In Arnaud Desplechin‘s Jimmy P.: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian, the French director makes his second leap toward the English-language realm (following Esther Kahn) to varying degrees of success. Based on the true story of a Native American suffering from a series of debilitating headaches, the film is adapted from a text by the actual therapist who treated the titular Plains Indian. Much of the focus is centered on how clinical psychiatry differed in techniques towards the end of World War II. It’s a bit reminiscent of something like The King’s Speech, which also focused on the relationship of therapist and patient, albeit in completely different circumstances. The problem with Jimmy P. is that despite being intensely focused on the relationship between these two characters, the film never really amounts to much and feels meandering and dull.

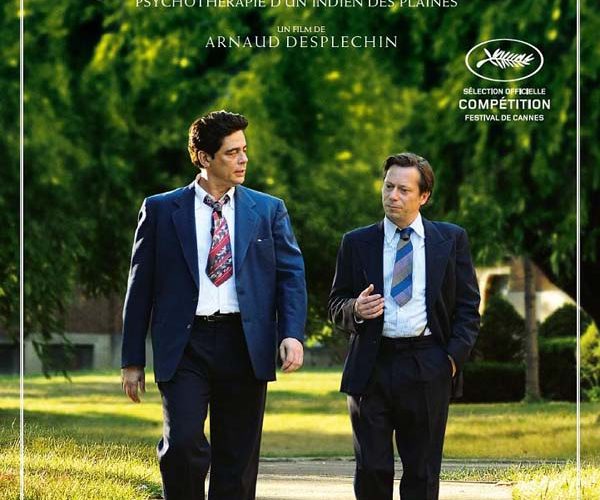

Benicio Del Toro plays the titular character Jimmy Picard — who, after returning from the war with a fractured skull, is suffering from numerous symptoms including dizziness and temporary blindness. When his sister takes him to a military hospital in Kansas, doctors there are perplexed by what is causing pain for Jimmy when he seems to be in fine psychical condition. Fearing they might be missing something due to his Native American background, they recruit Georges Devereux (Mathieu Amalric), a French psychoanalyst who specializes in Native American culture. What ensues for the remainder of the film is Georges treating Jimmy by simply talking to him about his issues and analyzing his dreams.

If all this seems clinical, that’s because it is — and, for whatever reason, the film cannot seem to treat itself of its own malaise. More curious is the reasoning in choosing the material, which does not particularly lend itself well to the medium of cinema. While certain elements do work within the context of the setting, there is a lack of conflict that sets the film adrift, wandering aimlessly towards a somewhat predictable and inevitable conclusion. Del Toro does an admirable job of portraying the dialect mannerisms akin to Native Americans and, in turn, lending believability to his ailments, while Amalric’s neurotic Devereux often feels like a caricature of what one might expect from a slightly eccentric French psychoanalyst.

All in all, it is the decision to choose this source material that is perplexing. Presumably Desplechin was taken aback by the book and felt compelled to turn this story into a film, yet the material does not jive with the somewhat aloof direction. Its strongest element is a convincing portrait of psychotherapy in the early 50s, making for a compelling enough reason to seek this film out if you are interested in this practice. However, for the rest of us, Jimmy P. will leave you wondering what could have driven someone to want to make this film in the first place.