Before surrealist legend Luis Buñuel found himself directing multiple films a year during the 1950s on the way to creating French classics like Belle de Jour and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie in the 60s and 70s respectively, he became a persona non grata when it came to European benefactors thanks to his feature debut L’Age d’Or labeling him a heretic and almost getting his producer excommunicated by the Pope. With Salvador Dali at his side, the Un Chien Andalou filmmaker was dismissed as a provocateur nobody was willing to risk ruining their reputation over if he continued driving his own into the ground. Buñuel’s only chance of getting something new off the ground was his avant-garde artist friend Ramón Acín serendipitously winning the lottery.

It doesn’t get more surreal than a drunken night on the town lamenting his poor luck with someone who’d understand leading to a windfall that would send them both to a remote village in Spain near La Alberca named Las Hurdes. Acín (Fernando Ramos) would make good on his lark of a promise when his numbers came in as Buñuel (Jorge Usón) recruited French author Pierre Unik (Luis Enrique de Tomás) and cinematographer Eli Lotar (Cyril Corral)—who just happened to give him the book that inspired the desire to shoot a short documentary with altruistic intent as a means of securing financing—to assist in this adventure to a civilization untouched by the outside world. It’s this fateful chain of events that would alter Buñuel’s trajectory forever.

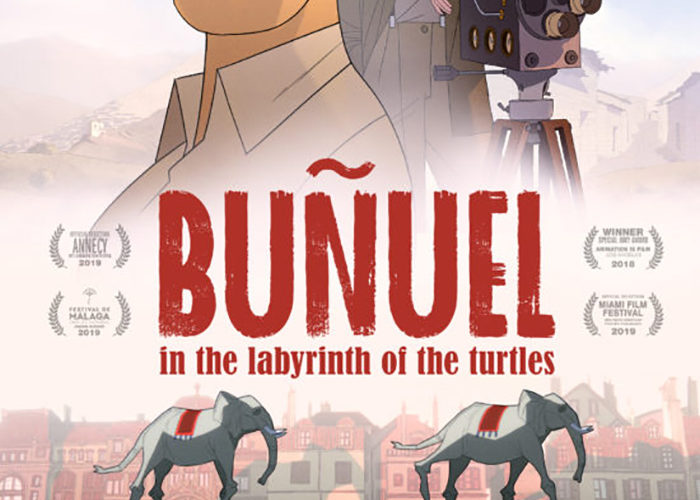

More than merely an anecdote, however, director Salvador Simó and co-writer Eligio R. Montero have drawn up their own film to delve into Buñuel’s mind as he struggled to escape the shadow of Dali, a wealthy upbringing sans paternal love, and the uncertainty of who he wanted to be as an artist. Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles therefore provides as much insight into the often-manipulated “truth” of what this quartet shot in Las Hurdes as the filmmaker’s nightmare-fueled psychology threatening to destroy friendships and his career in pursuit of fame. It was when Buñuel had no money to create that the potential humanitarian good of this project captivated him. Once there, though, its potential to augment his name grew.

These fantasy moments inside Buñuel’s mind are where the choice to use animation comes in because Simó is able to seamlessly throw his subject onto a street overrun by stilt-legged elephants or into a scenario with a half-naked, floating woman transforming into the Virgin Mary. He moves from these dreamscapes to the harsh reality of death and poverty his characters are documenting while also injecting clips from the actual Las Hurdes—flipping back and forth between the real footage and the cartoon reenactments of how each was captured. Simó isn’t afraid to shine Buñuel in a harsh light either as his incredulity and ego push his collaborators to the brink of quitting once the locals start to see their “savior” as a vain man mocking their culture.

This area is where parents should be warned about the lack of rating because there’s a lot of death involved. Where the aforementioned naked woman and a couple unnecessarily tasteless jokes of a sexual nature (one such example being when Pierre and Eli lust over a maid before laughing unprovoked that she must be “helping” her employer with more than the cleaning) push boundaries, Buñuel’s fascination with animals dying as a means of portraying this place’s burdens can be rough to experience no matter what your age is. After hearing that goats fall off cliffs and donkeys get killed by bees, Luis will do whatever is necessary to capture both tragedies on film. He’s here for his vision of the truth more than the truth itself.

It’s an interesting glimpse at his process with Buñuel doing despicable things alongside beautiful ones. Simó takes pains to contextualize this duality as stemming from the artist never having received the love he craved from his father and how that pain re-enters his mind when orphans reach out to be hugged or children are left to die in the street. There’s this desire to be hardened to the unrelenting darkness of life like his dad was, but that mindset only pushes his humanity and the original reason he came to Las Hurdes to the background. At a certain point Buñuel must decide whether his film is to be about what he needs it to be (exploitation) or what it should be for those he’s filmed (anthropology).

Simó has an added purpose of his own as his work soon reveals itself to be more than a look into Luis’ past. This story is ultimately as much about Acín as Buñuel because he’s by his side every step of the way. Nothing happens without Ramón’s money and who knows where his friend’s career would have gone then? Considering the terrible circumstances soon facing Acín and his wife during the Spanish Civil War, highlighting his legacy with this remembrance should elevate his name for those unfamiliar (like myself). He ends up being the conscience Buñuel desperately needs to find meaning in his art beyond confrontation. The opening scene depicts a debate questioning whether art can “change the world.” In many ways Acín’s presence reminds Buñuel how.

Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles opens at the Quad Cinema in NYC and Nuart Theatre in LA on August 16 before expanding.