynn, a decorated soldier back from Iraq. He and the rest of his Bravo unit are set to be celebrated and showcased during the halftime show of a Thanksgiving day football game in Dallas circa 2004. For being filmed at 120 frames per second and ostensibly / ideally presented at 4K resolution and in 3D (though it appears only two U.S. theaters will be able to handle all of that), the intention here is to be immersed in every detail of Billy’s experience at home and abroad.

And while there’s much to admire in this technical push, it’s only affecting in fits. For over a century, cinema has commonly been filmed and presented at about 24 frames per second. There’s a certain lag — or gloss — that comes with this frame rate, as the human eye can see far more frames per second (fps) than twenty-four. And it’s just that lack of lag or gloss that comes with 120 fps, making for a visual hurdle still too high to clear. Not surprisingly, this technical innovation is most effective on the football field and on the battlefield, both sequences paralleled throughout the picture’s second half.

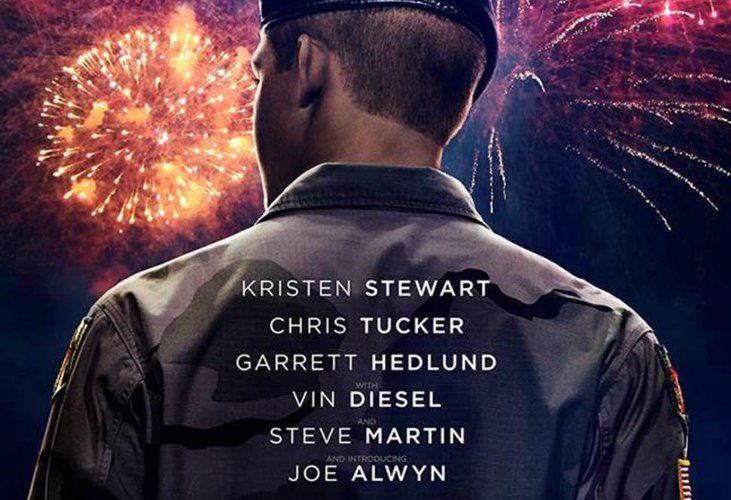

Alwyn is surrounded by an impressive supporting cast, including Kristen Stewart as Billy’s sister, Kathryn, who’s determined to stop her brother from going back over there; Chris Tucker as a Hollywood producer determined to get a movie deal for the boys; Steve Martin as the semi-villainous, Jerry Jones-lite football owner; Garrett Hedlund as Billy’s hard-edged commanding officer; and, finally, Vin Diesel as Shroom, a Bravo sergeant whose death haunts the film.

While the unit is simply trying to make it through the strange and stressful game-day proceedings, rendered nicely in a particularly memorable press conference scene, a budding romance develops between Billy and Faison (Makenzie Leigh), one of the Dallas cheerleaders. Alwyn and Leigh’s scenes together feel the most genuine for their lack of ingenuity. Both Billy and Faison are playing roles, their mutual expectations built on societal stereotypes of the masculine warrior and the doting, pretty future wife. Leigh finds depth in these moments, adding sardonic beats to some on-the-nose dialogue.

The screenplay comes from Jean-Christophe Castelli, adapting Ben Fountain‘s novel, and it is intensely blunt. Though this, of course, appears to be intentional. Most of these characters recite the themes and conflicts in dialogue, saying things such as, “Americans are children who must go somewhere else to grow up, and sometimes die,” along with, ‘Talk is cheap, but money screams. This is our country, guys. And I fear for it.” Though the message is clear, it too often lacks the bite of war-time satires that have come before. Certainly the “realness” of what’s being presented, thanks in part to the increased frame rate, does not always mesh well with what’s meant to be extreme versions of the world we live in and the people we are.

It’s a struggle Lee seems to be wrestling with from start to finish. There have been a thousand war movies exploring who we send to fight our fights, how they come back, and what we can do to get them healthy. Some of what’s explored in Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk feels like an expansion on the subject, asking questions about what it means to truly appreciate our troops and live with all that’s made to happen in battle — an emotion momentarily, and beautifully, captured during the “Star-Spangled Banner” at the movie’s halfway point.

In trying to suss out just how much we owe these brave men and women, Lee offers up plenty. But it’s still not quite enough.

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk premiered at the New York Film Festival and will enter theaters on November 11 with a wide expansion on November 18.