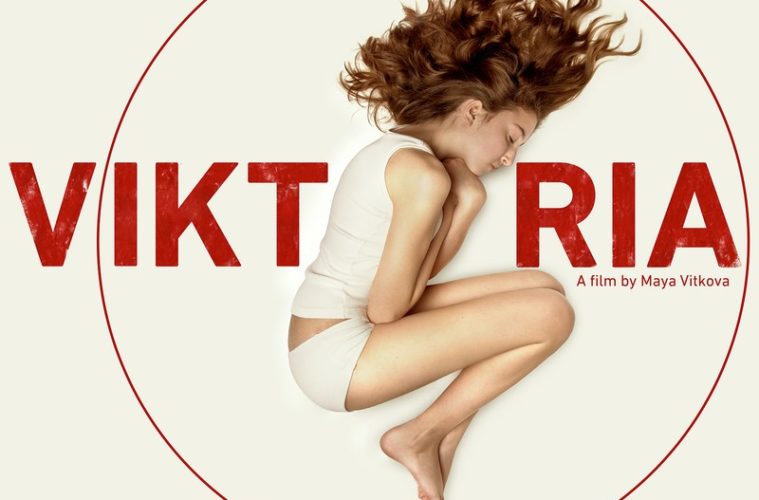

Loosely based on a stranger than fiction story of a Bulgarian baby born without a belly button and umbilical cord, the expansive Viktoria is part-political allegory, part-coming of age psychodrama, and part-graphically sensual ode to the experiences of women. Set in the decade before the impending collapse of the socialist regime and the ensuing decade after, Maya Vitkova’s debut looks at the internal effects of an oppressive environment on the lives of three generations of women.

In one of many enigmatic storytelling touches, Viktoria painstakingly marks the time periods, opening with a long sequence establishing the political status quo through archival footage, but it belies the true intentions of the movie, which are less engaged with the intimate details of these periods of government and more interested in probing how these fluid governments influence individuals on a psychological level.

For nearly the first forty five minutes, Viktoria centers only on Boryana (Irmena Chichikova), a politically engaged young woman whose hatred for Bulgaria is only surpassed by her annoyance for the baby growing in her body. Married to a government stooge and enraged with her feelings of stagnation living in the country, Boryana dreams of a time when she can escape to “Venice and beyond.”

Boryana tries over and over to sabotage the baby, smoking secret cigarettes in the bathroom, and attempting self-abortions that make the nightmarish procedures of 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days look dignified. In this period of pregnancy, the camerawork manages the tricky sensation of being in and out of Boryana’s character, bringing out the societal perception as only a breeding machine, and the intimate personal disappointment of being stuck in a country where the walls are paradoxically both crumbling and closing in.

It’s only poetic irony that the baby is a miracle of science that becomes a symbol of Bulgaria’s resilience, and one of the poster children for the regime. Sensing a PR opportunity, the Socialist party showers Boryana and her new daughter, Viktoria, with gifts like a free apartment, cushy jobs for the father, and a gilded lifestyle for years into Viktoria’s life.

Comparable to Costas-Gavras’ Z, the Socialist government is viewed with a thinly cloaked maliciousness, and cinematographer Krum Rodriguez frames these scenes of political parlor games with an antiseptic uniformity, as best exemplified in the visual joke of one half of the delivery room being filled with doctors and the other half being filled with old white men in suits as Boryana is handed Viktoria.

Moving forward a decade, the 10-year-old (Daria Vitkova) Viktoria lives in a fantasy world of gilded opportunity, to the point where random bystanders are forced to hang onto every note when she clangs together some notes at a nation-sponsored piano recital. Vitkova draws these scenes with a mordant, politically conscious humor, emphasizing the absurdity of the situations, but never letting them overwhelm the more austere context of the social commentary.

Through all these fawning events, Boryana can barely hide her casual disgust, spending formal events biding her time stringing gum around in her mouth, and coming to parties a bottle of wine in, and with a random man on her arm. Less ambitious directors may have crafted a whole movie from this contrast between a mother who has no allegiance to her country, and a daughter who treats the government like Santa Claus, but Viktoria sprawls in much more complex directions.

Cutting years and decades in single match cuts, Viktoria moves from more satirical material to biting familial drama as Boryana struggles to view her daughter as anything other than a symbol of her oppression, and an echo of a fallen age. Boryana isn’t always sympathetic in these moments, but Chichikova’s performance is such a potent blend of pain and anger that it’s never less than understandable.

Viktoria is far more than just a narrative prop – especially as the regime collapses – and she’s placed into a normal position in society. As the already sizable gulf between her mother and father widens, Viktoria is resentful that her mother treats her with such coldness, but also deeply wanting the love that she never received. This is contrasted with another emerging relationship with Boryana’s mother, Dima (Mariana Krumova), who is trying to atone for her own failed mothering.

In this last third, the movie dives into headier material as it juxtaposes philosophical discussions about raising grandchildren, epochal moments of Viktoria’s experiences as a teenager, and the contrasting purity and confusion of womanhood. But even in its frank treatment of bodily process, there’s an honoring eye to these sequences that present women in all their glory.

Whether Boryana is anguishing over her inability to provide breastmilk to her child in a scene that evokes Jane Campion, or a teenage Viktoria is straining to rub out a period stain, there’s always a keen and defining sense that Viktoria was created by a women who understands these sensations, and has deep respect for the mysticism of femininity.

Viktoria occasionally bites off more than it can handle, but even as it threatens to become unwieldy, it always feels essential. And while there’s at least three different movies in here, Vitkova wrangles this grandiose story of political upheaval into a vibrant piece of filmmaking that feels singular and overwhelming.

Viktoria opens in limited release on Friday, April 29th.