The fact that America’s past isn’t without its horrific nightmares of misguided violence and oppression shouldn’t be lost on anyone, especially not with everything that’s going on here today. Our history runs red with the blood of men, women, and children who fought to survive against a force that thought themselves superior because of the color of their skin. White Europeans staked claim upon their arrival, killing the Native Americans with gunfire, alcohol, and disease before chasing them off west. They brought slave ships full of Africans as unpaid laborers, property to be bought and sold. And after the latter won their freedom as a result of the Civil War, the former remained in invisible chains—the discovery of gold in the Black Hills eventually tightening them further.

Scott Cooper’s Hostiles (based on an unrealized manuscript by the late Donald E. Stewart) isn’t about that fight per se. Instead he focuses on the aftermath—the cost. The Great Sioux War of 1876 ended with a lot of bloodshed courtesy of the American aggressors seeking to buy land they were ready to steal and the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne who stood up against their greed. It of course ended in surrender and the formation of Indian reservations, leaving tensions ever more volatile with racism and hate brimming over until Comanche tribes were wreaking havoc on scalps as US soldiers hunted them down. The Wild West was in full force, the fight never quite ceasing its carnage. By 1892 you have to imagine fatigue had set in.

It’s here that Cooper’s tale begins with weary men who’ve run from their demons too long standing on the cusp of what will surely be a haunted retirement. With all they’ve seen and all they’ve done, the party line of “We were doing our jobs” can’t keep the guilt at bay forever. Now that these men are two decades removed from the war, clarity sets in. Orders are no longer a good enough excuse. Calling the enemy “savages” starts to take on deeper meaning as they acknowledge the fact they committed the exact same crimes on humanity. To therefore look upon the enemy with the memories of what they did is to peer into a mirror. While you were doing your job, they fought to keep their homes.

What better way to show this complex emotional and psychological dynamic than to have Captain Joseph J. Blocker’s (Christian Bale) final ordered tasked be chaperoning one of the men he imprisoned seven years prior (Wes Studi’s Cheyenne Chief Yellow Hawk) back home? President Benjamin Harrison was allowing Yellow Hawk’s dying request despite his former land now being the property of some unknown white prospector. The whole thing was a publicity stunt anyway, a means to an end painting the current administration a compassionate one. But that didn’t lessen Blocker’s rage. It didn’t help him forget the friends Yellow Hawk killed with his own hands. An order is an order, though, and Joseph has made it clear he does his job. It’s why he’s trusted with this arduous task.

That sounds like a pretty effective plot because it is. Force these age-old combatants together and watch what ensues. Will they be able to trust each other when the moment arises where they must? Will their honor compel them to understand how similar they are and how intrinsically bonded they will remain no matter what end is coming? Blocker will have his team (Rory Cochrane, Jonathan Majors, Jesse Plemons, and Timothée Chalamet) and Yellow Hawk his family (Adam Beach, Q’orianka Kilcher, and Tanaya Beatty). They will eventually have Comanches on their tail, a murderous criminal (Ben Foster) to shelter, and fur trappers to combat, so it won’t be long before they are faced with experiencing each other’s humanity when standing side by side together against a common foe.

Unfortunately, Cooper falls into some damning narrative traps in the process. First is the introduction of Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike) with a tragic backstory of convenience to the plot. Next is an ample body count that never feels authentic since every fight fatefully leaves Blocker unscathed as though God is teaching us about the ever-weighty idea of white guilt through him. And last is the ham-fisted series of tasks manipulated to continue where the previous left off. It’s one thing for a single man to face so much violence in one fell swoop, but it’s another to present everything as trials that inherently make everyone else into a pawn. We need Blocker and Yellow Hawk to be equals, something that can never happen if only one is expendable.

And we realize this truth in the opening prologue depicting a remorseless band of Comanches as they cut through an innocent family. It’s like Cooper is trying to coercively paint Native Americans as his villains so we can understand Blocker’s initial refusal of his commanding officer’s order to take Yellow Hawk to Montana. He’s laying it on too thick so that we may fear the Captain’s prisoners despite the entire endeavor hinging upon our ability to trust them as humans. It makes us wonder if Cooper is merely increasing his body count for the sheer fun of it because we don’t need a blood-soaked reason for Comanches to hunt their party—they’d do so anyway. We also don’t need Rosalie to join them except to add another mirror.

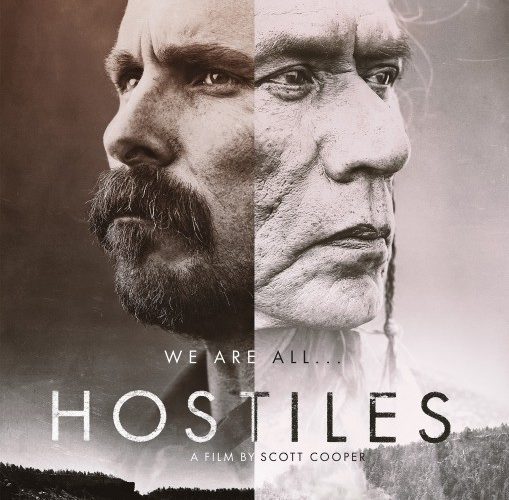

Every single action proves overt to the point of superficiality with Hostiles becoming less introspective drama than unsubtle parable. The demons grab ahold of everyone, tragedy strikes at each turn, and Blocker is sadistically told how “good” a man he is despite his insides burning in a fire of absolute shame. He’s relentlessly punished with a revolving door of companions that ensure he cannot forget what he’s done and new situations able to bring out the monster behind his soft-spoken demeanor and polite sense of chivalry. We are made to see the duality of man as half compassionate soul and half fiery wrath of God. Both are necessary to survive this journey and bring these mortal enemies at its center closer once they realize their motivations are identical.

But while the plot’s ham-fisted nature prevents us from caring about anyone but Blocker as more than the next character to die, it does present Bale a role of immense feeling. For all the film’s faults, I could still recommend it for his performance alone. It too toes the line of excess with his being thrust into so many melodramatic circumstances, but Bale is never anything but authentic within each. We understand his internal struggle, the love for those he fought beside and lost, and the embarrassment of remembering the pleasure he felt pushing knife into flesh. His Blocker epitomizes the soldier trained to kill who’s suddenly pushed back into society. He’s a flawed man who knows the only person that truly comprehends his pain is his enemy.

Hostiles opens in limited release December 22nd.