The opening titles of Gianfranco Rosi’s new documentary Fire at Sea state that 400,000 migrants have landed on the Sicilian island of Lampedusa in the past 20 years, having braved the perilous voyage across the Mediterranean from Africa, and that 15,000 have died. Shortly thereafter, we see an elderly Italian woman preparing lunch in her kitchen. The television is playing somewhere offscreen. The lady chops her vegetables while paying only casual attention to the TV, which is broadcasting a news report on a recent shipwreck that cost the lives of the many migrants onboard. “Poor souls,” she says mechanically and without looking up. This short scene perfectly encapsulates the current frame of mind in Italy vis-à-vis the migrant crisis and the reason why films such as Fire at Sea are necessary. And while Rosi certainly manages to jolt the viewer out of complacency, his strategy towards this end is so ethically dubious as to border on repellent.

In a manner reminiscent of his previous documentary feature, 2013’s surprise (and unmerited) Golden Lion winner Sacro GRA, Rosi cycles through a variety of subjects on Lampedusa, capturing them in what could pass as spontaneous moments if the careful framing of the mostly static shots didn’t reveal their artificiality. We thus observe, amongst others, kids making slingshots from branches and strips of rubber gloves, a local radio DJ taking requests from callers, a scuba diver fishing for sea urchins, and the coast guard answering distress calls from boats carrying migrants, going out on rescue missions in the turbulent waters and bringing the survivors to detention centers on the island.

One of the kids, 12-year-old Samuele Pucillo, gradually emerges as the film’s protagonist. He is an effervescent, irresistible screen presence, gesticulating wildly while speaking with a thick Sicilian accent and chewing the ear off any adult who comes within reach. Samuele is an effortlessly charismatic character and Rosi clearly delights in capturing his vivacious eccentricity. It’s indeed a pleasure to watch him messily eat the spaghetti his grandmother made him, eviscerate the English language in class, and gleefully slaughter a whole cluster of cacti with his slingshot. At length, however, as Fire at Sea spends more and more time with Samuele and the migrants make but a handful of short appearances, one starts to wonder whether Rosi, who lived on Lampedusa for a year to shoot the film, didn’t fall in love with the local culture and ended up making the wrong documentary. Should we be enjoying ourselves so much while watching a documentary on one of the worst humanitarian crises of our time?

And that’s when the horror kicks in. For its final 20 minutes, Fire at Sea relocates to the middle of the Mediterranean, where the coast guard are unloading a newly arrived boat. Unconscious bodies are dragged and piled onto dinghies. Some of them are violently convulsing, on the verge of dying from dehydration. Children are crying, people are wailing. One man has been so viciously beaten that he’s unable to speak or walk by himself, his vacant face disfigured by violet bruises and bleeding gashes. A woman is in complete hysterics, screaming and compulsively pouring water over her head. Finally, the camera goes aboard the migrants’ boat and below deck — the “third class compartment,” as we’ve previously been informed — where dozens of bodies lie heaped all over the place, either killed by the heat or trampled to death.

This sequence is acutely harrowing, nigh unwatchable. A priori, any documentary that galvanizes the viewer into seriously considering the extreme horror of the migrant crisis is commendable. Yet why did Rosi feel it necessary to distract and entertain his audience before unleashing this barrage of atrocity? Did he not trust that the images were ghastly enough on their own, or did he feel his audience needed to be punished for their complacency? Most troubling of all is his exploitation of Samuele. Rosi would undoubtedly argue that he wished to depict the duality of life on Lampedusa, but that’s simply not sustainable. An adorable little boy is not representative of the island, and the other subjects are too few and get far too little screen time to add up to an illustrative portrait. Instead, Samuele emerges as a stand-in for the audience: running around and playing all day without a care in the world, content in his ignorance while a humanitarian disaster takes place right in front of his nose.

In the scene that immediately precedes the final rescue mission, Samuele is getting a check-up at the doctor’s, asking him a million questions, as is his custom. The boy turns out to be a major hypochondriac, which is hilarious upon a first watch. When, in retrospect, you consider that the silly, inconsequential worries of a 12-year-old son of a fisherman – hardly someone emblematic of first-world privilege – were set up, possibly also scripted, to first inspire your laughter and then your self-disgust, it can’t help but make one question the filmmaker who would resort to such tactics, even with the best possible intentions.

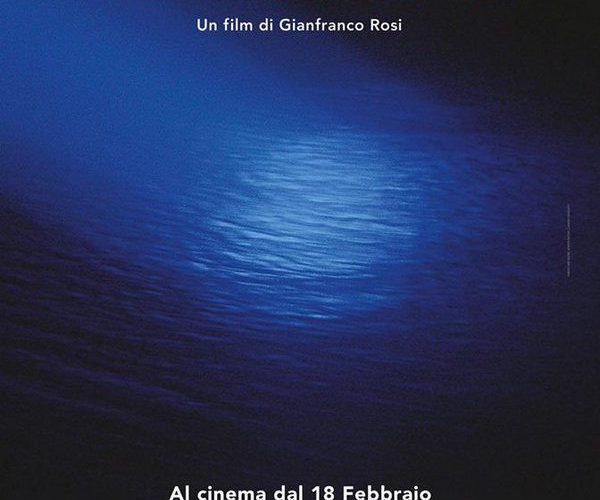

Fire at Sea premiered at the 2016 Berlin International Film Festival and opens on October 21.