When Kathleen Hanna is shown sitting at her home discussing her exit from fronting Le Tigre, she says, “I felt I had said everything I wanted to say.” It’s the kind of sentiment that makes you truly respect an artist, knowing they weren’t in it for the money or the fame. They used their art as a platform to share their ideals and try to change an injustice in the world. And while we quickly discover this reason was in fact a lie—The Punk Singer is as much a document of her career as it is a public explanation for the truth behind her early retirement—it doesn’t negate that her songs were utilized for this purpose. A feminist with as many detractors as fans (if not more) Hanna has always been larger than her music alone.

Learning about her time at Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA as an outspoken performance artist commenting on sexual abuse and its prevalence—her own roommate was dragged by the neck in an attempted rape while Hanna was at school—before producing feminist zines and the Riot Grrl manifesto, it’s no surprise director Sini Anderson would craft her story as a sort of lo-fi visual collage of footage and ephemera in much the same way. Interspersed with all-access interviews spanning a year throughout 2010 and 2011 are fan-shot performances of Hanna’s punk rock genesis with Bikini Kill; testimonials from writers (Ann Powers), activists (Lynn Breedlove), and artists (Joan Jett, Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, and Sleater-Kinney’s Corin Tucker); and never-before-seen insight into her private life with husband Adam Horovitz of Beastie Boys fame and her struggle with illness.

Anderson includes a brief history of the feminist movement from Suffragists to the fight for equality to eventually placing Hanna and her contemporaries into its “Third Wave.” There are plenty examples of Hanna on stage enforcing her “women to the front” policy so they wouldn’t get physically destroyed by their male counterparts’ penchant for mosh pits spiraling out of control. She is also shown engaging the audience with confident rhetoric to show she wasn’t just some Valley Girl screaming without purpose. We learn the accent was intentionally cultivated, how she knowingly utilized her sexuality to get her message noticed, and how the media’s desire to sensationalize everything led her to constantly question every action; this reached the point of her asking for help that wouldn’t somehow be construed as weakness by an ignorant populace who simply don’t understand what feminism is.

I never heard of Kathleen Hanna nor heard any of her bands’ music before sitting down to watch The Punk Singer—a fact placing me in a position to declare it isn’t merely a fan-service documentary an outsider would feel alienated from enjoying. Not being a huge fan of punk music, I won’t say I necessarily enjoyed Bikini Kill’s songs on a level beyond respecting the lyrical message and mission set forth by Hanna, Tobi Vail, Kathi Wilcox, and Billy Karren. Instead, what I took from Anderson’s look at Hanna’s artistic and political journey was how interwoven she was to the Pacific Northwest scene, not only coining the phrase “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for friend Kurt Cobain but also her relationship with Sonic Youth, Beastie Boys, and the Riot Grrl movement in general.

Her solo album entitled Julie Ruin, as well as Le Tigre’s work appealed to my sensibilities more musically while also proving how powerful a voice Hanna has removed from the screaming of her Bikini Kill days. As a result, the impact she had and still has on feminism and punk shouldn’t be underestimated or overshadowed by the media blitzes pitting her against Courtney Love thanks to a badly reported fight years ago or the false truths about her past she would never have signed off on for mass consumption. Her decision to practice a full media blackout as protest to their intrusiveness only makes you respect her more and realize how true her motivations were from the very beginning. Hopefully her present-day return as singer for The Julie Ruin will once again impact women on a global level.

As a non-fan, this insight into her evolution is what I latched onto. For stalwart supporters, however, I’m guessing the revelation of her illness during her hiatus will be the biggest draw. Anderson’s handling of this reveal was a bit overwrought for me—enough so I thought I’d found out Hanna had died. But I do understand its importance insofar as giving those who care so much a look into what had thus far been a veiled personal life. The film stays true to her humanity by heeding her request to not have too many male interviewees “legitimizing” what the women involved were already saying and it fearlessly shows how little she cares about what anyone thinks of her. Hanna has always carved her own path while enduring many hardships along the way. And she’s inspirationally still standing tall.

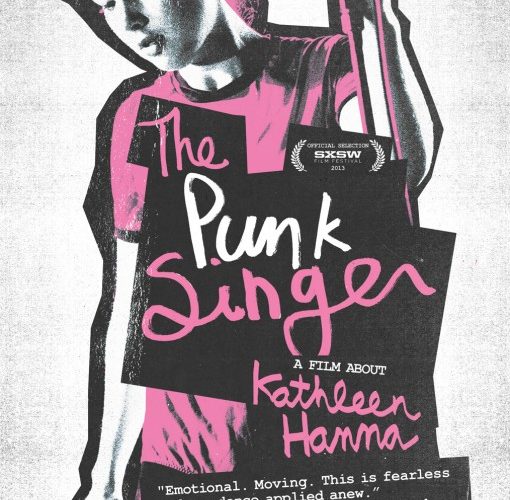

The Punk Singer opens in limited release on Friday, November 29th.