The Owens family is at a nexus point of chaotic emotions, troubles, and fears thanks to the start of new chapters in their respective lives. Mom (Katherine Wessling’s Ann) has officially accepted what everyone else already had: a battle with depression. Burgh (Ben Kaufman) recently started seeing someone (Sarah Haruko’s Cassie) he’s afraid to reveal to the family due to her having a past history with his younger sister. She (Alexandra Clayton’s Annie) is ready to pop thanks to hers and husband Paul’s (Ricardo Manigat) first child, making it so they will need their spare room back. The current inhabitant of said room is eldest sibling Cecilia (Christina Wright) who’s sans job, sans love, and uncertain of finding either again. And Dad (Peter Jensen’s Tim) bought a donkey.

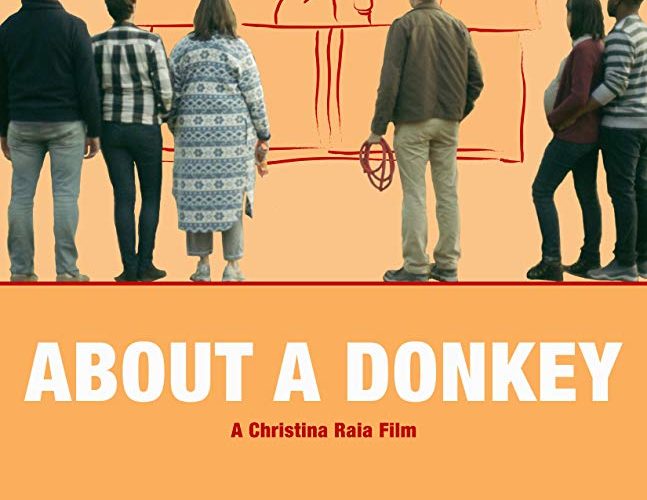

You read that last sentence correctly and the family is equally flabbergasted with the purchase. Director Christina Raia and writer Kelsey Rauber’s film About a Donkey is therefore very much about said animal even if TG’s deep brown eyes are missing for a majority of the runtime. She’s a catalyst of sorts — a metaphorical representation of what’s missing in their lives. Her arrival lifts Tim’s spirits higher than they’ve been in years while causing Ann to jealously wonder if she’s been replaced. Annie laughs despite being more than willing to help (she’s on maternity leave and itching to get parenting underway). Cecilia and Burgh scoff with a blanket statement about being perpetually “busy.” When TG goes missing, however, they discover just how much everyone needs each other’s support.

This is a group built upon sarcasm and witty, off-the-cuff verbal jabs of deflection they’ve deluded themselves into believing are actually signs of empathetic affection. Let’s face it — we cope with things better when humor is involved because a good laugh masks the pain the suffering party endures. So while it’s funny to hear these kids diminish their mother’s ailment (probably because they diagnosed her long ago) and to watch her anger rise until it wouldn’t be far-fetched to assume she killed TG, Ann is hurting. She does crave the attention Tim is now providing the donkey instead. She wants her kids to be as involved in her life as Cecilia is with their grandmother (Ellen Graff’s Farrah). It’s tough, though, when so much is going on.

We gravitate towards those who understand us. As a lesbian, Cecilia sees a kindred spirit in her grandmother since she found love post-widowing in the form of a woman. Annie aligns closest with her father as the family’s nurturer she hopes to become. And Burgh seeks out Cecilia as his confidant thanks to a shared sardonic wit and superficial indifference used to cut through the emotion-filled atmosphere cultivated by the rest of their bunch. Ann is therefore the odd person out. There might not be anyone to blame more than herself and her refusal to leave the house or shake free from her frustrated malaise, but that’s no excuse for the others to stay at arm’s length. As TG reinvigorates Tim, though, Xanax breathes new life into her.

The film becomes an awakening for each one. TG’s disappearance so soon after her arrival exposes how delicate happiness can be as the joyfulness Tim possessed is gone in an instant. They each find themselves struggling to accept what has sucked the respective life from them too. Cecilia is wrapped up in her fear of rejection despite how obviously interested Farrah’s latest nurse Jordan (Elisha Mudly) is in her. Burgh is scared to let Cassie into their circle because he’s too afraid to ask why she and Annie have so much animosity between them and thus risks his relationship through inaction. And Annie is so pure at heart in her desire to make the rest feel content that she sometimes acts too impulsively for everyone’s good.

It’s events like hers that make what’s onscreen so endearing and relatable — the goody-two-shoes proving she’s one of this motley crew after all. So while the Owens family might not have any earth-shattering issues to contend with, they’re still dysfunctional in a first-world sense of needing support and reassurance to prevail with courage despite inner monologues constantly telling them why things will never work. Their insecurities bind them in such a way that they are blind to reality. They must receive external pressure to wake them from their self-imposed psychological prisons whether through tough love (Cassie to Burgh), welcome eccentricity (Farrah to Cecilia), or a sickening abundance of authentic optimism, hope, and compassion (Paul to everyone). All it takes a little nudge in the right direction.

Getting back on track means different things to different people, though, and may take longer for some. Tim might only need TG’s face to warm his heart, but Ann desires a combination of being seen, being heard, and perhaps a bit of cold-blooded murder after all. Their children are then overly apologetic in ways you probably hate because the same could be said about you. So while Raia and Rauber have crafted a film to entertain on its own merits, About a Donkey also possesses the potential to open your eyes and recognize you can overcome whatever roadblocks are in your way too. Love, family, and even strange pets have the ability to make you whole if you’re willing to be vulnerable enough to let them.

About a Donkey screens at the Buffalo International Film Festival on October 7.